Low-Wage Import Competition, Inflationary Pressure,and Industry

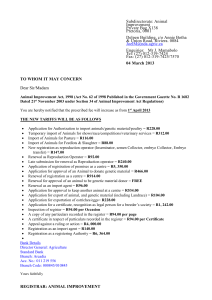

advertisement