Syllabus-Chazkel-Law-and-the-City-in-Lat-Am

advertisement

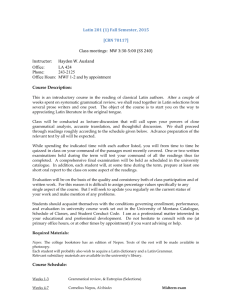

CUNY Graduate Center Spring 2016 LAW AND JUSTICE IN THE HISTORY OF THE CITY IN LATIN AMERICA History 77300 Syllabus (posted 1/22/16) class meets: classroom: instructor: instructor’s office: email: Tuesdays, 4:15 to 6:15 pm CUNY Graduate Center, Room TBA Amy Chazkel, Department of History Room 5405 (tel: 212-­‐817-­‐8463) amychazkel@gmail.com This doctoral-­‐level course examines the long history of cities in Latin America, from the early colonial era in the fifteenth century to the present day, with a particular focus on scholarship at the intersection of the study of the law and the humanities. We will consider topics that include, but are not limited to: the founding of cities as an expression of imperial power; gender and the question of private and public urban life; the centrality of urban slavery and freedpersons to the sociolegal history of Latin American cities; the long history of urban crime, justice, and policing; urban protest and social movements; architecture and power; and the history of struggles over control of urban space and time. A topic that we will treat in particular depth is the history of what has come to be called the “right to the city” as it developed out of centuries of struggles over urban resources throughout the region. In addition to our readings, students will work throughout the semester toward producing an in-­‐depth, publishable-­‐quality historiographic essay as a final project. The content of each student’s paper can be tailored to his or her own interests and disciplinary orientation. We will read, workshop, and learn from each other’s ongoing urban history research. This course is designed equally to explore the law and justice as crucial elements in the humanistic study of cities on the one hand, and, on the other, to familiarize students with a panorama of some of the most cutting-­‐edge new scholarship on Latin American history, from the colonial era to the present. Students in this course do not need to have any prior knowledge of Latin American history, and students from other disciplines are warmly welcomed. All required readings will be in English; reading knowledge or Spanish and/or Portuguese would expand the possibilities available for writing the final paper but is not a requirement. Course learning goals: *To gain in-­‐depth historiographic knowledge of trends in the study of the sociolegal dimension of Latin American urban history, both in our contemporary era and over the last century, in the context of the broader historiography of both Latin American history and comparative urban history; 1 *To become familiar with the historical trajectory of the rise of cities in Latin America, from the fifteenth century to the contemporary era, and to have a deep understanding of both the similarities across different cities in the region and a critical perspective of the very concept of “Latin America” by way of the great diversity of urban histories in the region and the cities’ connections to other parts of the world; *To consider deeply and become conversant in the theoretical and methodological questions that the use of judicial and legal records as historical sources raise; *To understand and know how to apply some of the key analytical tools in urban history, many of which are of inter-­‐ and transdisciplinary provenance, such as the study of space and place, scale, urban temporality, social mobility, the regulation of daily life, and the formation of urban networks; *To gain experience in reviewing scholarly books, both in writing an in group discussions, and also in respectful yet trenchant critique of peers’ work and ideas; and *To gain experience in producing a masterful piece of critical historiographic writing. I will hold office hours from 2:30 to 4:00 pm on Tuesdays (office location: room 5405). In addition, I am available to meet with students by appointment; please contact me to set up a mutually convenient time. Please note that the quickest and most effective way to contact me is by email. I can also be reached by phone at either (212) 817-­‐8463 or (718) 997-­‐5371; please note that if you wish to leave a message, email is much more reliable and effective than leaving a voicemail message on either one of those numbers. Texts for this class will be available for purchase on Amazon or any major bookseller. You will also find all of these texts on reserve at the library. 1. Brodwyn Fischer and Bryan McCann, eds., Cities from Scratch: Poverty and Informality in Urban Latin America (Duke University Press, 2014) 2. Ernesto Capello, The City at the Center of the World: Space, History, and Modernity in Quito (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011) 3. Guadelupe García, Beyond the Walled City: Colonial Exclusion in Havana (University of California Press, 2015) 4. Bianca Premo, Children of the Father King: Youth, Authority, and Legal Minority in Colonial Lime (UNC Press, 2005) 2 5. John Collins, Revolt of the Saints: Memory and Redemption in the Twilight of Brazilian Racial Democracy (Duke University Press, 2014). 6. Pablo Piccato, City of Suspects: Crime in Mexico City, 1900-­‐1931 (Duke University Press, 2001) There are required readings (journal articles and book chapters) other than the published books listed above; I will send these to you electronically if they are not available in the library e-­‐journals or online for free. Optional survey texts: Students who do not have a general knowledge of the sweep of Latin American history may wish to obtain one or more of the following books, and read or refer to them as needed. The following list, which is selective rather than comprehensive, includes some of the most frequently assigned Latin American history survey texts: 1. Burkholder and Johnson, Colonial Latin America 8th ed. (2012) 2. Schwartz and Lockhart, Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil 3. John Charles Chasteen, Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America 3nd ed. (2011) 4. Leslie Bethell, see his numerous titles on Cuba, Brazil, Chile, and Latin America 5. Thomas Skidmore, Peter Smith, and James Green, Modern Latin America, 7th ed. (2009) 6. Teresa Meade, A Brief History of Brazil 2nd ed. (2009) 7. George Reid Andrews, Afro-­‐Latin America, 1500-­‐2000 (2004) This is a reading-­‐intensive course that is designed to get you up to speed on a sprawling, interdisciplinary field of study. Our day-­‐to-­‐day work together will consist of our working through, synthesizing, and mastering this material; along the way, each of you will both forge links to your already-­‐existing academic (and/or political) interests and develop your own “turf” in the form of a historiographic research project, due just after the end of the term. To fulfill those goals, it is truly imperative that you come to class having completed all of the readings and, ideally, with the readings themselves in hand so that we can refer to and discuss particular passages of the text when appropriate. You should also focus your energies and attention, especially at the beginning of the semester, on making sure that you have a method for noting and storing information about important insights that come to you as your read, bibliographic suggestions for your own work, and other types of information. Developing effective information-­‐management and study techniques is a trial-­‐ and-­‐error process that can be frustrating at times but, once developed, will provide you with lifelong tools for organizing and storing the increasing body of material that you are now in the process of accumulating. In each class, we will devote some time to discussing the mechanics of scholarship as well as the content of our readings. Please come to class 3 prepared to discuss which citations in the readings caught your eye, what ideas gave you food for thought, and how you plan to store and to follow up on these bibliographic references and insights in the future. In addition to completing the readings assigned for each week, the work required for this class includes the following: 1. Review essay. Each student will be assigned to one week out of the semester in which (s)he must to submit a concise analytical essay that responds to and reflects on the readings for that week. The format for this assignment should be loosely modeled after the scholarly review essay; for examples of what this genre of scholarly writing looks like, please refer to such journals as the Latin American Research Review and the American Historical Review, which regularly feature review essays. You are strongly encouraged to do additional reading beyond the texts assigned for your week. I have listed some suggested readings for each week for this purpose and would be happy to provide additional guidance in that regard. During our first class meeting, I will circulate a sign-­‐up sheet on which each student will commit to one week’s group of readings. On the Friday prior to our Tuesday afternoon class meeting, the student(s) assigned to write the review essay for that week must submit the essay electronically to the entire class using our email list. Please be sure to send your essay promptly by 8:00 pm. Please take this deadline seriously, out of respect for your classmates and the need for them to have time to give the review essay of the week their attention before our class meeting. Prior to our class meeting, students are required to read their peer’s essay for that week and to come to class prepared to discuss it along with the other readings. 2. Commentary. In addition to signing up to write a review essay, each student will sign up to be the commentator on a given week (necessarily a different week from the one during which (s)he is signed up to submit the written review essay). The Commentary will take place at the beginning of our class meeting and will consist of a brief oral discussion of both the readings for that week and his/her peer’s written Review Essay submitted on the readings. Ideally, commentary should critically engage the assigned readings as well as the Review Essay, using these readings as a point of departure to start our class session with an analytical discussion of the topic scheduled on the syllabus. The person preparing the commentary for the week is encouraged (but not required) to bring in outside readings, ideas from your other courses or your own research, images, artifacts, and so on. You are also strongly encouraged to bring our discussions and texts from prior classes into your Commentary. This need not be lengthy or formal—10 minutes is sufficient—but should be a serious, carefully and thoughtfully prepared presentation. (In other words, please do not simply speak off the cuff; make sure to think in advance about and plan your comments.) No written work needs to be submitted whatsoever for this assignment, it is an oral presentation. 3. Final paper, “Problems in the Study of the Law and the City in Latin America.” You will have one major writing assignment to complete outside of class. 4 You must write a historiographic essay of approximately 15-­‐20 pages on any theme related to the subject matter of this course that has presented a particular problem to historians or other scholars. Since this is a history class with a distinctively interdisciplinary orientation, you are very welcome also to draw on works from disciplines other than history. Your final paper, however, must prominently feature a strong consciousness about historical analysis and a critical approach to the study of processes of change. I am happy to work closely with students from disciplines other than history to help them think through how historical thinking can help advance their own scholarship through designing a paper topic suited to their own broad interests and concerns. This essay is designed to encourage you to delve deeply into the secondary literature, and your main sources are expected to be the works of historians and other scholars. However, please note that any students who already have gathered archival data or who wish to break ground on a research project may certainly bring primary sources into this paper. If you are interested in writing such a paper, you are encouraged to meet with me for some suggestions about how to integrate primary-­‐source material into your historiographic essay, or how to use this assignment as a way in to an incipient dissertation or other research project. This essay will be due on the Wednesday following our final class meeting. As the deadline draws nearer, I will distribute handouts that will help you with this essay and will provide complete instructions and guidelines for its submission. We will devote some time in the last two class sessions for each student to present his or her paper project to the class. Please note that this term paper assignment has two parts. In class on April 5th, you should submit to me a paper prospectus: a short essay (one to two pages in length, double-­‐spaced with 12-­‐point font) describing the expected topic of your paper, making at least a preliminary argument about the scholarly importance of your chosen topic, and citing at least three scholarly works of history that you intend to use as sources; in addition to these three works, I strongly encourage you to submit a longer bibliography so that I can give you the best possible feedback and suggestions about where your paper is headed. *** The following is a day-­‐by-­‐day schedule of topics we will cover in class and the corresponding readings assigned for each day. Each reading below with an asterisk (*) is either an article or book excerpt and is either freely available online (in the library’s e-­‐journals, for example) or will be distributed electronically to the class at least a week prior to the class on which we will discuss it. 5 I. Introduction to the Sociolegal History of Cities: Laying out the Terms of the Discussion Tuesday, February 2 Class 1: introduction: terms, problems, and disciplinary approaches regulating public life/ the question of scale Please complete the following readings prior to our first class meeting; the required readings are in published scholarly journals available from the library website or available for free online: *Hendrick Hartog, “Pigs and Positivism,” Wisconsin Law Review (1985), 899-­‐ 935. *Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, chapters 7 and 8. It would be helpful at least to glance at the prologue and introduction. Book is available for free online: http://sduk.us/afterwork/arendt_the_human_condition.pdf *Mariana Valverde, "Seeing like a city: the dialectic of modern and premodern knowledges in urban governance", Law and Society Review 45 no. 2 (June 2011), 277-­‐313. *OPTIONAL/ SUGGESTED: Neil Smith and Setha Low, “Introduction: The Imperative of Public Space,” in Smith and Low, eds., The Politics of Public Space (Routledge, 2005). (Tuesday, February 9, classes follow a Friday schedule, this class does not meet) Tuesday, February 16 Class 2: the law and the city in the colonial and postcolonial world SPECIAL EVENT: Professor John Collins (Queens College and the Graduate Center, Anthropology) will lead the class today. John Collins, Revolt of the Saints: Memory and Redemption in the Twilight of Brazilian Racial Democracy (Duke University Press, 2014). *Kathryn Burns, “Notaries, Truth, and Consequences,” American Historical Review 110:2 (April 2005), 350–379. *OPTIONAL/ SUGGESTED: Webb Keane, “Signs are not the Garb of Meaning: On the Social Analaysis of Material Things,” in D. Miller, ed., Materiality (Duke Univeristy Press, 2006), 182-­‐205. Available online at: 6 http://is.muni.cz/el/1423/podzim2015/SOC571/um/59556777/Keane_Soc ial_Analysis_of_Material_Things.pdf Tuesday, February 23 Class 3: approaches to the legal histories of cities as colonial places: the long history of comparative urban history, and the problems of sovereignty and scale *Sérgio Buarque de Holanda, “Sowers and Builders,” (in the original: “O semeador e a ladrilhador”) in Roots of Brazil, trans. G. Harvey Summ (University of Notre Dame Press, 2013). Optional/ recommended, in same volume: Pedro Meira Monteiro, “Why Read Roots of Brazil Today?,” ix-­‐xx. *Richard Ross and Philip Stern, “Reconstructing Early Modern Notions of Legal Pluralism,” in Benton, ed., Legal Pluralism and Empires, 109-­‐141. *Burbank and Cooper, “Rules of Law, Politics of Empire,” in Benton, ed., Legal Pluralism and Empires, Chapter 11 *Antonio Hespanha, “Early Modern Law and the Anthropological Imagination of Old European Culture,” in John A. Marino, eds., Early Modern History and the Social Sciences: Testing the Limits of Braudel’s Mediterranean (Truman State University Press, 2002), 191-­‐204. OPTIONAL/ SUGGESTED: Armus, Diego, and John Lear. “The Trajectory of Latin American Urban History.” Journal of Urban History 24.3 (1998): 291– 301. II. COLONIALISM AND IMPERIAL LAW IN LATIN AMERICAN CITIES, C. 1500-­‐ 1820 Tuesday, March 1 Class 4: ordinances and placing cities on the map: Spanish America Guadelupe García, Beyond the Walled City: Colonial Exclusion in Havana (University of California Press, 2015) *The Laws of the Indies: Ordinances for the Discovery, the Population, and the Pacification of the Indies (excerpts), 1573 * Angel Rama, The Lettered City (trans. Chasteen, Duke UP, 1996), excerpts (translator’s introduction and Chapters One, “The Ordered City,” and Three, “City of Protocols” 7 OPTIONAL/ RECOMMENDED: * Mark A. Burkholder, “Bureaucrats” (chapter 4), in Louisa Schell Hoberman and Susan Migden Socolow, eds., Cities and Society in Colonial Latin America. Pp. 77-­‐103. OPTIONAL/ RECOMMENDED * Jay Kinsbruner, The Colonial Spanish-­‐ American City: Urban Life in the Age of Atlantic Capitalism. University of Texas Press, 2005, chapters 1 and 2. OPTIONAL/ RECOMMENDED : * Morse, Richard. “The Urban Development of Colonial Spanish America.” In The Cambridge History of Latin America. Vol. 2, Colonial Latin America. Edited by Leslie Bethell, 67–104. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1984. Tuesday, March 8 Class 5: colonial law and regulation in the 18th century city Bianca Premo, Children of the Father King III. INDEPENDENCE AND POST-­‐COLONIAL CITIES IN LATIN AMERICA Tuesday, March 15 Class 6: national culture, urban culture, and the law in the century of postcolonial nation-­‐building Ernesto Capello, The City at the Center of the World *Mariana Valverde, Cronotopes of Law: Jurisdiction, Scale and Governance (Routledge, 2015), excerpts Tuesday, March 22 Class 7: Urban life, race/ethnicity, “public rights” and the problem of legal equality in the shadow of slavery *excerpt from James E. Sanders, Vanguard of the Atlantic World: Creating Modernity, Nation, and Democracy in Nineteenth-­‐Century Latin America (Duke University Press, 2014), Chapter 3. *Rebecca Scott, "Public Rights and Private Commerce: A Nineteenth-­‐Century Atlantic Creole Itinerary," Current Anthropology (April 2007): 237-­‐256. *Sidney Chalhoub, “The Precariousness of Freedom in Slave Society,” International Review of Social History 56:3 (2011), 405-­‐439. 8 OPTIONAL/ SUGGESTED: *Sandra Lauderdale Graham, “Writing from the Margins: Brazilian Slaves and Written Culture,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 49:3 (2007), 611 Tuesday, March 29 Class 8: the disciplinary state and municipal power Please note that this will be an independent study day and our class will not meet. The readings for this week are still required and will be discussed in our following class on April 5, along with the other readings listed below under that date. I suggest that you use this extra time to make substantial progress on your final papers; your paper prospectus is due in class next week! Pablo Piccato, City of Suspects: Crime in Mexico City, 1900-­‐1931 (Duke University Press, 2001) * Centeno, “The disciplinary society in Latin America,” in Centeno and López-­‐ Alvez, eds., The Other Mirror: Grand Theory through the Lens of Latin America (Princeton University Press, 2001) *Steven Palmer, “Confinement, Policing, and the Emergence of Social Policy in Costa Rica, 1880-­‐1935,” in Salvatore and Aguirre, The Birth of the Penitentiary in Latin America: Essays in Criminology, Prison Reform, and Social Control, 1830-­‐1940 (UT Press, 1996). * OPTIONAL/ SUGGESTED: excerpt from Alan Hunt, Governance of the Consuming Passions, Chapter 2 Tuesday, April 5 Class 9: the disciplinary state and municipal power, part 2: drugs, and the transnational legal histories of cities *selections from Radical History Review dossier on police museums in Latin America, issue 113, (2012) * Elaine Carey, article on Mexican nacrotraffic, tba *Isaac Campos, “Degeneration and the Origins of Mexico’s War on Drugs” Mexican Studies 2010. *Alma Guillermprieto, “Medellín,” in The Heart that Bleeds, Latin America Now (Vintage, 1995). This can also be accessed in the New Yorker archive (“Letter from Medellín,” New Yorker, April 22, 1991): http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1991/04/22/letter-­‐from-­‐medellin 9 * OPTIONAL/ SUGGESTED: Kate Swanson “Zero Tolerance in Latin America: Punitive Paradox in Urban Policy Mobilities,” Urban Geography 34:7 (2013), 972-­‐988. OPTIONAL/ SUGGESTED: Froylán Enciso, “When Drugs were Legal in Mexico,” counterarchives.org, http://counterarchives.org/2015/05/31/when-­‐drugs-­‐were-­‐legal-­‐in-­‐mexico-­‐ by-­‐froylan-­‐enciso/ Please note: Prospectus due in class. Tuesday, April 12 Class 10: urban protest and the place of the law *Anton Rosenthal. “Spectacle, Fear, and Protest: A Guide to the History of Urban Public Space in Latin America.” Social Science History 24.1 (Spring 2000): 33–73. *Alejandro Velasco, “‘A Weapon as Powerful as the Vote’: Urban Protest and Electoral Politics in Venezuela, 1978-­‐1983,” Hispanic American Historical Review 90:4 (2010): 661-­‐695. *E. P. Thompson, “Moral Economy of the English Crowd.” * Adrian Randall and Andrew Charlesworth, “The Moral Economy: Riot, Markets, and Social Conflict,” in Randall and Charlesworth, eds., Moral Economy and Popular Protest, Chapter 1. III. CONTEMPORARY CITIES Tuesday, April 19 Class 11: planned cities, modernism *Barry Bergdoll, “Learning from Latin America: Public Space, Housing, and Landscape,” in Bergdoll et als, Latin American in Construction: Architecture 1955-­‐1980 (NY: Museum of Modern Art, 2015), 16-­‐39. *James Holston, “The Spirit of Brasília: Modernity as Experiment and Risk”, in Rebecca Birón, City/ Art: The Urban Scene in Latin America (Duke University Press, 2009), 85-­‐114. *excerpts from James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (Yale University Press, 1999), 10 Chapters 3 and 4. (If you have access to the whole book, please skim chapters 1 and 2 to help you understand Scott’s argument.) (April 22-­‐30, Spring Break) Tuesday, May 3 Class 12: urban informality Brodwyn Fischer and Bryan McCann, eds., Cities from Scratch: Poverty and Informality in Urban Latin America (Duke University Press, 2014) Tuesday, May 10 Class 13: the right to the city: its long history SPECIAL EVENT: Professor Hendrik Hartog (Class of 1921 Bicentennial Professor in the History of American Law and Liberty, Department of History and Program in American Studies, Princeton University) will join the class today as guest discussant. *Hendrik Hartog, “Pigs and Positivism” (Please revisit this article, which we first saw on the first day of the semester.) *David Harvey, “The Right to the City,” New Left Review 53 (September-­‐ October 2008) *David Harvey, preface to Rebel Cities, “Henri Lefebvre’s Vision” *Excerpt from Henri Lefebvre, Writings on Cities. *City Statute of Brazil (Federal Law 10257, 2001) Please also see this useful commentary on the statute: http://www.citiesalliance.org/node/1947 *Don Mitchell, excerpts from The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space (The Guilford Press, 2003), “Conclusion: The Illusion and Necessity of Order” Tuesday, May 17 Class 14: is there something called an “Urban Global South”?: the law and the city in the postcolonial world *Orlando Patterson, “Freedom, Slavery, and the Modern Construction of Rights” in Owlen Hufton, ed., Historical Change and Human Rights (New York: Basic Books, 1995). 11 *Mike Davis, “Planet of Slums,” New Left Review 26 (March-­‐April 2004), 5-­‐34. *Ananya Roy, “Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35:2 (March 2011), 223-­‐238. * Nelson Brissac Peixoto, “Latin American Megacities: The New Urban Formlessess,” in Rebecca Biron, ed., City/Art: The Urban Scene in Latin America (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009), pp. 233-­‐250 Final papers due May 20th in my box in the Graduate Center History office. Please make sure you have submitted the paper by 4pm at the latest. 12