Guide to Off-form Concrete Finishes

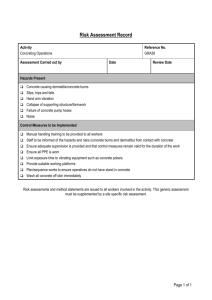

advertisement