The Rise and Possible Demise of Afrikaans as a Public

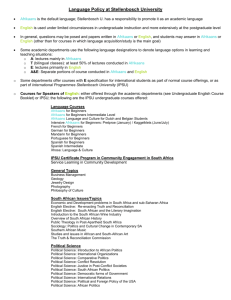

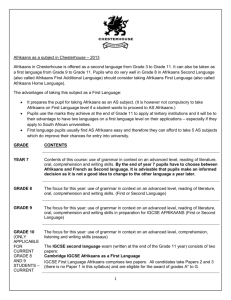

advertisement