Sunrise Food Infrastructure Initiative: Local Markets Viability Project

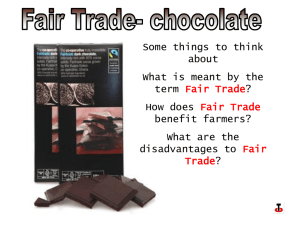

advertisement