The Capital Cost Allowance System

advertisement

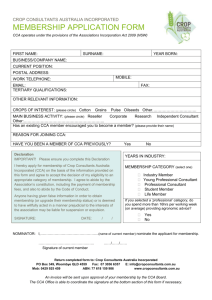

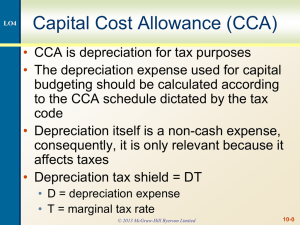

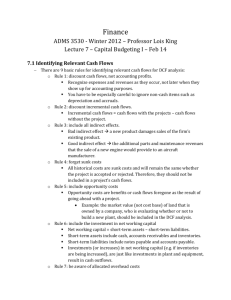

The Capital Cost Allowance System Israel Mida and Kathleen Stewart* P RÉCIS Cet article comporte un historique et une analyse du régime canadien de déduction pour amortissement, qui sert de base pour l’établissement de l’amortissement d’immobilisations à l’égard de l’impôt. Les auteurs résument les éléments clés du régime actuel, y compris les genres de biens admissibles à la déduction pour amortissement, la méthode de calcul des demandes de déduction pour amortissement et les principales dispositions qui ont été adoptées au fil des ans afin de restreindre les demandes de déduction pour amortissement. Les auteurs évalue ensuite l’équité, la simplicité, l’à-propos et la compétitivité du régime, et ils examinent les facteurs qui influenceront les modifications qui y seront apportées. ABSTRACT This article presents a review and analysis of the Canadian capital cost allowance system, which establishes the basis for the depreciation of capital property for tax purposes. The authors summarize the key elements of the current system, including the types of property that are eligible for capital cost allowance, the method of calculating capital cost allowance claims, and the major provisions that have been introduced over the years to restrict capital cost allowance claims. The authors then assess the fairness, simplicity, adequacy, and competitiveness of the system and consider the factors that will influence future changes to it. INTRODUCTION This article presents a review and analysis of the Canadian capital cost allowance ( CCA) system. For many taxpayers, capital expenditures represent the most significant cost of doing business. Paragraph 18(1)(b) of the Income Tax Act 1 prohibits the deduction of capital expenditures; however, paragraph 20(1)(a) allows a taxpayer to deduct an amount with respect to the capital cost of property to the extent allowed by the Income Tax Regulations. The regulations contain a multitude of detailed rules that make up the CCA system. * Of Coopers & Lybrand, Toronto. 1 RSC 1985, c. 1 (5th Supp.), as amended (herein referred to as “the Act”). Unless otherwise stated, statutory references in this article are to the Act. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1245 1246 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE The first section of the article summarizes the depreciation system under the Income War Tax Act of 1917 (IWTA) and then the basic CCA system. As the current CCA system has evolved over a period of nearly 50 years, the article deals with only the highlights of the amendments made during that time. Table 1 provides a chronological summary of the key amendments, excluding rate changes. The second section of this article provides an assessment of the CCA system. The final section considers the future of the system. BACKGROUND: THE SYSTEM BEFORE 19492 The CCA system was designed, in large part, to address the many concerns that taxpayers had with its predecessor, the depreciation system introduced as part of the IWTA. The IWTA gave the minister of national revenue absolute discretion in determining how much depreciation, if any, would be allowed to a particular taxpayer for tax purposes.3 Over time, an informal set of rules developed as the maximum rates that were generally allowed by the minister for various types of assets became known within the business community. However, since rates for particular taxpayers could still be negotiated, there was no assurance that the minister would always be consistent and treat taxpayers equally. Once depreciation rates were set for a taxpayer, they had to be strictly adhered to unless otherwise allowed by the minister. Even in a loss year, the minister required that a taxpayer claim a minimum of 50 percent of its usual tax depreciation allowance. If a taxpayer claimed a low rate of depreciation in a given year owing to poor profitability, there was no opportunity to amend the claim subsequently if profitability was higher in a later year. The system was designed to recognize the wear and tear of property used to earn income. Depreciation was generally calculated on a straightline basis over what the minister estimated to be the useful life of the property. The effect of obsolescence on the loss in value of the property was not recognized in the setting of the rates. If property was sold or scrapped before it was fully depreciated, no further depreciation was allowed, and any resulting loss was considered capital in nature and thus not recognized for tax purposes. (Capital gains and losses were “nothings” until 1972.) In 1940, the legislation was amended to provide that tax depreciation could not be claimed in excess of the depreciation that was booked for accounting purposes. The result was that taxpayers established accounting policies for depreciation that would allow for the maximum tax 2 For further discussion of the predecessor system, see Canada, Department of Finance, 1976 Budget, Budget Paper C, “Capital Cost Allowances,” May 25, 1976; Robert W. Davis, Capital Cost Allowance, Studies of the Royal Commission on Taxation no. 21 (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1966); and Lancelot J. Smith, “Twelve Years of Capital Cost Allowances,” in Corporate Management Conference 1961, Canadian Tax Paper no. 24 (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1961), 15-32. 3 The Income War Tax Act, RSC 1927, c. 97, section 5(a). (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 THE CAPITAL COST ALLOWANCE SYSTEM Table 1 1247 Canadian Tax Depreciation Systems: Summary of Milestones Year Milestone 1917 . . . . . . 1940 . . . . . . Introduction of depreciation system in Income War Tax Act Introduction of requirement that tax depreciation not exceed accounting depreciation Introduction of accelerated depreciation and a limited form of recapture of accelerated depreciation Introduction of capital cost allowance system Repeal of requirement that tax depreciation not exceed accounting depreciation Restrictions on CCA claims for rental properties Restrictions on CCA claims for leasing properties Introduction of half-year rule Available-for-use rules Restrictions of CCA for passenger vehicles Specified leasing property rules Revision of rules governing non-arm’s-length transfers of assets 1949 1954 1972 1976 1981 1987 ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 1989 . . . . . . 1995 . . . . . . writeoff, whether or not the method was appropriate for accounting purposes. When the government abandoned this limitation in 1954, a number of taxpayers restated their accounting depreciation for financial statement purposes for prior years.4 Beginning in 1940, accelerated depreciation was permitted in order to encourage the expansion of wartime production facilities. A limited form of recapture also was introduced in that year. In 1944, a further legislative amendment provided for double depreciation on up to 80 percent of the cost of new investment. This change was designed to facilitate the transition to peace and to stimulate the economy. These measures appear to be the first attempts by the federal government to use depreciation as a fiscal tool. Although the system from 1917 to 1948 permitted an allowance that closely approximated that provided by business in financial statements, concerns of business about the proper exercise of ministerial discretion and the lack of recognition of obsolescence made changes necessary.5 These concerns ultimately led to the introduction of the CCA system. CAPITAL COST ALLOWANCE SYSTEM Overview The CCA system became effective January 1, 1949. It was designed to be simpler and more equitable than its predecessor. Although many modifications have been made over the years, the basic structure of the original CCA system remains intact today. The system gives taxpayers the statutory right to make a discretionary claim in respect of an eligible capital acquisition equal to any amount up to the maximum allowed under the 4 Davis, 5 Ibid., supra footnote 2, at 61. at 1. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1248 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE regulations. CCA is generally calculated on a declining balance basis at the prescribed rate on the undepreciated capital cost (UCC) of depreciable property grouped in prescribed classes. The myriad of factors to be considered in determining a CCA claim are discussed below under three major headings: 1) eligibility for inclusion in CCA classes, 2) calculation of CCA, and 3) restrictions on CCA claims. Eligibility for Inclusion in CCA Classes As noted above, the CCA system applies to capital expenditures. Jurisprudence has established a number of criteria that may be considered in determining whether an expenditure is capital in nature. For example, capital expenditures generally produce an enduring benefit, while expenditures of a current nature produce an immediate benefit but have little or no long-term effect.6 Property must be included in the regulations in order to be eligible for CCA. 7 The regulations apply to tangible depreciable assets such as buildings, equipment, and furniture and fixtures, and to intangibles such as patents, franchises, and leasehold improvements.8 No depreciation is allowed for land.9 Goodwill and other intangibles are entitled to a tax writeoff as eligible capital expenditures.10 This tax writeoff is not discussed here but has been covered thoroughly elsewhere. 11 Regulation 1102 specifically excludes from the CCA classes certain property including the cost of property that is deductible in computing income, inventory, property that was not acquired for the purpose of gaining or producing income, property acquired that qualifies for a deduction under section 37 of the Act, land, and property owned by a non-resident person that is situated outside Canada. In addition, class 8 provides a number of other exclusions.12 6 British Insulated and Helsby Cables v. Atherton, [1926] AC 205 (HL). Other criteria that may be considered in determining whether an expenditure is of a current or capital nature are summarized in Interpretation Bulletin IT-128R, “Capital Cost Allowance— Depreciable Property,” May 21, 1985. 7 Paragraph 20(1)(a). 8 Assets included in CCA classes are summarized in regulation schedules II to VI. 9 Regulation 1102(2). 10 Defined in subsection 14(5). 11 See, for example, Ronald W. Larter, “Capital Cost Allowance and Eligible Capital Property: Tax Reform Implications,” in Report of Proceedings of the Fortieth Tax Conference, 1988 Conference Report (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1989), 27:1-27; and Joseph A. Stainsby, “Recent Developments in Capital Cost Allowance and Eligible Capital Expenditures,” in Current Developments in Measuring Business Income for Tax Purposes, 1981 Corporate Management Tax Conference (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1982), 167-207. 12 Regulation schedule II, class 8. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 THE CAPITAL COST ALLOWANCE SYSTEM 1249 Ownership An asset can generally be included in a CCA class only when the taxpayer has acquired a capital property or a leasehold interest in capital property for the purpose of gaining or producing income.13 The taxpayer will generally be considered to have acquired a depreciable property at the earlier of the day on which the taxpayer obtains title to it and the date on which the taxpayer has all the incidents of title, such as possession, use, and risk. A number of court cases have considered the issue of ownership, particularly in the context of lease arrangements.14 Available-for-Use Rules The timing of the inclusion of an asset in the UCC of a class is also affected by the “available-for-use rules,” which were introduced as part of the 1987 tax reform. These rules, contained in subsections 13(26) to (32), prevent the taxpayer from claiming CCA until the time the property is “available for use.” The time at which property is available for use is defined in subsection 13(27) for property other than buildings and in subsection 13(28) for buildings. Each of these provisions includes a two-year rolling start rule, providing that property that has not otherwise become available for use is deemed to be available for use in the second taxation year following the year in which the cost was incurred by the taxpayer. The application of the available-for-use rules may be limited in the third and subsequent years of a long-term project if the taxpayer elects under subsection 13(29) to use the “long-term project rule.” The taxpayer may make the election in the first taxation year that begins more than 357 days after the end of the taxation year in which the taxpayer first incurred expenditures in respect of the project. When this election is made, only expenditures in excess of certain threshold amounts in the third and subsequent years will be subject to the available-for-use rules.15 Calculation of CCA For purposes of calculating CCA, assets are grouped in prescribed classes. CCA is generally calculated by applying the prescribed CCA rate to the UCC of each class at the end of a taxation year. 16 Table 2 lists the classes 13 See the definitions of “depreciable property” and “undepreciated capital cost” in subsection 13(21). 14 See, for example, MNR v. Wardean Drilling Ltd., 69 DTC 5194 (Ex. Ct.); and The Queen v. Henuset Bros. Ltd. [No. 1], 77 DTC 5169 (FCTD). Additional cases are summarized in Thomas S. Gillespie, “Lease Financing,” in Income Tax and Goods and Services Tax Considerations in Corporate Financing, 1992 Corporate Management Tax Conference (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1993), 7:1-43. 15 An example of the long-term project rule is provided in the technical notes to Bill C-18: Canada, Department of Finance, Explanatory Notes to Legislation Relating to Income Tax (Ottawa: the department, May 1991), 186-89. For further discussion of the available-for-use rules, see Bruce R. Sinclair, “Depreciable Property: A Review of Recent Legislative Developments,” in Report of Proceedings of the Forty-Third Tax Conference, 1991 Conference Report (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1992), 26:1-20. 16 Regulation 1100(1)(a). (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1250 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE Table 2 Canadian CCA Rates as of 1995 Asset category Class for tax purposes Building . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Manufacturing machinery and equipment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Passenger vehicles . . . . . . . . . . . . . Automobiles and trucks . . . . . . . . . R & D assets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Furniture and fixtures . . . . . . . . . . . Computer hardware . . . . . . . . . . . . Computer software . . . . . . . . . . . . . Leasehold improvements . . . . . . . . Patents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 43 10.l 10 na 8 10 10 12 13 14 44 Method and rate applied 4% DB 30% DB 30% DB 30% DB 100%a 20% DB 30% DB 30% DB 100% SL over longer of 5 years and lease term plus first renewal term SL over life 25% DB DB: declining balance SL: straightline a 100% deductible in the year incurred pursuant to paragraph 37(1)(b). and the current prescribed rates that apply to the most common depreciable property.17 Although CCA is calculated on a declining balance basis for most classes, the straightline method is prescribed for some classes.18 As noted above, CCA is a discretionary deduction, and the taxpayer may claim any amount up to the maximum prescribed by the regulations. Importantly, Revenue Canada does permit the revision of previous CCA claims in some circumstances.19 UCC, on which the CCA for a particular class is calculated at any time, is determined in accordance with a formula set out in subsection 13(21) of the Act. The issues relevant to the calculation of UCC are discussed below under the following headings: • additions to UCC, • deductions from UCC, • adjustments to capital cost, 17 Schedules II to VI contain detailed lists of the asset classifications and the applicable rates. 18 For example, regulation 1100(1)(c) provides that class 14 assets (licences or franchises) are calculated on a straightline basis over the life of the asset. A straightline formula is provided in schedule III of the regulations for class 13 assets (leasehold improvements). 19 Revisions to claims in taxable years are generally permitted only where the revisions cause no change to assessed tax for taxable years unless the period for filing a notice of objection has not expired. Revisions to claims in non-taxable years are generally permitted provided that there is no change to the tax payable for the year or any other year filed. Revenue Canada’s policy is summarized in Information Circular 84-1, “Revision of Capital Cost Allowance Claims and Other Permissive Deductions,” July 9, 1984. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 THE CAPITAL COST ALLOWANCE SYSTEM 1251 • recapture, • terminal losses, and • separate classes. Additions to UCC The following amounts must be added to UCC: • The capital cost to the taxpayer of depreciable property of a class acquired by the taxpayer. Capital cost of a property is generally the purchase price plus any other related costs that must be incurred in order to make the asset operational (for example, installation and delivery charges).20 There are a number of provisions that may affect the amount included in respect of the capital cost of a property. These are discussed below under the heading “Adjustments to Capital Cost.” • All amounts included in income as recapture of CCA claimed in a previous taxation year. The recapture provisions are discussed below. • Repayments of assistance, inducements, or reimbursements received in respect of depreciable property of the class occurring after the disposition of the asset. Deductions from UCC The calculation of UCC includes the following deductions: • Total depreciation previously allowed to the taxpayer for property of the class. Total depreciation is defined to be all CCA claimed plus any terminal losses previously allowed under subsection 20(16).21 Terminal losses are discussed in detail below. • The lesser of proceeds of disposition and the original capital cost of the disposed of property. The terms “disposition of property” and “proceeds of disposition” are defined in subsection 13(21). A disposition of property includes any transaction or event that entitles a taxpayer to proceeds of disposition of property. Proceeds of disposition include the sale price of property that has been sold, compensation for property unlawfully taken, and compensation for property damaged or destroyed. • Investment tax credits claimed after the related property is sold. • Certain assistance received in respect of a property subsequent to the disposition of that property. Adjustments to Capital Cost The Act provides for the following adjustments to the capital cost otherwise included in a UCC pool of property: 20 The term “capital cost” is not defined in the Act. Revenue Canada has summarized its definition in paragraph 8 of Interpretation Bulletin IT-285R2, “Capital Cost Allowance—General Comments,” March 31, 1994. 21 Subsection 13(21). (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1252 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE • Where a property has been acquired pursuant to a section 85 election, the capital cost of the property will be the “elected amount.”22 • Where a depreciable property has been acquired from a non-arm’slength party, subsection 85(5.1) applies to override subsection 85(1) if the transferor has an inherent terminal loss with respect to the property. It deems the capital cost of the property to the transferee to be the lesser of the transferor’s cost and the UCC attributed to the particular property. Subsection 85(5.1) is to be repealed with effect after April 26, 1995 as a result of the introduction of proposed subsection 13(21.2),23 which limits the capital cost to the transferee to the FMV of the asset. Proposed subsection 13(21.2) is discussed further below under the heading “Terminal Losses.” • Where a property has been acquired from a non-arm’s-length transferee, paragraph 13(7)(e) may apply to reduce its capital cost where the transferor has recognized a capital gain on the disposition. • Where a taxpayer has acquired anything from a person with whom the taxpayer was not dealing at arm’s length for an amount in excess of FMV, the taxpayer is deemed by paragraph 69(1)(a) to have acquired it at FMV. • Where an amount has been paid in respect of the acquisition of property or services, section 68 permits the minister to reallocate the proceeds between the various assets or services if some or all of the values specified are considered unreasonable.24 • Immediately before an acquisition of control, a taxpayer may elect to have a deemed disposition and reacquisition of each capital property at an amount between the adjusted cost base and the FMV of the property. 25 For purposes of calculating CCA, the capital cost of the reacquired property is deemed by paragraph 13(7)(f ) to equal the original capital cost plus three-quarters of the realized gain. • Where government assistance (such as a grant, subsidy, or forgivable loan) or an investment tax credit has been received in respect of the 22 There are a number of provisions that apply to limit the “elected amount.” Paragraph 85(1)(e) provides that the elected amount cannot be less than the least of the UCC of the class, the cost to the taxpayer of the property, and the fair market value (FMV) of the property. Paragraph 85(1)(b) deems the elected amount to equal the FMV of non-share consideration where the agreed amount is less than the FMV of non-share consideration. Paragraph 85(1)(c) restricts the elected amount to an amount no greater than the FMV of the property disposed of. 23 Included in Canada, Department of Finance, Draft Amendments to the Income Tax Act, the Income Tax Application Rules, the Canada Pension Plan, the Children’s Special Allowances Act, the Customs Act, the Old Age Security Act, the Unemployment Insurance Act and a Related Act, April 26, 1995. 24 For a discussion of the application of section 68, see David Forster, “The Purchase and Sale of Assets of a Business: Selected Tax Aspects,” in Selected Income Tax and Goods and Services Tax Aspects of the Purchase and Sale of a Business, 1990 Corporate Management Tax Conference (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1991), 2:1-36. 25 Paragraph 111(4)(e). (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 THE CAPITAL COST ALLOWANCE SYSTEM 1253 acquisition of a depreciable property, subsection 13(7.1) applies to reduce the capital cost of the property by the amount received. Where a portion of the government assistance is repaid before the disposition of the property, the repaid amount is added to the capital cost of the property. • Where an inducement or reimbursement is received in relation to the acquisition of a depreciable property, an election under subsection 13(7.4) can be made to reduce the capital cost of the related property provided that it was acquired in the year, one of the immediately three preceding years, or the immediately following year. In the absence of this election, the amount received would be included in income pursuant to paragraph 12(1)(x). Where a portion of an inducement or reimbursement in respect of which an election has been made has been repaid before the disposition of the related property, the repaid amount is added to the capital cost of the property. • Where a taxpayer has acquired property as a replacement for certain involuntary dispositions or in respect of the disposition of a former business property, the taxpayer may, in some circumstances, elect to defer the recognition of the recapture of CCA. Where such an election is made, the capital cost of the replacement property is reduced by the amount of the deferred recapture.26 • Where a property that was acquired for some other purpose begins to be used for the purpose of gaining or producing income, the taxpayer is deemed to have disposed of and reacquired the property at the time of the change in use. The capital cost of the reacquired property will be the FMV of the property at that time unless the FMV exceeds its original cost. In that case, the capital cost will be limited to its original cost plus three-quarters of the realized gain on the deemed disposition.27 Similarly, where a property has been partially used for business and partially used for other purposes and the proportion of business use changes, there will be a deemed acquisition or disposition.28 • For passenger vehicles acquired after June 17, 1987, paragraph 13(7)(g) restricts the capital cost to a prescribed amount. The prescribed amount is currently $24,000 plus the applicable federal and provincial sales tax on $24,000.29 • Under proposed legislation,30 the capital cost of a film or videotape acquired after February 22, 1994 is reduced by the amount of any outstanding loan that is convertible into an interest in the film or videotape or the partnership that owns the film or videotape. 26 Subsections 13(4) and (4.1). 13(7)(b). 28 Paragraph 13(7)(a). 29 Regulation 7307. 30 Draft regulation 1100(21)(e) was released on September 27, 1994. See Canada, Department of Finance, Release, no. 94-084, September 27, 1994. 27 Paragraph (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1254 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE Recapture Proceeds of disposition of a depreciable property up to its cost reduce the applicable CCA class balance. If, as a result of this and other adjustments, a negative UCC balance in a class arises at the end of a taxation year, it must be added to the taxpayer’s income for the year as recaptured depreciation.31 In effect, recaptured depreciation can apply only to capital cost allowance previously claimed and not to a realization of an amount in excess of the original cost of the property. Any proceeds of disposition in excess of the original cost of a property are treated as a capital gain.32 Terminal Losses Where all of the assets of a particular class have been disposed of, subsection 20(16) provides for a mandatory deduction equal to the remaining UCC balance, referred to as a terminal loss. There are a number of provisions that may affect the recognition of a terminal loss: • Subsection 13(21.1) may apply in the case of a sale of land and building to reduce any terminal loss on the building.33 • Each passenger vehicle having a cost in excess of the prescribed amount must be included in a separate class (10.1). A terminal loss will be denied by subsection 20(16.1) when the vehicle is sold.34 • Under existing legislation, subsection 85(5.1) denies a terminal loss that would otherwise be realized on disposition of an asset to a non-arm’slength party. The terminal loss is deferred and realized by the transferee on sale of the asset. Under proposed subsection 13(21.2), where there has been an asset transfer to an affiliated party after April 26, 1995 (defined in proposed section 251.1),35 the portion of the UCC in excess of the FMV of the asset will remain with the transferor, who will continue to claim CCA until such time as the loss asset is sold outside the affiliated group. At that time, a terminal loss could be available to the original transferor. • Subsection 111(5.1) provides for the recognition of any inherent terminal loss immediately before an acquisition of control by requiring a taxpayer to deduct as CCA claimed in the year, an amount equal to the excess of the UCC of the particular class over the FMV of the property in the particular class. 31 Subsection 13(1). 39(1)(a). 33 Subsection 13(21.1) requires the use of a rather involved calculation. See the explanation in paragraphs 9 to 16 of Interpretation Bulletin IT-220R2, “Capital Cost Allowance—Proceeds of Disposition of Depreciable Property,” May 25, 1990. 34 However, where an automobile included in class 10.1 at the beginning of the year is sold, the taxpayer is allowed by regulation 1100(2.5) to claim CCA at the rate of 15 percent rate on the vehicle. 35 Included in the April 26, 1995 draft amendments, supra footnote 23. 32 Paragraph (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 THE CAPITAL COST ALLOWANCE SYSTEM 1255 Separate Classes The establishment of a separate class for a property or a group of properties affects the timing of the recognition of terminal losses and recapture. There are a number of circumstances in which separate classes are required or in which a taxpayer can elect to use separate classes. Separate classes are required by regulation 1101 where the taxpayer is carrying on separate businesses, for rental properties acquired after 1972 with a cost in excess of $50,000, passenger vehicles costing in excess of a prescribed amount, certified productions, and specified leasing properties. A taxpayer may also elect to have separate classes for certain properties, including properties that are exempt properties for the purposes of the specified leasing property rules (regulation 1101(5o)), outdoor advertising signs (regulation 1101(5l)), and rapidly depreciating electronic equipment (regulation 1101(5q)). Restrictions on CCA Claims The amount of the CCA claim allowed is subject to a number of restrictions, discussed below. Short Taxation Years Regulation 1100(3) limits the CCA allowed for short taxation years to the prorated portion (based on number of days in the taxation year divided by 365) of the CCA otherwise calculated in accordance with the regulations. Half-Year Rule The “half-year rule” in regulation 1100(2), effective from November 13, 1981, restricts the CCA claim allowed on net acquisitions (consisting of additions for the year less the lesser of original cost and proceeds of disposition for the year) in the year to one-half of the normal claim. Before the introduction of this rule, depreciable property could be acquired at or near the end of the year and a full year’s claim made. The half-year rule has the effect of arbitrarily fixing the date of all acquisitions at the middle of the taxation year. There are a number of exclusions from the half-year rule, including specified leasing property (described below), certain class 10 and 12 assets, and assets in classes 13, 14, 15, 23, 24, 27, 29, and 34. Regulation 1100(2.2) also excludes from the half-year rule depreciable property acquired in certain non-arm’s-length transactions and corporate reorganizations, provided that the transferred property was originally acquired by the transferor at least 364 days before the end of the taxation year of the taxpayer acquiring the property. 36 36 For further discussion of the half-year rule, see “An Analysis of the November 1981 Budget Proposals and Draft Regulations Relating to Depreciable Property,” in Report of Proceedings of the Thirty-Fourth Tax Conference, 1982 Conference Report (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1983), 247-67. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1256 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE Rental Property Regulation 1100(11) was introduced to limit the CCA claimed on a “rental property” to the amount of rental income earned by the taxpayer either directly or indirectly through a partnership. Where a taxpayer owns more than one rental property, the restrictions are not applied to each individual rental property but to the aggregate of the CCA claims on all rental properties. A “rental property” is defined in regulation 1100(14) to be, in general terms, a building or leasehold interest used for the purposes of gaining or producing gross revenue that is rent. These rules were introduced to prevent taxpayers who owned rental properties from sheltering nonrental income by using CCA to create or increase a loss on a rental property. Regulation 1100(12) provides that regulation 1100(11) will not apply if the taxpayer is, throughout the year, a life insurance corporation or a corporation whose principal business was the leasing, rental, development, or sale, or any combination thereof, of real property owned by it. It also excludes a partnership, if every partner is a corporation fitting this description.37 Leasing Property The restrictions on CCA in respect of “leasing property” were introduced to apply to acquisitions of property after May 25, 1976. These rules, which are summarized in regulations 1100(15) to (19), provide that the total CCA claim made by the lessor in respect of all leasing property cannot exceed the lessor’s total leasing income. “Leasing property” is defined in regulation 1100(16) to be, in general, depreciable property other than rental property that is used principally for the purpose of earning rent, royalty, or leasing income. These rules were introduced to prevent taxpayers who were in a non-tax-paying position from structuring asset acquisitions as leasing arrangements and trading off the CCA claims to the lessor in exchange for lower financing costs.38 An exception is provided in regulation 1100(16) for corporations whose principal business is the renting or leasing of leasing property, either on its own or in combination with the selling or servicing of that type of property, provided that the gross revenue from that principal business is at least 90 percent of the gross revenue of the corporation. The exclusion also applies to partnerships where each member of the partnership is a corporation that fits the same description.39 37 The rental property restrictions are discussed in detail in Interpretation Bulletin IT-195R4, “Rental Property—Capital Cost Allowance Restrictions,” September 6, 1991; and Interpretation Bulletin IT-371, “Rental Property—Meaning of Principal Business,” April 25, 1977. 38 1976 Budget, Budget Paper C, supra footnote 2, at 25. 39 The restrictions on leasing property are discussed further in Interpretation Bulletin IT-443, “Leasing Property—Capital Cost Allowance Restrictions,” March 14, 1980. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 THE CAPITAL COST ALLOWANCE SYSTEM 1257 Specified Leasing Property Despite the introduction of the 1976 limitation in respect of leasing property, the Department of Finance was of the view that further restrictions were required.40 The rules contained in regulations 1100(1.1) and (1.2) are effective for leases entered into after April 26, 1989. The rules limit the CCA claim to the amount that would have been a repayment of principal had the lease been a loan and had the lease payments been blended payments, consisting of principal and interest. The notional principal repayment is determined by first calculating the notional interest in accordance with regulation 4302. The lessee is not affected by these regulations. Each specified leasing property is required to be placed in a separate class. The rules are not intended to apply to property that is commonly leased for operational purposes and for which CCA reasonably approximates actual depreciation.41 Excluded from the definition of “specified leasing property”42 are “exempt property”43 (consisting of computers, office equipment, and furniture, having a value of up to $1 million each, buildings, automobiles, and light trucks), short-term leases of one year or less, and leases of property with an FMV of less than $25,000. Also introduced was an election that could be made by the lessee. Pursuant to section 16.1, the lessee can elect to deduct CCA and interest instead of the lease payments. Although a joint election is required, there is no effect on the lessor. As a result, it is possible for both the lessee and the lessor to be claiming CCA on the same asset.44 ASSESSMENT OF THE CURRENT CCA SYSTEM What are the strengths and weaknesses of the current CCA system? While there are many possible ways to consider this question, the following four issues are perhaps the most significant: 1) Is the system fair? 2) Is the system simple? 3) Are the rates adequate? 4) Is our system competitive with that of other countries? 40 See Canada, Department of Finance, 1989 Budget, Budget Papers, April 27, 1989, 44-46. 41 Ibid. 42 Regulation 1100(1.11). 43 Regulation 1100(1.13). 44 The specified leasing property rules have been reviewed in detail in Thomas S. Gillespie, “Lease Financing: An Update,” in Report of Proceedings of the Forty-First Tax Conference, 1989 Conference Report (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1990), 24:1-35; and Gillespie, supra footnote 14. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1258 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE Fairness In order to be fair, a tax system should, to the extent possible, treat all taxpayers equally without giving any particular taxpayer or group of taxpayers an unfair advantage. It is important that taxpayers believe that the system is fair. The perceived inequity of the depreciation system under the IWTA was a key reason for the establishment of the CCA system. As the government adjusted CCA rates over the years to aid in the achievement of certain fiscal goals and to create an incentive for business to make new investments (through, for example, an accelerated writeoff for manufacturing assets and Canadian certified feature films), tax preferences were created which gave some industries advantages over others. Many of the changes to the CCA system since its introduction (see table 1) were intended to make the system fairer for all taxpayers. For example, under the 1987 tax reform, the Department of Finance attempted to level the tax playing field by broadening the tax base and eliminating tax preferences such as accelerated writeoffs for certain assets that favoured one particular industry over another. As well as unintended advantages, the tax system for depreciable asset purchases and sales has, in some circumstances, created unintended hardship for some taxpayers. The government has attempted to alleviate hardship by making certain elections available under the Act, including the following: • An election under subsection 13(4) to designate a property as a replacement property for another property (former property) that has been disposed of in order to defer certain gains on the disposition of the former property. • Elections for assets to be included in separate classes. These have been discussed above under the heading “Separate Classes.” • An election to transfer assets from one class to another. As a result of the many changes in the prescribed classes for a given type of property, it is possible that upon disposition of an asset in an old class, recapture could occur because a newly acquired property was included in a different class. In order to alleviate this burden, regulation 1103(2)(d) allows the taxpayer to elect, in the year of disposition of the former property, to transfer the former property to the same class as the new property just before the disposition of the property. In this way, recapture can be deferred. In addition, regulation 1103 provides for a number of other specific transfers between classes under various circumstances. Simplicity Ideally, a tax system should be simple, straightforward, and easy to administer by both the taxpayer and the tax authorities. The basic method of calculating CCA remains straightforward. The familiar T2S(8) schedule attached to corporate tax returns, and similar schedules for individuals and trusts, have not required substantial change over the years. However, (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 THE CAPITAL COST ALLOWANCE SYSTEM 1259 the system changes and the myriad of different classes and rates have resulted in a system that is considerably more complicated than the one introduced in 1949. As in other areas of the Act, there has been a tradeoff between fairness and simplicity. It can be argued, however, that fairness within the tax system, which is the more important goal, has required increasing complexity throughout the Act and that the CCA system is a major example (and rightly so) of this. Therefore, it is quite acceptable that, in an effort to make the system fairer to and among taxpayers, to deal with the increasing complexity of business itself, and to stop any inappropriate drain on tax revenues, some of the original simplicity of the system has had to be sacrificed. Adequacy of the Rates A comparison of accounting depreciation and tax depreciation provides a good initial indicator of the adequacy of the CCA rates. The purpose of accounting depreciation is to allocate the cost of a capital asset to those accounting periods that benefit from its use in order to provide a matching of revenues and expenses. The method and rate of accounting depreciation chosen generally reflect the expectations for the asset regarding factors such as its estimated economic life, the decline in its use and operating efficiency, obsolescence, and changes in revenue-producing ability. Therefore, as long as the annual CCA allowed to a taxpayer is at least equal to the annual accounting depreciation, one could perhaps conclude that the CCA system is at least adequate to allow the taxpayer to recognize the cost of property over its useful life. While there are a number of different accounting depreciation methods (straightline, declining balance, sum of the year’s digits), the straightline method, which allocates the estimated cost less salvage value of the asset over the estimated years of useful life, is the most common method used by most large corporations. For smaller companies, the declining balance method is often used, so that accounting depreciation and tax depreciation are the same.45 Before the 1987 tax reform, CCA rates were, in many cases, far in excess of accounting depreciation rates. At that time, the government estimated that the cost of allowing for CCA rates in excess of accounting depreciation was $2.3 billion in 1980 alone.46 One of the goals of the 1987 tax reform was to reduce the accelerated CCA rates so that they would be closer to accounting rates. A comparison between tax and accounting rates is complicated by the fact that accounting rates for the same property can vary among different businesses, depending on the particular fact situation. The example in table 3 compares the tax and accounting depreciation for manufacturing 45 1976 Budget, Budget Paper C, supra footnote 2, at 8. Department of Finance, 1985 Budget, The Corporation Income Tax System: A Direction for Change, May 23, 1985, 9. 46 Canada, (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1260 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE Table 3 Comparison of Tax and Accounting Depreciation on Manufacturing and Processing Equipmenta Year 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Original cost . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Depreciation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Undepreciated cost . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Depreciation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Undepreciated cost . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Depreciation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Undepreciated cost . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Depreciation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Undepreciated cost . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Depreciation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Undepreciated cost . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Depreciation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Undepreciated cost . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Depreciation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Undepreciated cost . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Depreciation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Undepreciated cost . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Depreciation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Undepreciated cost . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Taxb Accountingc Difference 10,000 (1,500) 8,500 (2,550) 5,950 (1,785) 4,165 (1,250) 2,915 (875) 2,040 (612) 1,428 (428) 1,000 (300) 700 (210) 490 10,000 (625) 9,375 (1,250) 8,125 (1,250) 6,875 (1,250) 5,625 (1,250) 4,375 (1,250) 3,125 (1,250) 1,875 (1,250) 625 (625) 0 0 875 875 1,300 2,175 535 2,710 0 2,710 (375) 2,335 (638) 1,697 (822) 875 (950) (75) (415) 490 a Manufacturing and processing equipment acquired in 1995 half-way through the year, at a cost of $10,000. b Assumed to be included in class 43 with a CCA rate of 30%. c Assumed to be depreciated on a straightline basis over eight years. and processing equipment with a cost of $10,000. The example illustrates that CCA is generally higher in the early years of an asset’s life, owing to the use of the declining balance method, and that accounting depreciation is higher in the later years. The straightline method allows for the full depreciation of the asset over its estimated useful life, whereas the declining balance method extends depreciation over a longer period. In this situation, the “annual crossover point” (the point at which annual accounting depreciation exceeds annual CCA) is in year 5 and the “cumulative crossover point” (the point at which total accounting depreciation exceeds total CCA) is in year 8. Table 4 shows this comparison for manufacturing and other major depreciable assets. In all five categories, annual CCA claims exceed accounting depreciation for the initial years, and cumulative CCA does not exceed cumulative accounting depreciation until the later part of the asset’s estimated useful life. This implies that the tax system still contains a reasonable incentive for taxpayers to make capital expenditures. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 THE CAPITAL COST ALLOWANCE SYSTEM Table 4 1261 Summary of Crossover Points for Tax and Accounting Depreciation Asset category Manufacturing assets . . . . . Buildings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Furniture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Computer software . . . . . . . Automobiles . . . . . . . . . . . . CCA rate Accounting depreciation ratea Annual crossover yearb Cumulative crossover yearc 30% DB 4% DB 20% DB 100% 30% DB 8 years SL 40 years SL 7 years SL 3 years SL 5 years SL year 5 year 13 year 4 year 3 year 3 year 8 year 27 year 5 year 4d year 5 DB: declining balance SL: straightline a Assumed to be a typical accounting depreciation rate. Actual rates for each asset category will vary among different businesses. b The annual crossover year is the year in which the annual accounting depreciation exceeds annual CCA. c The cumulative crossover year is the year in which cumulative accounting depreciations exceed cumulative CCA claims. d Accounting depreciation is prorated in the year of acquisition. Since it is assumed that the asset is acquired halfway through year 1, the property will not be fully depreciated until year 4. Competitiveness The competitiveness of Canada’s tax system is an increasingly important issue, given the trend toward a global economy with few trade barriers. As the competition to Canadian business most often comes from the United States, the tax depreciation systems of the two countries should be compared. The modified accelerated cost recovery system ( MACRS) is the method of depreciation used in the United States for most tangible property placed in service after 1986. Under MACRS, the cost of eligible property is recovered over a period of 3, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20, 27.5, 31.5, or 39 years, depending upon the type of property (see table 5 for examples).47 MACRS depreciation tables may be used to compute depreciation over the recovery period.48 These tables incorporate the appropriate recovery period and the switch from the declining balance method (generally 200 percent) to the straightline method in the year in which the straightline method provides a depreciation allowance equal to, or greater than, the declining balance method. This ensures that the full cost is depreciated over the recovery period, rather than an indefinite declining depreciation amount as under the Canadian system. Similar to the CCA system in Canada, tax depreciation is limited to one-half normal depreciation in the first year of service. A comparison with the UK system also is of interest. In the United Kingdom, the method of calculation is quite similar to that used in Canada: 47 Rev. 48 Rev. proc. 87-56, 1987-2 CB 674; and Rev. proc. 88-22, 1988-1 CB 785. proc. 87-57, 1987-2 CB 687; and Rev. proc. 89-15, 1989-1 CB 816. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1262 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE Table 5 Summary of Canadian, US, and UK Depreciation Rates Asset category Commercial buildings . . . . . . . . Manufacturing assets . . . . . . . . . Autos and light trucks . . . . . . . . R & D equipment . . . . . . . . . . . . Furniture and fixtures . . . . . . . . . Computer hardware . . . . . . . . . . Patents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Computer software . . . . . . . . . . . Canadaa 4% DB 30% DB 30% DB 100% 20% DB 30% DB SL over life or 25% DB 30% DB or 100% Depreciation rates USa UKb 39 years SL 5, 7, or 10 years c DDB 5 years DDB 5, 7, or 10 years DDBe 7 years DDB 5 years DDB 15 years SL 4% SL 25% DB 25% DBd 100% 25% DB 25% DB 25% DB 3 years SL 25% DB DB: declining balance DDB: double declining balance SL: straightline a Claim in year of acquisition generally limited to 50%. b No half-year rule in year of acquisition. c Writeoff rate is determined by type of business. d Where the cost of the property exceeds £12,000, the capital allowance is limited to £3,000/year until tax writtendown value falls below £12,000. e Writeoff rate is determined by type of equipment. capital allowances are calculated using either the declining balance or the straightline method. The United Kingdom does not have a half-year rule and has fewer asset classifications. Examples of the current UK rates are summarized in table 5.49 The data presented in table 5 may suggest some preliminary conclusions about the relative competitiveness of Canada’s CCA system. The US rates generally are more generous than the Canadian rates since, for many assets, the United States uses the double declining balance basis of calculating depreciation; the Canadian rates, in turn, are for the most part a little more generous than the UK rates. However, a comparison of rates alone is not a particularly useful approach. Meaningful comparisons of tax depreciation systems in different countries cannot be made without consideration of other key factors as well, such as tax rates and time value discount rates. One possible approach is to approximate the present value of the “tax shield” (tax saved from depreciation writeoffs) for the same property in each jurisdiction. Table 6 presents a comparison of the tax shield provided by the tax depreciation systems in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom for selected types of assets, each with an assumed cost of $10,000. This calculation, which assumes a discount rate of 8 percent, takes into consideration both the writeoff rates and the corporate tax rates. The table includes the tax shield for both a manufacturer and a non-manufacturer since the Canadian tax rates applicable to each differ significantly. 49 Capital Allowances Act 1990, Public General Acts of 1990, c. 1. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 THE CAPITAL COST ALLOWANCE SYSTEM 1263 Table 6 Comparison of Present Value of Tax Shield Provided by the Canadian, US, and UK Tax Depreciation Systems Present value of tax shield:a manufacturer USc UKd Asset Canadab Manufacturing assets . . . . . . . . . . . Commercial building . . . . . . . . . . . Furniture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Computer software . . . . . . . . . . . . . Automobiles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2,705 2,816e 2,500 1,142 1,124 1,409 2,447 2,612 2,500 3,172 3,061 2,500 2,705 3,002 2,500 Present value of tax shield:a non-manufacturer Canadaf USc UKd Commercial building . . . . . . . . . . . Furniture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Computer software . . . . . . . . . . . . . Automobiles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,431 3,066 3,975 3,389 1,124 2,612 3,061 3,002 1,409 2,500 2,500 2,500 a Calculated on an asset with a cost of $10,000 using a discount rate of 8%. Assumes that the taxpayer is in a taxable position in all years. b Assumed tax rate of 35.58%. c Assumed tax rate of 37%. d Assumed tax rate of 33%. e Average of present value for manufacturing assets eligible for 5-year, 7-year, and 10-year writeoffs. f Assumed tax rate of 44.58%. While it is still difficult to draw firm conclusions from such broad-based data, it appears that the Canadian CCA system measures up well to the depreciation systems in the United States and the United Kingdom in terms of tax relief provided for new capital expenditures. However, this is because Canadian tax rates are higher than the rates for the United States and the United Kingdom, particularly for non-manufacturers. If tax rates are ignored, the depreciation rates under the Canadian system are generally less favourable than the US rates and comparable to those in the United Kingdom. The detailed results in table 6 show that, in the case of the manufacturer, the tax shields for the United States and Canada are quite similar. The tax shield in the United States is marginally higher than the tax shield in Canada for assets other than computer software and buildings. The tax shield provided by the UK writeoff is lower than that in Canada for all assets other than buildings and furniture. In the case of the non-manufacturer, the present value of the tax shield provided by the Canadian system is higher than both the US and the UK tax shields in all cases. This is a result of the high effective tax rate (44.58 percent) for a Canadian taxpayer that is not eligible for the small business deduction or the reduced manufacturing tax rates. The CCA system is, of course, only one factor in determining the competitiveness of Canada’s tax system for capital asset acquisitions. Other factors include the effective tax rate, the availability of investment tax credits, tax-free holiday periods, the treatment of tax losses, corporate minimum taxes, and capital taxes. For this reason, studies undertaken to compare various tax systems have generally considered a number of these (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1264 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE factors together and not just CCA rates in isolation. These studies have concluded that Canada’s tax depreciation system is less generous than that of the United States.50 THE FUTURE OF THE CCA SYSTEM Overall, the CCA system in place today seems to be operating well, although some would debate whether the rates of writeoff take full account of obsolescence rates caused by the rapidly accelerating changes in business in the 1990s. The basic system introduced in 1949 has survived a number of tax reforms, but it has become significantly more complex. The main changes, other than changes in rates, have been the restriction of claims in certain circumstances, so as to improve the fairness of the system, and the elimination of improper results and perceived abuses. What lies ahead? We are unlikely to see dramatic changes to the current CCA system, since the government is likely to follow the maxim “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” With this in mind, business and government should work to ensure that the CCA system, and particularly the rates, are subject to regular review. This review is essential to help keep Canada’s tax system competitive in the increasingly globalized, freer trading economy and to ensure that changes to actual obsolescence rates are recognized by the CCA system in a timely manner. Against this objective, it is recognized that, while accelerated CCA writeoffs were often used as a fiscal policy tool in past decades, the current debt and deficit burdens of the federal and provincial governments make it probable that policy makers will be reluctant to apply this approach for the remainder of the 1990s and well into the first decade of the 21st century. 50 See, for example, Jack M. Mintz and Thomas Tsiopoulos, “Contrasting Corporate Tax Policies: Canada and Taiwan” (1992), vol. 40, no. 4 Canadian Tax Journal 902-17, which compares the competitiveness of the Canadian tax system using the cost of capital. The cost of capital is defined to be the minimum rate of return that an investment must earn to cover the operating costs associated with that investment. The cost of capital takes into account the corporate tax rate, the present value of depreciation allowances for tax, the valuation of inventory, and the deductibility of interest. Also see Jack M. Mintz, “Competitiveness and Tax Policy: How Does Canada Play the Game?” in the 1991 Conference Report, supra footnote 15, 5:1-14. In the latter study, the author calculates the effective tax rate on capital invested in a marginal project, taking into account federal and provincial corporate and capital taxes. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5