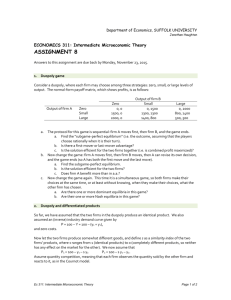

chapter 7

advertisement