Creativity, School Ethos and the Creative Partnerships programme

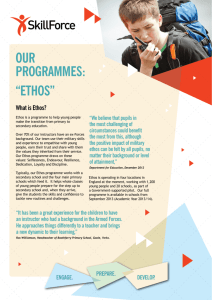

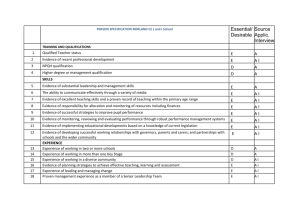

advertisement