non social play CD 1982

advertisement

Nonsocial Play in Preschoolers: Necessarily Evil?

Kameth H. Rubin

University of Waterloo

RUBIN, KENNETH H Nonsocial Flay in Preschoolers Necessarily Evil? CHILD DEVELOPMENT,

1982, 53, 651-657 It has been suggested that children who play on their own, without interacting with peers, may be at nsk for social, cognitive, and social-cognitive problems Recently,

however, the children's play hterature has revealed that some forms of nonsocial activity are

constructive and adaptive In this study the social, cognitive, and social-cogmtive correlates

of nonsocial play were examined 122 4-year-olds were observed for 20 mm dunng free play

They were also administered a role-takmg test and tests of social and impersonal problemsolvmg skills Sociometiic popvdanty and social competence (as rated by teachers) were also

assessed Analyses indicated that nonsocial-functional (sensonmotor) and dramatic activities

generally correlated negatively with the measures of competence Parallel-constructive activities

generally correlated positively with the various measures of competence

In recent years, it has been suggested that

children who play on their own, vwthout frequently interacting with peers, may be at nsk

for later social and social-cognitive problems

These suggesfaons stem from both theoretical

and empirical sources Theoretically, Piaget

(1926, 1932), in his early work, noted that the

reciprocal nature of peer relations and the inevitable social conflicts concemmg diflFenng

viewpoints in early childhood promoted the development of moral judgmental, discursive, and

perspective-taking skills (see Rubm & Everett

[m press] for a recent review of this hterature)

From non-Piagetian perspectives, peers have

been thought to serve as social leammg models

and as social remforcers m the development of

social and cognitive skiBs (Allen 1976, Combs

& Slaby 1978, Hartup 1979) Given these theoretical perspecbves, developmentalists have recently predicted negative outcomes for children

who have had madequate peer mteractive experiences

Indirect empincal support for these theoretical positions emanates from the hterature

concerning sociometnc measures of peer acceptance Poor sociometnc ratings m early and

middle childhood have been shovwi to predict

later social, educational, and mental health

problems (Cowen, Pederson, Babigian, Izzo, &

Trost 1973, Ro£F, Sells, & Golden 1972, Ullman

1957) However, direct support for the theoretical positions has been nuxed, at best At present, there is a notable lack of data to suggest

that low rates of peer mterachon m early childhood either predict or concurrently relate with

indices of soaal and social-cogmtive competence (Asher, Markell, & Hymel 1981) Moreover, low rates of peer interaction m early childhood have been found to correlate negatively

with peer populanty m some studies ( e g ,

Goldman, Corsmi, & deUnoste 1980) but not

m others ( e g , Gottman 1977)

One possible explanation for the general

lack of data supportive of the position that nonsocial activity correlates negatively with mdices

of social competence emanates from the observational hterature concemmg children's play

Rubm and his colleagues (Rubm, Maiom, &

Homung 1976, Rubin, Watson, & Jambor 1978)

have indicated that between 402 and 60% of the

nonsocial activity of presdiool- and kmdergarten-aged children is constructive or educational

in nature Given these data, it may be that the

earlier reported correlations between nonsocial

behavior and measures of populanty and social

competence were somewhat obscured by mclusion of particular adaptive cognitive forms of

play within the nonsocial categoncal system

From this perspective it is conceivable that

some forms of nonsocial activity are concur-

This research was supported by a grant from the Ontano Mental Health Foimdation and

the Ontano Ministiy of Commumty and^ Social Services An abbreviated version of this article

was presented at the Bienmal Meetme of the Society for Research m Child Development,

Apnl 1981, Boston I would Uce to thadc Judy Midde for her help in the collection and codmg

of^the data Special thanks are also given to the teachers and children m the Regional Mumcipahty of Waterloo who graciously made their time available to me Requests for repnnts

should be sent to Kenneth H Rubm, Department of Psychology, Umversity of Waterloo,

Waterloo, Ontano, N2L 3G1

\PluU Devdepmtnt, 1982, S3, 651-657 ® 1982 by the Soaety for Reseaicfa in Child Development, Inc

All nghta reserved 0009-392O/82/53O3-0O22$OI 00)

652

Child Development

rently predicbve of developmental lag whereas

others are equally predictive of posibve adaptation Such a suggestion would be in keeping

with the Asher et al (1981) posibon that the

simple use of rate of nonsocial acbvity to identify children at nsk would be less mentonous

than the use of a quahtative assessment of nonsocial behavior for identification purposes

The purpose of this study was simply to

identify those forms of nonsocial play m 4-yearolds which correlate either positively or negabvely with assessments of competence m the

social, social-cognitive, and cognitive domains

In particular, it was hypothesized that the incidence of nonsocial-funcbonal (or sensonmotor) play, that is, repetibve muscle movements

with or without objects (Smilansky 1968), because of its relatively low cognibve play status

for 4-year-olds (Rubin, Fem, & Vandenberg, in

press), would correlate negabvely with markers

of soaal, social-cogmbve, and cognitive development Similarly, since most dramabc or fantasy play of 4-year-olds is earned out in small

groups (Rubin et al, m press), it was predicted that the incidence of the sociaDy less

mature form of dramabc activity (i e , nonsocial-dramatic play) would correlate negatively

with assessments of social, social-cognibve, and

cognibve development Construcbve play ( e g ,

artwork and puzzle and block construcbon) is

often earned out most proficiently when alone

Moreover, this adaptive behavior is the most

frequent form of play generally observed m

preschool settmgs (Rubin et al, m press)

Given this {)erspecbve, it was predicted that

the incidence of nonsocial forms of constructive

pky would correlate positively with the latter

measures of competence Fmally, it was predicted that the madence of unoccupied and onlooker behavior, two of Farten's (1932) least

mature forms of social parbcipation, would correlate negabvely with assessments of social, social-cognibve, and cognibve development

Method

Subjects

Fifty-three male and 69 female 4-year-olds

(M = 58 11 months, SD = 4 37 months) who

attended preschools or day-care centers m a

southwestern Ontario community served as subjects in this study Familial socioeconomic status ranged from lower-middle to upper-middle

class

Instruments and Procedures

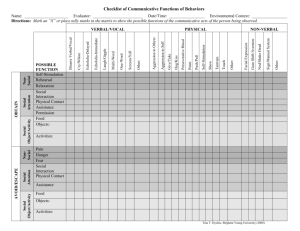

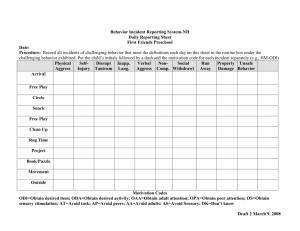

Behavtoral observations—Each child was

observed for a total of 30 min dunng free play

following procedures similar to those described

m Rubm et al (1976, 1978) Basically, each

child was observed for six 10-sec bme intervals

each day over a 30-day penod Behaviors were

coded on a checklist which included the cogmtive play categories of Smilansky (1968), tiiat

IS, functional-sensonmotor, construcbve, and

dramabc play and games with rules The cognitive play categones were nested withm the

social participabon categones earber descnbed

m Parten (1932), that is, sobtary, parallel, and

group activities Thus, for example, if a given

child was observed to construct a puzzle m

close proxirmty but not with another child, the

activity was coded as parallel constructive

Other observabonal categones included unoccupied behavior, onlooker behavior, reading or

being read to, rough-and-tumble play, exploration, acbve conversabons with teachers or peers,

and transitional (moving from one acbvity to

another) activities

After coding the child's play behavior, the

observer noted the names of the focal child's

play or conversational partners and who it was

that lnibated the group activity FoUowmg Furman, Rahe, and Hartup (1979), the affecbve

quahty of each social interchange was coded as

positive, neutral, or negative

Four observers recorded the children's

play behaviors Each observer was tramed by

using videotapes and observmg children's play

in a laboratory preschool not employed m the

present study Rehabihty was assessed by pairing each observer with every other observer for

a total of 30 mm of observational coding each

The number of coding agreements/ (number of

agreements -f- disagreements) exceeded 85% m

each case

Soctometrtc populartty—The sociometnc

rating scale recently developed by Asher, Singleton, Tinsley, and Hymel (1979) was employed in this study Each child was mdividually presented with color Polaroid photographs

of each of his or her classmates The cmldren

were asked to assign each picture to one of

three boxes on which there was drawn either a

happy face ("children you hke a lot"), a neutral

face ("children you kmda hke"), or a sad face

("children you don't hke") As m Asher et al

(1979), cluldren thus received a number of

positive, negative, and neutral rabngs Posibve

ratmgs were accorded a score of 3, neutral

ratings a score of 2, and negative ratings a score

of 1 Each child received one total rabng score

Since the numbers of children m each of the

eight classrooms vaned, the rabng score re-

Kenneth H. Rubin

ceived by each child was divided by the number of children m each class who were given

the sociometnc test

Social-competence —Two teachers m each

of the classrooms were given the Behar and

Stnngfield (1974) Preschool Behavior Questionnaire (PBQ) to fill out High scores on the

PBQ are suggestive of social maladjustment

The teacher ratings m each class were averaged

for each child

Role taktng and social problem solving —

Cognitive role-takmg skill was measured by admmistenng the DeVnes (1970) "hide the penny" game to each child The expenmenter and

child took turns hiding a coin m one of his or

her hands Each child was scored according to

the recursive thought cntena described by DeVnes The maximum score was 10

Social problem-solving skill was assessed

by admmistermg an elaborated version of Spivack and Shure's (1974) Preschool Interpersonal Problem-Solving (PIPS) test to each child

The Social Problem-Solvmg Task (SPST) was

designed to assess both quantitative and qualitative features of social problem solving In general, each child was presented with a senes of

eight pictured problem situations m which one

story character wants to play with a toy or use

some matenal that another child has in his or

her possession The child was asked what the

central character in the story could do or say

so that she or he could gam access to the toy or

matenal The characters m the story vaned with

regard to either age (same vs different age

characters), sex (same vs different sex characters), and race (same vs cross-sex characters)

For example, with regard to the three agerelated picture stones, in one case two 4-yearold, same-sex, same-race characters were portrayed In a second picture, sex and race were

held constant, and trie subject was told that a

4-year-old wanted to play with an object in the

possession of a 6-year-ola In the third case, the

4-year-old wanted a toy being played with by

a 2-year-old Similar covanations occurred for

the sex and race of the story characters Detailed examples of the stones may be obtamed

from the author

After presentation of each picture and the

assoaated story* the child was asked to tell the

expenmenter everything that the central character could do or say so that she or he could

obtain the desired object As m the PIPS (Spi-

653

vack & Shure 1974) the number of relevant alternatives was computed

Impersonal problem solving —^An elaboration of Smith and Dutton's (1979) lure retneval problem was administered to each child

An extended descnpbon is found m Cheyne

and Rubin (Note 1) Each child was seated

at a low table on which was placed a set of

sticks and blocks Each set consisted of three

24-cm, three 15-cm, and three 6-cm sbcks and

five blocks with four holes The expenmenter

pointed out that the sbcks were of different

lengths and demonstrated the mserbon of a

stick into one of the holes m a block The child

was allowed to play with these materials for 8

mm Durmg this penod, the expenmenter kept

a conbnuous record of the child's play constructions and his or her verbahzabons Constructions were coded as simple, moderate, or complex (Cheyne & Rubin, Note 1), and the number of each type of construction was noted

From these observations a measure of configural complexity was computed by subbactmg

the number of simple constructions from the

number of moderate plus complex construcbons

(Cheyne & Rubin, Note 1) The number of fantasy ( e g , rocket ships, people) construcbons

was also recorded Following this penod, all

children were immediately presented with six

sticks (two of each length), a block, and the

problem of retnevmg a marble enclosed m a

transparent box placed at a distance from the

child The solubon mvolved the joining of the

two longest sticks by means of the block, releasing a latch on the box, and raking m the

marble Although hints in the manner of Sylva

(1977) were given at approximately 1-mm mtervals (to a maximum of five hints), the major

dependent vanable for impersonal problem

solving was ttme to solution Dunng the problem-solving penod, the number of posibve selfstatements ("I can do it'") and the number of

denials ("I can't do it", "I don't wanna do it")

were also recorded

Receptive vocabulary —The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test was administered to each

child Mental age (MA) was computed

Results and DiBcussion

A correlation matnx was computed for the

vanables descnbed in the Methods secbon

Pnnciple correlations of interest herem mcluded

those with each of the nonsocial behavior cat-

1 Full descnpbons of the instruments and scormg procedures are available from the author

on request

654

Child Developinimt

egones, that is, so&iary-functional, -constmcbve,

and -dramatic play, poraZfei-functional, -constructiye, and -dramatic play, and unoccupied

and onlooker activity Those correlations which

reached (p < 05 or better, one-tailed) or approached significance are reported m table 1

Perhaps the least mature form of play produced by 4-year-olds in preschool settmgs is

that which is earned out alone and mvolyes sensorunotor, repetitive motor acbons (Rubm et

al, m press) Sohtary-functional play was found

to correlate negatively with MA, r(121) =

19, p < 02 Wrth the efiFects of MA partialed

out, the frequency of solitary-functional play

was negatively correlated with (a) the number

of social overtures received from other children,

(b) the proportion of positive interactions to

the total number of social interactions, (c) the

number of peer cwiyersations, (d) the sociometnc rating, and (e) the mdex of construction

complexity computed during the "play phase"

of the impersonal problem-solvmg paradigm It

should be noted that complexity of object construction during play is a significant predictor

of problem-solving proficiency (Cheyne & Rubin, Note 1) Taken together, these correlational data suggest that the production of a

large amount of sohtary-functional play by 4year-olds may be taken as an "at-nsk" indicator

The incidence of sohtary-constractive play

was negatively correlated with (a) the number

of social overtures received and (b) the number

of peer conversations held during free play

Given the lack of significant correlations with

either the peer sociometnc ratings or with the

teacher ratings of social competence, this category would appear to be somewhat benign and

certainly less negatively tinged than sohtaryfunctional activity

When fantasy or dramatic play occurs in

4-year-olds it is usually carried out with or near

other children That is, the "norm" for this age

group IS the production of social rather than

nonsocial dramatic play (Rubm et al, in press).

As such, solitary-dramatic play at 4 years of age

may reflect a lag m those social, cognitive, and

social-cognitive skills usually associated with

pretense activity, that is, perspective-takmg and

problem-solvmg skills Given this speculation, it

IS noteworthy that the frequency of sohtarydramatic play was negatively related with chronological age (CA) even within this restricted

age-range sample Sohtary-dramatic play was

also negatively correlated with (a) the prc^rtion of positive group interactions to the total

number of social interactions, (b) performance

on the DeVnes (1970) perspective-taking task,

(c) soaometnc status, and (d) the measure of

TABLE 1

PARTIAI. CORRELATIONS BETWEEN NONSOCIAL PLAY CATEGORIES

AND OTHER MEASURES, CONTROLLING FOH MA {N = 123)

Sol-F

Reading

Conversations

Rough and tumble

Transitional

Social initiations

received (N)

Proportion positive

interactions

Proportion neutral

interactions

Proportion negative

lnteracUons

CA

DeVnes

Soaometnc

Relevant categones

(SPST)

Complexity

Fantasy constructions

Denials

Time to solution

Teacher rating total

So!-D

Sol-C

- 11

- 48*

04

13

-

05

35*

11

02

- 30*

- 23**

P-F

PC

02

08

01

21**

09

02

P-D

On

Un

- 26**

- 02

- 10

- 07

10

- 30*

19***

06

03

- 14

- 06

- 10

- 09

11

11

- 16***

11

09

- 18***

13

- 07

13

12

11

- 05

- 09

- 18***

- 06

- 22**

- 03

- 09

06

- 07

04

21**

- 18*** - 07

- 22** - 03

- 16*** - 08

03

03

- 06

- 05

- 13

- 06

- 15***

- 15*** - 10

21***

- 23**

- 05

06

04

12

01

- 01

05

- 16*** 09

- 14

05

-

- 01

16*** _

06

16*** -

11

16***

09

01

03

03

14

- 07

15***

01

-

- 02

- 25**

- 21**

10

17*** - 12

03

i9»*»

03

11

04

- 06

- 05

01

15***

03

08

15*** - 03

- 02

10

20*** - 09

06

13

07

06

12

19***

15***

18***

18***

12

-

03

20***

10

02

-

12

26**

- 01

13

08

- 32*

NOTE —Sol — sohtaiy, P — i>anllel. On •• unoccujMed, On — onlooker, F — ftinctumil, C — comtnictive, O — dramatic

• # < 001 (fflie-Ualed)

**p< 01

***p< 05

Kenneth H. Robin

construcbon complexity made dunng the "play

phase" of the impersonal problem-solvmg task

The latter measure has been viewed as a significant precursor to the solubon of the impersonal

problem presented herein (see Cheyne & Rubm. Note 1) Sohtary-dramatic play was posibvely correlated with teacher ratmgs of social

maladjustment A positive correlabonal trend

was found with the amount of time it took to

complete the impersonal problem-solvmg task

(p < 06) Given the data above, it would appear as if the mcidence of sohtary-dramatic

play m 4-year-olds is a concurrent mdex of lack

of competence in the social, social-cognibve,

and cognibve domams For play enthusiasts, the

message may be that not all pretense acbvity

augurs well for 4-year-olds Given the correlational nature of these data, however, firm causal

statements concenung sobtary pretense cannot

be made

Parallel-funcbonal acbvity, or repebbve

motor acbvity in close proximity to others, was

found to correlate posibvely with (a) the frequency of transitional (or moving from one activity to the next) behaviors, (fc) the proportion of negabve mteracbons to the total number

of social mteracbons, and (c) the measure

of play construction complexity The picture

pamted by such acbvity is diat it involves sensonmotor, usually large-scale, frenebc motor behavior that bnngs children mto conflicts, as

evinced by the posibve correlabon with negative mteractions The posibve correlabon with

transitional activity suggests the possibility that

the two behaviors may be taken as a classroom

index of lmpulsivity Given the negabve correlation between parallel-functional play and the

construcbon of complex play figures/objects

(which appears to require planmng, reflection,

and self-regulabon), the nobon of parallel-funcbonal acbvity as a behavioral index of lmpulsivity IS not farfetched Further research would

do well to explore this postulated hnk directly

Interesbngly, neither teacher nor peer ratings of social competence or popularity were

negabvely linked to such potenbally disturbmg

behavior m the classroom It might be worthwhile to note that the correlabon between parallel-funcbonal acbvity and the number of posibve sodometnc rabngs from same-sex peers

was, m fact, moderately significant m the negabve direcbon, r(121) = — 15, p < 05 As

such, the production of parallel-funcbonal play

m 4-year-olds may very caubously be taken as

an mdicator of problemabc social development

Parallel-constnicbve behavior appears to

655

resemble those acbvities that elementary school

teachers promote m their classrooms Moreover,

it IS the most frequently occumng activity observed m prescbool setbngs (Rubm et al, m

press) Typically, the children sit m close proximity, often around the same table, and carry

out art, LEGO-block, puzzle, or other creative/

construcbve acbvibes As one might expect

from this descnpbon, teacher ratmgs erf social

maladjustment were significantly and negabvely

correlated with the frequency of parallel-constructive play (with the effects of MA parballed

out) The incidence of this acbvity was also

linked significantly and posibvely with MA

With the effects of MA parbaled out, the frequency of parallel-constnicbve play was negabvely correlated with the mcidence of roughand-tumble play and with the amount of time it

took to solve the impersonal problem Posibve

correlabons were evmced for (a) sociometnc

ratmgs, (b) the number of relevant altemabves

produced on the social problem-solvmg task,

and (c) the measure of play construcbon complexity Taken together, diese correlabonal data

suggest that children who play near but not

with others and who engage m construcbve activities are good problem solvers in both the

social and nonsocial domains Such children are

also viewed as popular among their peers and

as socially skilled by their teachers

Parallel-dramatic acbvity occurs when children take on roles in close proximity to but not

in coordinabon with their peers. Suoi uncoordinated pretense may result from the child's mabihty to take into account the various roles

and social rules ostensibly mvolved m sociodramatic activity (Garvey 1977, Rubin et al, m

press) Given this perspective, it was not surprising to find a significant negabve correlabon

between the producbon of parallel-dramabc

play and GA

Although the themes of pretense activity

were not coded m this study, it would have

been mteresbng to note whether fantasy behavior conducted near but not with others is

more likely to take on hostile/aggressive than

domesbc or less rambunctious themes Performance of such acbvity m proximity to but not

with others could serve as a safeguard m ascertaining that one's peers understand that the hostihty displayed is not meant hterally or that it

IS "just pretend " Clues about the themes of parallel-dramabc play are drawn from the posibve

correlations with teacher ratmgs of social maladjustment as well as with tiie mcidence of

rough-and-tumble play Moreover, the emission

656

C3iild Devdopment

of parallel-dramatic play was negatively correlated with positive social exchange and yet not

correlated with negative interactions Interestingly, the frequency of such dramatic activity

was correlated with the production of fantasy

objects ( e g , guns) and people durmg the

stick-block play session of the impersonal problem-solvmg task The data thus suggest that

parallel-dramatic play, although not viewed as

desirable by teacliers, may be an appropnate

medium for hostile displays m the preschool

Unoccupied behavior was positively related with teacher ratings of social maladjustment and negatively correlated with the number of peer conversations Onlooker activity

was negatively correlated with MA, r(121) =

- 18, p < 03 With the effects of MA partialed out, onlooker behavior was negatively

correlated with (a) CA, (b) the number of

peer conversations, (c) rough-and-tumble play,

(d) complexity of play constructions, and (e)

teacher ratmgs of social maladjustment In

short, the more often that children spent their

tune harmlessly observing others or looking at

objects around the room, the greater the hkelfliood that they were younger mentally and

chronologically than their counterparts who

displayed less such behavior Onlookers were

viewed also as relatively soaally competent by

then- teachers As such, onlooker behavior may

be viewed as a somewhat benign "Charhe

Brown''-type activity

The correlational analyses computed for

males and females separately did not vary significantly from those data presented above Interestmgly, the DeVnes measure of role taking

correlated negatively with sohtary-function^

play for girls, r = — 28, p < 02, but not for

boys Alternatively, this social-cognitive measure correlated negatively with onlooker behavior for boys, r = — 32, p < 03, but not for

girls These negative correlations with behavioral mdices of nonsocial play do make sense

theoretically However, the sex differences

elude convement explanation at this time No

other sex differences were found m the separate

correlational analyses

In summary, the observational data reported herem support the recent contention that

qualitative rather than quantitative dimensions

of nonsocial activity be explored when children

are targeted as "at nsk" for developmental problems (Asher et al 1981) Some nonsocial activities ( e g , sohtary-functional, sohtary-dramatic,

and parallel-functional play) do, mdeed, correlate negatively with mdices of social, soaal-

cognitive, and cogmtive skdl Other forms of

nonsocial activity ( e g , soLtary-constructive,

onlooker behaviors) are somewhat benign Parallel-constructive play IS highly predictive of

competence

To some degree, these latter data nicely

mirror those of Jennings (1975), who reported

that preschool children who show greater onentation to objects rather than people spend much

of their time constructing products m their

play, purportedly as a result of such activity,

they perform well on tests of abibty to organize

and classify physical matenals The paraDelconstnictive play correlations reported herein

support Jennmgs's findings Moreover, the present study also suggests that parallel-constructive

players perform well, not only on impersonal

problems but also on social problems Furthermore, such nonsocial activity was associated

with peer populanty and teacher ratings of social competence These data clearly indicate

that not all nonsocial activity is associated with

negative developmental prognosis Grven the

lack of an overall negative correlational picture

for nonsocial but constructive forms of play, it

would thus behoove researchers and practitioners not to denigrate all forms of nonsocial

activity Psychologists and educators who plan

preschool intervention programs to amehorate

social play "deficits" or to prevent the supposed

negative outcomes of nonsocial activity in early

childhood would do well to focus on those behaviors found to be concurrently correlated

with assessments of social, cognitive, and social-cognitive lag

Reference Note

1

Cheyne, J A, & Rubin, K H Playful precursors of problem-solving m preschoolers Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the

Society for Research m Child Development,

Boston, April 1981

References

Allen, V Chddren as teachers New York Academic Press, 1976

Asher, S R , Markell, R A , & Hymel, S Identifying children at nsk m peer relations- a cntique of the rate-of-mteraction approach to

assessment Child Vevdopmera, 1981, 52(4),

123&-1245

Asher, S R , Singleton, L C , Tuisley, B R , &

Hymel, S A reliable sociometnc measure for

preschool children Developmental Psychology, 1979, 15, 443-444

Behar, L , & Strmgfield, S A behavior rating scale

Kenneth H. Rubin

for the preschool child Development^ Psy-"

chology, 1974, 10, 601-^10

Combs, M L , & Slaby, D A Social skills traimng

with children In B Lahey & A Kazdm

(Eds ), Advances in chnictd chdd psychology

Vol 1. New York Plenum, 1978

Cowen, E L , Pederson, A , Babigian, H , Izzo,

L D , & Trost, M A Long-term follow-up of

early detected vulnerable children Journal of

Constdtmg and Clinical Psychology, 1973, 41,

438-446

DeVnes, R The development of role-taking as reflected by the behavior of bnght, average, and

retarded children m a social guessing game

ChUd Devdopmera, 1970, 4 1 , 759-770

Furman, W , Rahe, D F , & Hartup, W W Rehabihtation of socially withdrawn preschool children through mixed-age and same-age sociallzabon Child Development, 1979, 50, 915922

Garvey, G Play Gambndge, Mass Harvard University Press, 1977

Goldman, J A , Corsmi, D A , & deUnoste, R Imphcations of positive and negabve sociometnc

status for assessmg the social competence of

young children Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 1980, 1, 209-220

Gottman, J M Toward a definihon of social isolation in children Chdd Development, 1977,

48, 513-517

Hartup, W W Peer relabons and the growth of

social competence In M W Kent & J E Rolf

(Eds ), Primary prevention of psychopathology Vol 3. Social competence tn children

Hanover, N H University Press of New En^and, 1979

Jenmngs, K D People versus object orientation,

social behavior, and mtellectual abihties m

children Developmental Psychology, 1975, 11,

511-519

Parten, M B Social participation among preschool

657

children Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1932, 27, 243-269

Piaget, J The language and thought of the chdd

London Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1926

Piaget, J The moral judgment of the child Glencoe. III Free Press, 1932

Roff, M , Sells, S B , & Golden, M M Socud adjustment and personality development m chddren Minneapolis Umversity of Minnesota

Press, 1972

Rubm, K H , & Everett, B Social perspecbvetaking m young children In S Moore & C

Cooper (Eds ), The young chdd Vol 3

Washington, D G National Association for

the Education of Young Children Pubhcabons,

m press

Rubm, K H , Fem, G G , & Vandenberg, B Play

In E M Hethenngton (Ed ), Handbook of

chdd psychology Vol 3 Social develojnnent

New York Wiley, m press

Rubm, K H , Maiom, T L , & Homung, M Free

play behaviors m middle- and lower-class preschoolers Parten and Piaget revisited Chdd

Development, 1976, 47, 414-119

Rubm, K H , Watson, K , & Jambor, T Free-play

behaviors in preschool and kindergarten children Chdd Development, 1978, 49, 534-536

Smilansky, S The effects of sociodramatic play on

dtsadvantaged preschool chddren New York

Wiley, 1968

Smith, P K, & Dutton, S Play and traimng m

direct and innovative problem solving Chdd

Development, 1979, 50, 830-836

ack, G, & Shure, M B Social adjustment m

young chddren Jossey-Bass, 1974

Sylva, K Play and learmng In B Tizard & D Harvey (Ekls ), The btdogy of piay London

SIMP/Hememann, 1977

Ullman, G H Teachers, peers, and tests as predictors of adjustment Journal of Educational

Psychology, 1957, 48, 257-267