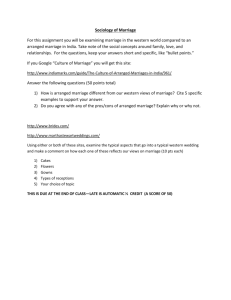

forced marriage and asylum: perceiving the

advertisement