Licensed to: iChapters User

Licensed to: iChapters User

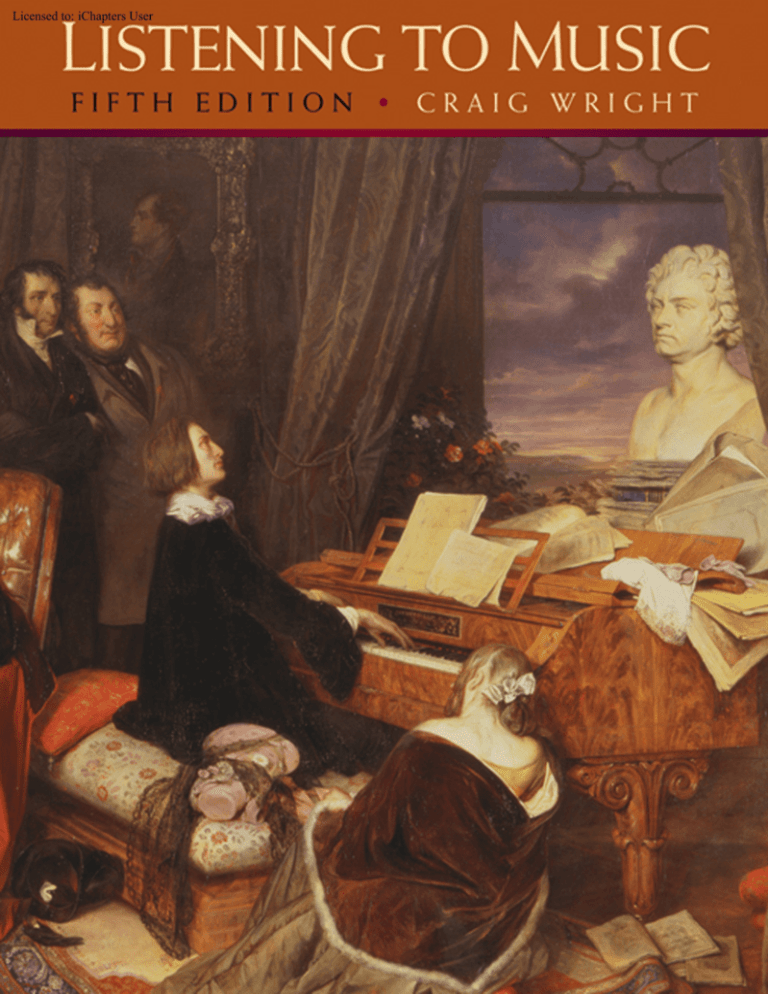

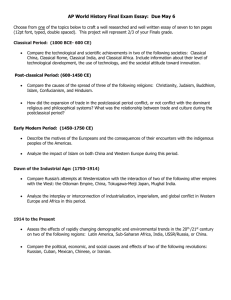

Listening to Music, Fifth Edition

Craig Wright

Publisher: Clark Baxter

Senior Development Editor: Sue Gleason

Assistant Editor: Emily A. Ryan

Editorial Assistant: Nell Pepper

Technology Project Manager: Rachel Bairstow

Executive Marketing Manager: Diane Wenckebach

Marketing Assistant: Marla Nasser

Project Manager, Editorial Production: Trudy Brown

Creative Director: Rob Hugel

Art Director: Maria Epes

Print Buyer: Judy Inouye

Permissions Editor: Roberta Broyer

Production Service: Melanie Field

Text and Cover Designer: Diane Beasley

Photo Researcher: Stephen Forsling

Copy Editor: Tom Briggs

Cover Image: Josef Danhauser (1805–1845). Franz Liszt at the Piano. 1840.

Oil on canvas, 119 167 cm. Photo: Juergen Liepe. Nationalgalerie,

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Bildarchiv Preussischer

Kulturbesitz / Art Resource, NY.

Compositor: Thompson Type

Text and Cover Printer: Courier Corporation/Kendallville

© 2008, 2004 Thomson Schirmer, a part of The Thomson Corporation.

Thomson, the Star logo, and Schirmer are trademarks used herein under

license.

Thomson Higher Education

10 Davis Drive

Belmont, CA 94002-3098

USA

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—

graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording,

taping, Web distribution, information storage and retrieval systems, or in

any other manner—without the written permission of the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 11 10 09 08 07

Library of Congress Control Number: 2006906782

For more information about our products, contact us at:

Thomson Learning Academic Resource Center

1-800-423-0563

For permission to use material from this text or product,

submit a request online at

http://www.thomsonrights.com.

Any additional questions about permissions can be

submitted by e-mail to

thomsonrights@thomson.com.

ISBN-13: 978-0-495-18973-2

ISBN-10: 0-495-18973-1

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Licensed to: iChapters User

Chapter

1

Listening to Music

“It is perhaps in music that the dignity of art is most eminently apparent, for it

elevates and ennobles everything that it expresses.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832)

“It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing.”

Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899–1974)

W

e listen to music because it gives us pleasure. But why does it give us

pleasure? Because it affects our minds and bodies, albeit in ways that we do

not yet fully understand. Music has the power to intensify and deepen our

feelings, to calm our jangled nerves, to make us sad or cheerful, to inspire us

to dance, and even, perhaps, to incite us to march proudly off to war. Since

time immemorial, people around the world have made music an indispensable part of their lives. Music adds to the solemnity of ceremonies, arts, and

entertainments, heightening the emotional experience of onlookers and participants. If you doubt this, try watching a movie without listening to the musical score, or imagine how empty a parade, a wedding, or a funeral would be

without music.

HOW MUSICAL SOUND AND

SOUND MACHINES WORK

When we listen to music, we are reacting physically to an organized disturbance in our environment. A voice or an instrument creates a vibration that

travels through the air as sound waves, reaching our ears to be

processed by our brain as electrochemical impulses (see boxed

essay). Low-pitched sounds vibrate slowly and move through

the air in long sound waves; higher pitches vibrate more rapidly

and move as shorter waves.

While these principles of acoustics are invariable, our means

for capturing and preserving sound have evolved over the centuries, with an ever-accelerating rate of change. Most early

musical traditions were passed down by oral means alone. Not

until around 900 C.E., when Benedictine monks began to set

notes down on parchment to preserve their chants (Fig. 1–1),

was a significant amount of music preserved in written notation. Thus, at first, only religious music was written down.

Popular music—dances and troubadour songs, for example—

first appeared in notation around 1250. As the centuries progressed, composers began to insert such directions as “dynamics” (indicating louds and softs) and “tempo” markings (showing

how fast the piece should go), eventually producing the complex musical score familiar to classical musicians today.

Machines for capturing and replaying sound began to appear in the nineteenth century, with Thomas Edison’s phonoStiftsbibliothek, St. Gallen

F I G U R E 1–1

A medieval representation of how music

was transmitted. Pope Gregory the Great

(590–604) receives what is now called

“Gregorian chant” from the Holy Spirit

(a dove on his shoulder) and communicates

it orally to a scribe who writes down the

music on either parchment or a wax tablet.

2

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Licensed to: iChapters User

Listening to Music

■

C H A P T E R

1

3

Music and the Brain

© Nir Elias/Reuters/Corbis

M

ozart had an extraordinary musical ear—or,

more correctly, musical brain. In April 1771, at

the age of fourteen, he heard Gregorio Allegri’s

Miserere, a two-minute religious work, performed in Rome,

and later that day wrote it down in all parts by memory,

note for note, after just this one hearing. Obviously, he

could process and retain far more musical information

than can the rest of us. Mozart had a very keen sense of

absolute pitch (the ability to instantly recognize specific

pitches), a gift given to only one in about 10,000 individuals. But how, in simple terms, do we hear and remember music?

When a musician, such as virtuoso Sarah Chang, sings

or plays an instrument, she creates mechanical energy

that moves through the air as sound waves. These first

reach the inner ear where the cochleae (one for each ear)

Sarah Chang playing the violin.

Image not available due to copyright restrictions

convert sound energy into electrical signals. These are

then passed by means of neurons to the primary auditory cortex, located in the center of the brain, where the

neurons are “mapped” in a way that identifies the pitch,

color, and intensity of sound. How we feel about the

music we hear—happy or sad, energetic or melancholy—

is determined by different areas in this and other parts of

the brain. Neurobiologists have observed increased levels of the chemical dopamine in our gray matter when

pleasing music is heard, just as when we enjoy such experiences as eating chocolate. Thus, sound patterns

enter our brain and incite specific neurological reactions

that can make us feel relaxed or agitated, happy or sad.

Oddly then, music alters the way we feel in much the

same manner as a chemical substance, such as a candy

bar, a medicine, or a drug. We can acquire the mechanism for a “mood-enhancing” experience, it seems, either over the counter or over the airwaves.

graph, patented in 1877, representing the most significant development. The

twentieth century saw the advent of the magnetic tape recorder (first used to

record music in 1936). In the 1990s, these earlier devices were superseded by

the digital technologies of the compact disc (CD) and the MP3 file. In these

formats, the pitch, intensity, and duration of any sound are converted into

numerical data that can be stored on disc, hard drive, or any number of other

digital media. When a digital recording is played, these numerical data are reconverted into electrical impulses that are amplified and pushed through

audio speakers or headphones as sound waves (Fig. 1–2).

technology of recorded music

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Licensed to: iChapters User

4

P A R T

I

■

The Elements of Music

© PictureNet/Corbis

LISTENING TO WHOSE MUSIC?

F I G U R E 1–2

A student listening to an MP3 file on

an iPod.

Music is heard everywhere in the world. Numerous forms of art music, rooted

in centuries of tradition, thrive in China, India, Indonesia, and elsewhere. Musical practices associated with religious ceremonies, coming-of-age rituals, and

other social occasions flourish across Africa and Latin America. Dance music

serves a central function for youth culture in nightclubs and discotheques

across the globe. In the West, classical music still holds sway in concert halls

and opera houses, while numerous idioms of Western popular music—rock,

hip-hop, and country, for example—dominate the commercial landscape.

Jazz, a particularly American form of vernacular music, shares traits with both

Western classical and popular music.

What is more, the increasing frequency of “fusions” among musical styles

illustrates the trend of musical “globalization” in recent years. Afro-Cuban

genres draw upon musical traditions ranging from Caribbean styles, to jazz,

to the music of old Spain. Classical cellist Yo-Yo Ma performs with traditional

Chinese musicians on the Silk Road Project, while British pop singer Sting has

collaborated with musicians ranging from jazz virtuoso Branford Marsalis to

Algerian singer Cheb Mami. To be sure, there are plenty of styles, and fusions

of styles, from which to choose. We might on occasion choose a certain kind

of music—classical, traditional, or popular—according to its association with

our own heritage, while at other times we might base our decision on our

mood or activity at a particular moment.

CLASSICAL MUSIC–POPULAR MUSIC

What is a “classic”?

Most of the music that will be discussed in this book is what we generally refer

to as “classical” music. We might also call it “high art” music or “learned” music,

because a particular set of skills is needed to perform and appreciate it. Classical

music is often regarded as “old” music, written by “dead white men.” But this is

not entirely accurate: no small amount of it has been written by women, and

many “high art” composers, of both sexes, are very much alive and well today.

In truth, however, much of what we hear by way of classical music—the music

of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, for example—is old. That is why, in part, it

is called “classical.” We refer to clothes, furniture, and automobiles as “classics”

because they have timeless qualities of expression, proportion, and balance.

So, too, we give the name “classical” to music with these same qualities, music

that has endured the test of time.

Popular music, as its name suggests, appeals to a much larger segment of

the population. Pop and rock CDs outsell classical music recordings by more

than ten to one. Popular music can be just as artful and just as serious as classical music, and often the musicians who perform it are just as skilled as classical

musicians. Some musicians are equally at home in both idioms (Fig. 1–3). But

how do classical and popular music differ?

• Classical music relies on acoustic instruments (the sounds of which are

not electronically altered), such as the trumpet, violin, and piano; popular

music often uses technological innovations such as electrically amplified

guitars and basses, electronic synthesizers, and computers.

• Classical music relies greatly on preset musical notation, and therefore the

work (a symphony, for example) is to some extent a “fixed entity;” popular

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Licensed to: iChapters User

•

•

•

•

music relies mostly on oral and aural transmission, and the work can change

greatly from one performance to the next. Rarely do we see performers reading from written music at a pop concert.

Classical music is primarily, but by no means exclusively, instrumental, with

meaning communicated through a language of musical sounds and gestures;

most popular music makes use of a text or “lyric” to convey its meaning.

Classical compositions can be lengthy and involve a variety of moods, and

the listener must concentrate over a long period of time; most popular pieces

are relatively short, averaging from three to four minutes in length, and possess a single mood from beginning to end.

In classical music the rhythmic “beat” often rests beneath the surface of the

music; popular music relies greatly on an immediately audible, recurrent

beat.

Classical music suggests to the listener a chance to escape from the everyday world into a realm of abstract sound patterning; popular music has a

more immediate impact, and its lyrics often embrace issues of contemporary life.

Why Listen to Classical Music?

Given the immediate appeal of popular music, why would anyone choose to

listen to classical music? To find out, National Public Radio in 2004 commissioned a survey of regular listeners of classical music. Summarized briefly

below, in order of importance, are the most common reasons expressed by

classical listeners:

1. Classical music relieves stress and helps the listener to relax.

2. Classical music helps “center the mind,” allowing the listener to concentrate.

3. Classical music provides a vision of a better world, a refuge of beauty and

majesty in which we pass beyond the limits of our material existence.

4. Classical music offers the opportunity to learn: about music, about history,

and about people.

■

C H A P T E R

1

5

© Lynn Goldsmith/Corbis

Listening to Music

F I G U R E 1–3

Trumpeter Wynton Marsalis can record a

Baroque trumpet concerto one week and

an album of New Orleans–style jazz the

next. He has won nine Grammy awards,

seven for various jazz categories and two

for classical discs.

Classical listeners were given the chance to elaborate on why they prefer

this kind of music. Here is just one typical response for each category:

1. “My work is pretty stressful, and when it gets really stressful, I turn to classical. It calms me down. It soothes the savage beast.”

2. “It’s very good for the brain.”

3. “Enjoying a symphony takes me back to great childhood memories.”

4. “I’m not educated in music. I’m like really stupid about it, but this is one way

[listening on the radio] that I can educate myself, in my own stumbling,

bumbling musical way.”

classical music good for the brain

From mental and emotional well-being, to increased concentration and enriched imagination, to deeper understanding of human culture and history, it

would seem that classical music has something to offer virtually everyone.

Classical Music All Around You

You may not listen to classical music on the radio (found on the dial in most

regions between 90.0 and 93.0 FM). You may not attend concerts of classical

music. Nevertheless, you listen to a great deal of classical music. Vivaldi con-

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Licensed to: iChapters User

6

P A R T

I

■

The Elements of Music

everyday use of classical music

certos and Mozart symphonies are played regularly in Starbucks. Snippets of

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony introduce segments of the news on MSNBC.

Traditional operatic melodies provide runway music as models strut in telethons for Victoria’s Secret clothing, and a famous Puccini aria sounds prominently in the best-selling video game Grand Theft Auto, perhaps for ironic effect. What famous composer has not had one or more of his best-known works

incorporated into a film score, to heighten our emotional response to what

we see? Classical music—composed by Bach, Beethoven, Copland, Verdi, and

especially Mozart, among others—has also been appropriated to provide sonic

backdrops for radio and television advertisements. Here it usually acts as a

“high end” marketing tool designed to encourage rich living: to sell a Lexis automobile or a De Beers diamond, advertisers realize, they must allow Mozart,

not Kurt Cobain or Eminem, to set the mood.

Attending a Classical Concert

aspects of a classical concert

© Corbis

F I G U R E 1–4

Symphony Hall in Boston. The best seats

for hearing the music are not up front, but

at the back in the middle of the balcony.

There is no better way to experience the splendor of classical music than to

attend a concert. Compared to pop or rock concerts, performances of classical music may seem strange indeed. First of all, people dress “up,” not “down”:

at classical events, attendees wear “costumes” or “uniforms” (coat and tie, suit,

or evening wear) of a very different sort than they do at, say, rock concerts

(punk, grunge, or metal attire). Throughout the performance, the classical audience sits rigidly, saying nothing to friends or performers. No one sways, dances,

or sings along to the music. Only at the end of each composition does the audience express itself, clapping respectfully.

But classical concerts weren’t always so formal. In the eighteenth century,

the audience talked during performances and yelled words of encouragement

to the players. People clapped at the end of each movement of a symphony

and often in the middle of the movement as well. After an exceptionally pleasing performance, listeners would demand that the piece be repeated immediately (an encore). If, on the other hand, the audience didn’t like what it heard,

it would express its displeasure by throwing fruit and other debris toward the

stage. Our modern, more dignified classical concert was a creation of the nineteenth century (see page 254), when the

musical composition came to be considered a work of high art worthy of reverential silence.

Attending a classical concert requires

preparation and forethought. Most important, you must become familiar in advance with the musical repertoire. Go to

a music library and listen to a recording

of the piece that will be performed, or perhaps download it from iTunes. Hearing a

recording by professional performers will

prepare you to judge the merits of a live

(perhaps student) performance.

Choosing the right seat is also important. What is best for seeing may not be

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Licensed to: iChapters User

Listening to Music

best for hearing. In some concert halls, the sound sails immediately over the

front seats and settles at the back (Fig. 1–4). Often the optimal seat in terms

of acoustics is at the back of the hall, in the first balcony. Sitting closer, of

course, allows you to watch the performers on stage. If you attend a concert

of a symphony orchestra, follow the gestures that the conductor makes to the

various soloists and sections of the orchestra; like a circus ringmaster, he or

she turns directly to the soloist of a given moment. The conductor conveys

to the players the essential lines and themes of the music, and they in turn communicate these to the audience.

■

C H A P T E R

1

7

where to sit

LEARNING TO BE A GOOD LISTENER

Most people would scoff at the idea that they need to learn how to listen to

music. We think that because we can hear well, we are good listeners. But the

ability to listen to music—classical music in particular—is an acquired skill

that demands good instruction and much practice. Music can be difficult stuff.

First of all, we must learn how it works. For example, how do melodies unfold? What constitutes a rhythm and what makes a beat? And how and why

do harmonies change? Similarly, we must work to improve our musical memory. Music is an art that unfolds while passing through time; to make sense of

what we hear now, we have to remember what we heard before. Finally, we will

need to gain an understanding of the secret signs or codes by which composers

have traditionally expressed meaning in music: the tensions, anxieties, and

hostilities expressed in musical language, as well as its triumphs and moments

of inner peace. To accomplish this, we must devote our complete attention to

the music—using it as a mere backdrop to other activities simply won’t do.

We must concentrate fully in order to hear the mechanics of music at the surface level (the workings of rhythm, melody, and harmony, for example), as

well as to understand the deeper, emotional meaning. The following discussions and their accompanying Listening Exercises will begin to transform you

into disciplined and discerning listeners. At the same time, you will come to see

that classical music—indeed all music—sometimes works its magic in mysterious and inexplicable ways.

learn how music works

focus solely on the music

GETTING STARTED:

THREE MUSICAL BEGINNINGS

In a work of art that unfolds over time—a poem, a novel, a symphony, or a

film, for example—the beginning is critical to the success of the work. The

artist must capture the attention of the reader, listener, or viewer by means of

some kind of new approach as well as convey the essence of the experience

that is to follow. We can learn much about how classical music works by engaging just the beginnings of three strikingly original compositions.

Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 5

(1808)—Opening

The beginning of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 is perhaps the best-known

moment in all of classical music. Its “short-short-short-long” gesture is as much

an icon of Western culture as is the “To be, or not to be” soliloquy in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Beethoven wrote this symphony in 1808 when he was thirty-

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Licensed to: iChapters User

P A R T

I

■

The Elements of Music

Snark, Art Resource, NY

8

F I G U R E 1–5

A portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven painted

in 1818–1819 by Ferdinand Schimon

(1797–1852).

a fateful musical journey

seven and almost totally deaf (Fig. 1–5; see Chapter 21 for a biography of

Beethoven). How could a deaf person write a symphony? Simply said, he could

do so because musicians hear with “an inner ear,” meaning that their brains can

create and rework melodies without recourse to externally audible sound. In

this way, the nearly-deaf Beethoven fashioned an entire thirty-minute symphony.

A symphony is a genre, or type, of music for orchestra, divided into several

pieces called movements, each possessing its own tempo and mood. A typical classical symphony will have four movements with the respective tempos

of fast, slow, moderate, and fast. A symphony is played by an orchestra, a

large ensemble of acoustic instruments such as violins, trumpets, and flutes.

Although an orchestra might play a concerto, an overture, or a dance suite,

historically it has played more symphonies than anything else, and for that

reason is called a symphony orchestra. The orchestra for which Beethoven

composed his fifth symphony was made up of about sixty players, including

string, wind, and percussion instruments.

Beethoven begins his symphony with the musical equivalent of a punch in

the nose. The four-pitch rhythm “short-short-short-long” is quick and abrupt.

It is all the more unsettling because the music has no clear-cut beat or grounding harmony to support it. Our reaction is one of surprise, perhaps bewilderment, perhaps even fear. The brevity of the opening rhythm is typical of what

we call a musical motive, a short, distinctive musical figure that can stand by

itself. In the course of this symphony, Beethoven will repeat and reshape this

opening motive, making it serve as the unifying thread of the entire symphony.

Having shaken, even staggered, the listener with this opening blow, Beethoven then begins to bring clarity and direction to his music. The motive

sounds in rapid succession, rising stepwise in pitch, and the volume progressively increases. When the volume of sound increases in music—gets louder—

we have a crescendo, and conversely, when it decreases, a diminuendo. Beethoven uses the crescendo here to suggest a continuous progression—he is

taking us from point A to point B. Suddenly the music stops: we have arrived.

A French horn (a brass instrument; see page 51) then blasts forth, as if to say,

“And now for something new.” Indeed, new material follows: a beautiful flowing melody played first by the strings and then by the winds. Its lyrical motion serves as a welcome contrast to the almost rude opening motive. Soon

the motive reasserts itself, but is gradually transformed into a melodic pattern

that sounds more heroic than threatening, and with this, Beethoven ends his

opening section.

In sum, in the opening of Symphony No. 5, Beethoven shows us that his

musical world includes many different feelings and states of mind, among

them the fearful, the lyrical, and the heroic. When asked what the opening

motive of the symphony meant, Beethoven is reported to have said, “There

fate knocks at the door.” In the course of the four movements of this symphony (all of which are included in the six-CD set), Beethoven takes us on a

fateful journey that includes moments of fear, despair, and, ultimately, triumph.

Turn now to this opening section (Intro /1) and to the Listening Guide. Here

you will see musical notation representing the principal musical events. This

notation may seem alien to you, but don’t panic—the essentials of musical

notation will be explained fully in Chapters 2–3. For the moment, simply

play the music and follow along according to the minute and second counter

on your player.

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Licensed to: iChapters User

Listening to Music

Listening Guide

0:00

0:22

0:42

0:45

1:04

1:14

1

■

1

C H A P T E R

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 5 in C minor (1808)

First movement, Allegro con brio (fast with gusto)

Opening “short-short-short long” motive

Music gathers momentum and moves forward in

purposeful fashion

Pause; French horn solo

New lyrical melody sounds forth in strings and

is then answered by winds

Rhythm of opening motive returns

Opening motive reshaped into more heroic-sounding

melody

9

Intro

1

U

b

& b b 24 ‰ œ œ œ ˙

ƒ

b

&b b ‰ œ œ œ ˙

ß

ƒ

œ œ œ

&

bbb

˙

ß

œ œ œ œ

J

˙

ß

œ

J œ œ œ

˙

œ

J

Use a downloadable, cross-platform animated Active Listening Guide, available

at www.thomsonedu.com/music/wright.

Peter Tchaikovsky,

Piano Concerto No. 1 (1875)—Opening

All of us have heard the charming and often exciting music of Peter Tchaikovsky (1840–1893), especially his ballet The Nutcracker, a perennial holiday

favorite. Tchaikovsky was a Russian composer who earned his living first as a

teacher of music at the Moscow Conservatory and then, later in life, as an independent composer who traveled widely around Europe and even to the

United States (see Chapter 30 for his biography). All types of classical music

flowed from his pen, including ballets, operas, overtures, symphonies, and

concertos.

A concerto is a genre of music in which an instrumental soloist plays with,

and sometimes against, a full orchestra. Thus the concerto suggests both cooperation and competition, one between soloist and orchestra in the spirit of

“anything you can do, I can do better.” Most concertos consist of three movements, usually with tempos of fast, slow, and fast. Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 was composed in 1875 and premiered that year, not in Russia but

in Boston, where it was performed by the Boston Symphony. Since that time,

Tchaikovsky’s first concerto has gone on to become what The New York Times

called his “all-time most popular score.”

The popularity of this work stems in large measure from the opening section of the first movement. Tchaikovsky, like Beethoven above, begins with a

four-note motive, but here the pitches move downward in equal durations

and are played by brass instruments, not strings. The opening motive quickly

yields to a succession of block-like sounds called chords. A chord in music is

simply the simultaneous sounding of two or more pitches. Here the chords

are played first by the orchestra and then by the piano. Suddenly the violins

enter with a sweeping melody that builds progressively in length and grandeur,

a melody surely found near the top of every music lover’s list of “fifty great

a Russian concerto premiered in Boston

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Licensed to: iChapters User

10

P A R T

I

■

The Elements of Music

the essence of musical romanticism

classical melodies.” Tchaikovsky’s beginning makes clear the difference between a motive and a melody: the former is a short unit, like a musical cell or

building block, while the latter is longer and more tuneful and song-like. As

the violins introduce the melody, the piano plays chords against it. Soon, however, the roles are reversed: the piano plays the melody, embellishing it along

the way, while the strings of the orchestra provide the accompanying chords.

To make the music lighter, Tchaikovsky instructs the strings to play the chords

pizzicato, a technique in which the performers pluck the strings of their instruments with their fingers rather than bowing them. Then, after some technical razzle-dazzle provided by the pianist, the melody sweeps back one last

time. In this glorious, lush final statement of the melody by the strings, we experience the essence of musical romanticism.

Listening Guide

0:00

0:07

0:15

0:56

1:21

2:10

2:26

3:05

2

Peter Tchaikovsky

Piano Concerto No. 1 (1875)

First movement, Allegro non troppo e molto maestoso (not too fast

and with much majesty)

Intro

2

Four-note motive played by brass instruments

Chords played first by orchestra and then piano

Melody enters in violins and piano plays

accompanying chords

Piano embellishes melody; strings play

accompanying chords pizzicato

Orchestra withdraws; solo piano provides increasingly flashy technical display

Orchestra reenters with pizzicato playing

Strings play melody “with much majesty”; piano accompanies with more frequent chords

Reminiscences of melody used to create fade-out

Use a downloadable, cross-platform animated Active Listening Guide, available

at www.thomsonedu.com/music/wright.

Richard Strauss, Also Sprach Zarathustra

(Thus Spoke Zarathustra; 1896)—Opening

music inspired by a novel

There were two important composers named Strauss in the history of music.

One, Johann Strauss, Jr. (1825–1899), was Austrian and is known as “the Waltz

King” because he wrote mainly popular waltzes. The other, Richard Strauss

(1864–1949), was German and composed primarily operas and large-scale

compositions for orchestra called tone poems. A tone poem (also called a

symphonic poem) is a one-movement work for orchestra that tries to capture

in music the emotions and events associated with a story, play, or personal experience. In his tone poem Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Richard Strauss tries to depict

in music the events described in a novel of that title by the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900). The hero of Nietzsche’s story is the

ancient Persian prophet Zarathustra (Zoroaster), who foretells the coming of

a more advanced human, a Superman. (This strain in German Romantic philosophy was later perverted by Adolf Hitler into the cult of a “master race.”)

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Licensed to: iChapters User

Strauss’s tone poem begins at the moment at which

Zarathustra addresses the rising sun. The listener

may sense in the music the dawn of a new age, the

advent of an all-powerful superman, or simply the

rising of the sun (Fig. 1–6).

While the imposing title Thus Spoke Zarathustra may

seen foreign, and the mention of German philosophy intimidating, Strauss’s music is well known to

you. It gained fame in the late 1960s when used

as film music in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space

Odyssey. Since then it has sounded forth in countless

radio and TV commercials to convey a sense of high

drama. The music begins with a low rumble as if coming from the depths of the earth. From this darkness

emerges a ray of light as four trumpets play a rising

motive that Strauss called the “Nature Theme.” The

light suddenly falls dark and then rises again, ultimately to culminate in a stunning climax. How do

you describe a sunrise through music? Strauss tells

us. The music should ascend in pitch, get louder, grow

in warmth (more instruments), and reach an impressive climax. Simple as they may be, these are the technical means Strauss employs to convey musical meaning. Nowhere in the musical repertoire is there a more vivid depiction of the power of nature or the

potential of humankind.

Listening Guide

0:00

0:16

0:30

0:35

0:49

0:55

1:13

1:23

3

■

C H A P T E R

1

11

Cindy Davis

Listening to Music

F I G U R E 1–6

A fanciful depiction of the opening of Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra

with the rise of the all-powerful sun.

Richard Strauss

Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1896)

Intro

3

Rumbling of low string instruments, organ, and bass drum

Four trumpets ascend, moving bright to dark

(major to minor)

A drum (timpani) pounds forcefully

Four trumpets ascend again, moving dark to light

(minor to major)

A drum (timpani) pounds forcefully again

Four trumpets ascend third time

Full orchestra joins in to add substance to impressive succession of chords

Grand climax by full orchestra at high pitches

Use a downloadable, cross-platform animated Active Listening Guide, available

at www.thomsonedu.com/music/wright.

Listening Exercise 1

Intro

1–3

Musical Beginnings

This first Listening Exercise asks you to review three of the most famous “beginnings” in the entire repertoire of classical music. The following questions encourage

To take this Listening Exercise online and

receive feedback or email answers to your

instructor, go to ThomsonNOW for this chapter.

(continued)

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Licensed to: iChapters User

12

P A R T

I

■

The Elements of Music

you to listen actively, sometimes to just small details in the music. This first

exercise is designed to be user-friendly—the questions are not too difficult.

Beethoven, Symphony No. 5 (1808)—Opening

1. (0:00–0:05) Beethoven opens his Symphony No. 5

1

with the famous “short-short-short-long” motive and

then immediately repeats. Does the repetition present

the motive at a higher or at a lower level of pitch?

a. higher pitches

b. lower pitches

2. (0:22–0:44) In this passage, Beethoven constructs a

musical transition that moves us from the opening

motive to a more lyrical second theme. Which is true

about this transition?

a. The music seems to get slower and makes use of a

diminuendo.

b. The music seems to get faster and makes use of a

crescendo.

3. (0:38–0:44) How does Beethoven add intensity to the

conclusion of the transition?

a. A pounding drum (timpani) is added to the orchestra and then a French horn plays a solo.

b. A French horn plays a solo and then a pounding

drum (timpani) is added to the orchestra.

4. (0:42–0:44) Which combination of short (S) and long

(L) sounds accurately represents what the solo French

horn plays at the end of this transition?

a. SSSSL b. SSSSSL c. SSSLLL

5. (0:45–1:02) Now a more lyrical new theme enters

in the violins and is echoed by the winds. But has the

opening motive (SSSL) really disappeared?

a. Yes, it is no longer present.

b. No, it can be heard above the new melody.

c. No, it lurks below the new melody.

6. (1:13–1:21) Which is true about the end of this opening section?

a. Beethoven brings back the opening motive.

b. Beethoven brings back the material from the

transition.

c. Beethoven brings back the second, lyrical theme.

7. Student choice (no “correct” answer): How do you feel

about the end of the opening section, compared to

the beginning?

a. less anxious and more self-confident

b. less self-confident and even more anxious

Tchaikovsky, Piano Concerto No. 1 (1875)—Opening

8. (0:00–0:06) How many times does the French horn

play the descending motive?

a. once b. three times c. five times

9. (0:07–0:14) Which instrumental force plays the

chords first?

a. The orchestra plays them first (then the piano).

b. The piano plays them first (then the orchestra).

10. (0:15–0:43) As the violins play the melody, the piano

accompanies them with groups of three chords. What

is the position of the pitches of the three chords in

each group?

a. high, middle, low

b. middle, high, low

c. low, middle, high

2

11. (1:30–2:22) In the section of piano solo razzle-dazzle,

which sounds more prominently?

a. the four-note descending motive

b. the long, sweeping melody

12. (2:26–2:54) During this final statement of the melody, the piano is again playing chords as accompaniment. Now there are many more of them, but the

general direction of these chords is still what?

a. moving high to low b. moving low to high

13. (3:05–3:21) Tchaikovsky revisits which musical material to create this fade-out?

a. the four-note descending motive

b. the beginning of the sweeping melody

Strauss, Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1896)—Opening

14. (0:00–0:15) Which is true about the opening sounds?

3

a. The instruments are playing several different

sounds in succession.

b. The instruments are holding one and the same tone.

15. (0:16–0:20) When the trumpets enter and ascend,

does the low, rumbling sound disappear?

a. yes b. no

16. (0:16–0:22 and again at 0:35–0:43) When the trumpets

rise, how many notes (different pitches) do they play?

a. one b. two c. three

17. (0:30–0:35 and again at 0:49–0:54) When the timpani

enters, how many different pitches does it play?

a. one b. two c. three

18. (1:15–1:21) In this passage, the trombones enter and

play a loud counterpoint to the rising trumpets. In

which direction is the music of the trombone going?

a. up b. down

19. (1:27) At the very last chord, a new sound is added

for emphasis—to signal that this is indeed the last

chord of the climax. What is that sound?

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Rhythm

a. a crashing cymbal

b. a piano

c. an electric bass guitar

20. Student choice: You have now heard three very different

musical openings, by Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, and

orchestra (8)

symphony

orchestra (8)

motive (8)

crescendo (8)

diminuendo (8)

concerto (9)

C H A P T E R

2

13

Strauss. Which do you prefer? Which grabbed your

attention the most? Think about why.

a. Beethoven b. Tchaikovsky c. Strauss

Key Words

classical music (4)

popular music (4)

acoustic

instrument (4)

encore (6)

symphony (8)

movement (8)

■

chord (9)

melody (10)

pizzicato (10)

tone poem

(symphonic

poem) (10)

ThomsonNOW for Listening to Music, 5th Edition,

and Listening to Western Music will assist you in

understanding the content of this chapter with

lesson plans generated for your specific needs.

In addition, you may complete this chapter’s

Listening Exercise in ThomsonNOW’s interactive

environment, as well as download Active Listening Guides and other materials that will help you

succeed in this course.

Copyright 2008 Thomson Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.