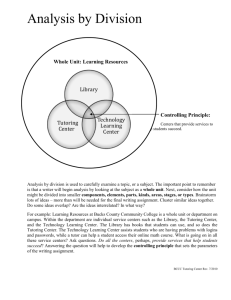

as a PDF

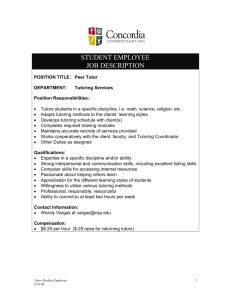

advertisement