Plenty of options for LNG

advertisement

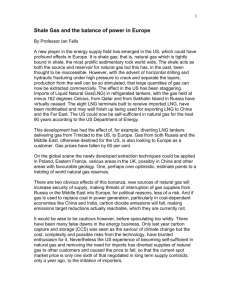

Special report: Finance Plenty of options for LNG As the US is poised to become a major gas exporter, operators are seeing a broader range of finance options, writes Inosi Nyatta* L IQUEFIED natural gas (LNG) export projects made up a significant portion of project finance activity in 2014, including a number of large projects in North America. This reflects a trend in the growing prominence of LNG export projects, particularly post-financial crisis. Due to the high capital requirements of these projects, those that have closed debt financings have generally sourced the debt from multiple and varied financing sources. This includes recent US LNG financings, which have incurred debt from commercial bank, bond and export credit agency (ECA) lenders. Cameron LNG and other US projects illustrate some of the developing themes in LNG export project financing. Table 1 illustrates the significant capital costs of LNG export projects. Table 1: capital costs of LNG export projects Project Freeport Cameron Sabine Pass (initial financing) Ichthys Australia-Pacific LNG (liquefaction project) PNG LNG (initial financing) Financial Close Nov 2014 Oct 2014 May 2013 Jan 2013 Sep 2012 Mar 2010 Total Cost No. of Trains $10.9 billion 2 $10.9 billion 3 $7.9 billion 4 $34 billion 2 $12.9 billion 2 $18.2 billion Source: Infrastructure Journal The surge in shale-gas production in the US has led to increased gas availability and the possibility of LNG exports from the US, based on Henry Hub pricing. As a result, US LNG export project development began primarily with conversion of gas import terminals to LNG export terminals (eg Cameron, Sabine Pass, Freeport, Cove Point), but greenfield developments have begun as well (eg Jordan Cove, Corpus Christi). The rapid development in the US of LNG projects, starting with the conversion of import terminals and the rapidly planned expansions of these projects and the development of new greenfield projects, is putting the US at the forefront of the LNG export industry. More than 40% of worldwide proposed pre-final investment decision (FID) liquefaction capacity is in the US, according to the International Gas Union’s 2014 World LNG Report, though “[r]egulatory obstacles, combined with potential Henry Hub volatility and the limits of global LNG demand, will likely contain the number of projects coming online through the end of the decade”. The prominence of US LNG projects and their pricing based on Henry Hub rather than the more traditional oil-linked indices has opened up a new pricing paradigm for LNG. The impact of this development creates growing competition based on more flexible LNG pricing, which may be driven in large part by the export terminal location in or outside the US or the ability of sellers to source gas using a portfolio approach. The significant capital needs of LNG projects have required sponsors to tap multiple sources of third party financing to fund construction. Export credit agencies have traditionally played and continue to play a leading 42 April 2015 2 role in large project financings, with commercial banks also being key sources of financing liquidity, particularly during the construction phase of these projects. However, experience has shown that commercial banks can be subject to capacity constraints, especially for projects in countries with higher real or perceived political/ country risk, and market volatility, as was the case in and for a while after the 2008 financial crisis. With the rise in US projects has come a renewed attention on project bonds, which were first used in connection with the Qatari LNG projects starting in the mid-1990s. The depth of US debt markets, particularly for US issuers, has created attractive opportunities for the refinancing of initial bank debt. This has enabled a couple of US projects to use a “mini-perm” structure even for LNG projects with capital expenditure needs well into the multibillion dollar range. The Sabine Pass project, for example, has already terminated over $2 billion of the $5.9 billion credit facilities the project entered into in May 2013 through successive note offerings. For non-US markets, however, the availability of project bonds may remain more constrained; these are subject to general emerging market risk and political/country risk appetite. In emerging markets, project bonds would likely be more generally available for refinancing projects that are complete or in countries that are investment grade (or near investment grade) that have a positive track record in international debt markets. Traditionally, LNG export projects (which were historically outside the US) were financed with long tenor debt, typically over 15 to 16 years. This long tenor debt is mostly available from ECAs, paired with commercial bank project finance loans and/or project bonds. The Qatari LNG project bonds issued in 1996, for example, had tenors of 10 and 20 years. US projects, however, have access to the “mini-perm” market (that is, loans with tenor closer to five to 10 years), which is supported by the depth and strength of the US debt capital markets for US issuers as a mitigant to refinancing risk. For projects with significant capital requirements such as LNG export projects, it seems unlikely that the miniperm structure will extend outside of the US, particularly to emerging markets. This is partly because these projects are more likely to require a significant component of ECA debt, and the ECAs’ more conservative approach to refinancing risk limits the ability of ECA-financed projects using a mini-perm structure (although recent reports indicate that JBIC may be willing to consider “soft” miniperms, which, instead of requiring repayment after the seven to 10 year period, merely go up in cost for the remainder of the loan, for certain types of projects in certain regions). Even if the availability of mini-perms outside of the US expands, the greater uncertainty surrounding the ability to refinance projects in emerging markets during the life of the project may constrain their utilisation. Conversely, the financing obtained by the Cameron project illustrates that strong US projects can also access longer tenor debt, including from commercial banks. Because of the growth in LNG projects globally, many projects are in jurisdictions with new or changing www.petroleum-economist.com Special report: Finance regulatory regimes. For instance, the processes for obtaining authorisation from the US Department of Energy (DOE) under the Natural Gas Act for export of natural gas from the US to non-free trade agreement (FTA) countries was virtually untested until 2010 and continues to attract attention from lenders concerned with regulatory and perceived political risk in connection with the issuance and maintenance of export authorisations. A similar process of familiarisation is under way with respect to the projects being proposed and in development in Canada, and the interplay between the US and Canadian regulatory regimes in projects located near the border may complicate this further. The recent dramatic changes to the regulatory landscape of Mexico’s energy sector are still being processed and will affect any projects there; similarly, new regulations dealing with oil and gas in East Africa will need to be evaluated closely. Understanding and getting equity investors and lenders comfortable with the applicable regulatory regime will continue to be a key part of any successful project development and financing. The LNG market now includes projects that utilise a tolling offtake arrangement instead of the traditional integrated buy-sell project model. Cameron was the first LNG export project to adopt a true tolling structure; Freeport has subsequently adopted a tolling structure. The tolling model turns a number of project risks into tolling customer credit risk, so the credit story of tolling customers and the terms of the tolling agreement become crucial in projects that elect to use tolling. In particular, lenders will tend to focus on any exceptions to “toll or pay” requirements in the tolling agreement and generally require detailed diligence and advice in order to get comfortable that any risks not being borne by the tolling customer are acceptable. Furthermore, even for projects that use a tolling model, lenders and rating agencies may still require some limited visibility into the project’s offtake strategy and arrangements – ECAs often are particularly focused on this issue in the context of import financing. In the US alone, 31 applications for export of about 27.9 billion cubic feet per day (cf/d) of LNG to non-FTA countries are currently under review at the DOE, while nine applications (for about 10.6 billion cf/d) have already been finally or conditionally approved. Although it remains unclear on what timetable the pending and subsequent *Inosi Nyatta, a partner in Sullivan & Cromwell LLP’s project development and finance group, who has advised on a number of successful LNG projects within and outside the US, assisted by Alex Stein, an associate at Sullivan & Cromwell LLP Figure 1: Proportion of initial financing by ECAS (% of total non-sponsor debt financing) US$billion 18 Active ECAs 16 China Exim COFACE EDC EFIC JBIC KEXIM 14 12 10 70% 8 66% 6 KfW K-SURE NEXI SACE US Exim 81% 58% 4 46% 25% 2 0 Ichthys APLNG PNG LNG Cameron ECA direct and covered tranches Source: Infrastructure Journal www.petroleum-economist.com Sabine Pass Freeport Other non-sponsor debt financing applications will receive authorisations from the DOE, new projects are adding themselves to the queue frequently. Significant additional projects globally in markets with new gas discoveries, including Mozambique and Tanzania, and the changes to Mexico’s energy regulatory regime could encourage LNG export projects there as well. In addition to any potential impact on LNG prices that this growth could create, LNG projects could start to run up against capacity limits on the part of lenders, operators and contractors. Commercial banks and other institutional lenders could start to face sector or country constraints on the quantum they can lend to any given sector and/or country. Furthermore, the rapid growth in the number of projects could result in significant competition for contractors and operators with sufficient expertise to build and operate their projects. These trends, if continued, could lead to both higher costs of financing, construction and operations. The recent drop in oil prices may cause some projects that were counting on high oil-linked LNG prices to reconsider their feasibility. Furthermore, low oil prices may impact LNG marketing, as LNG buyers take more time to analyse projects with oil-linked as opposed to Henry Hub linked prices. More competition can be expected to continue between the two pricing models. To the extent that there is a strong supply of LNG from projects benefiting from low natural gas prices, a number of potential LNG export projects currently in the pipeline may be reconsidered completely. Given the various challenges facing LNG projects, support from the project sponsors – both in terms of expertise and management – remains crucial for any project to succeed. Multiple sponsors can clearly strengthen the project’s credit and access to financial and other resources, but it is equally important that sponsors are aligned in their commercial objectives for the project as complex negotiations ensue regarding construction, operation, sourcing, sales and financing arrangements. As with other projects, more simple contractual and commercial arrangements in LNG projects ease the path to the development and financing the project. However, as the scope of potential LNG projects grows, including based on conventional gas, unconventional gas and gas purchased from the grid, more novel approaches and structures are likely to develop to optimise operational efficiencies, commercial objectives and economies of scale, including sharing of facilities and pooling of operations across differently owned facilities. These more complex structures can also be financeable if they are appropriately structured in a manner that enables lenders, equity holders and other project participants to understand the risk allocation embedded in these arrangements. This enables project participants to adequately understand and mitigate these risks. Efficient and timely development of an LNG export project requires that multiple teams work together and coordinate on tasks that require vastly different areas of expertise. At the same time that financing documents are being drafted and negotiated, commercial arrangements with engineering, procurement and construction contractors, LNG buyers and tolling customers may be being finalised and regulatory applications prepared, processed and evaluated. As many of these commercial, regulatory and financing workstreams will develop in parallel, successfully financed projects are generally based on efficiently organized and coordinated teams of sponsors and advisors working together to meet required deadlines and targets.• April 2015 43