ARTICLE IN PRESS

International Journal of Nursing Studies 45 (2008) 879–887

www.elsevier.com/locate/ijnurstu

Emotional labour, job satisfaction and organizational

commitment amongst clinical nurses: A questionnaire survey

Feng-Hua Yanga,, Chen-Chieh Changb

a

Department of International Trade, Aletheia University, 32, Chen-Li Street, Tamsui, Taipei 251, Taiwan

b

Institute of Management, Chung Yuan Christian University, Taiwan

Received 21 June 2006; received in revised form 24 January 2007; accepted 3 February 2007

Abstract

Background: According to Hochschild’s (1983. The Managed Heart. Berkeley: University of California Press)

classification of emotional labour, nursing staff express high emotional labour. This paper investigates how nursing

staff influence job satisfaction and organizational commitment when they perform emotional labour.

Objectives: This paper examines the relationship between emotional labour, job satisfaction, and organizational

commitment from the perspective of nursing staff.

Design: A questionnaire survey was carried out to explore these interrelationships.

Setting: Teaching hospital in Taiwan.

Participants: Questionnaires were distributed to 500 nursing staff; 295 valid questionnaires were collected and

analysed—a 59% response rate.

Methods: The questionnaires contained items on emotional labour, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment as

well as some basic socio-demographics. In addition, descriptive statistics, correlation and linear structure relation

(LISREL) were computed.

Results: Emotional display rule (EDR) was significantly and negatively related to job satisfaction. Surface acting (SA)

was not significantly related to job satisfaction but demonstrated a significantly negative relationship with

organizational commitment. Deep acting (DA) significantly and positively correlated with job satisfaction but

demonstrated no significance with organizational commitment. The variety of emotions required (VER) was not

significantly related to job satisfaction; frequency and duration of interaction (FDI) and negatively related to job

satisfaction; and job satisfaction significantly and positively correlated with organizational commitment.

Conclusions: We found that some dimensions of emotional labour significantly relate to job satisfaction. Job

satisfaction positively affects organizational commitment and has an intervening effect on DA and organizational

commitment.

r 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Emotional labour; Job satisfaction; Organizational commitment

What is already known about the topic?

Corresponding author. Tel.: +886 2 26212121x5306;

fax: +886 2 86318427.

E-mail address: leon@email.au.edu.tw (F.-H. Yang).

Nursing staff perform high emotional labour.

Employees’ expression of emotional labour influences

0020-7489/$ - see front matter r 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.02.001

job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

F.-H. Yang, C.-C. Chang / International Journal of Nursing Studies 45 (2008) 879–887

880

Correlation

coefficients denoting the relationship

between emotional labour and job satisfaction range

from 0.16 to 0.44.

What this paper adds

Some

dimensions of emotional labour significantly

relates to job satisfaction.

Job satisfaction has an intervening effect on deep

acting and organizational commitment.

The theoretical model proposed by this paper is

deemed a good fit.

1. Introduction

The first definition of emotional labour was proposed

by Hochschild (1983). Emotional labour requires that

one expresses or suppresses feelings that produce an

appropriate state of mind in others; that is, a sense of

being cared for in a convivial and safe place. When

emotions are transferred from personal behaviours to

commodities, organizations have begun to consider

using managerial measures to make employees utilize

emotional labour to maximize efficiency while working

(Morris and Feldman, 1996).

Emotional labour is considered by many to be an

important part of the role of many health care

professionals and it has been the focus of much debate

and empirical enquiry within a range of health care

settings, especially in nursing (Mann, 2005). According

to Hochschild’s (1983) classification of emotional

labour, nursing staff are required to express a higher

degree of emotional labour compared with other

professional and technical staff with similar jobs.

Numerous scholars have investigated the role of

emotional labour in nursing. According to Mann and

Cowburn (2005), nurses who perform emotional labour

are able to manage patient reactions by providing

reassurance and an outlet for emotions, thus directly

impacting their psychological and physical well-being

and recovery. Lynch (1989) argued that emotional

labour performed by nurses, to a certain extent,

generates and maintains ‘‘solidarity relationship.’’ That

is, emotional labour establishes an interpersonal relationship and is a symbolic expression of emotional

concern and caring that enables patients to feel at ease

and trust the nurses’ motives and actions (O’Brien,

1994). Smith and Kleinman (1989), in a study of medical

professionals, noted that their development toward

emotional neutrality is part of a hidden curriculum.

Under great pressure to prove that they are worthy of

entering the nursing profession, students are afraid to

admit that they are uncomfortable with patients or

procedures, typically hiding these feelings behind a

‘‘cloak of competence.’’

Cranny et al. (1992) defined job satisfaction as ‘‘an

affective (that is, emotional) reaction to one’s job,

resulting from an incumbent’s comparison of actual

outcomes with desired (expected, deserved, etc.)

outcomes’’. Locke (1969) argued that job satisfaction

is the ‘‘pleasurable emotional state resulting from

appraisal of one’s job as achieving or facilitating one’s

job values’’. Job dissatisfaction, meanwhile, is an

unpleasurable emotional state resulting from an appraisal of one’s job as frustrating or blocking the attainment

of one’s values. It is therefore clear from the above that

job satisfaction is an integral variable of organizational

theory.

Previous theoretical work on emotional labour

suggested a negative relationship between emotional

labour and job satisfaction. However, two empirical

tests of this relationship (Adelmann, 1989, Wharton,

1993) contradicted the above view. Moorman’s (1993)

study found that when only one dimension is used to

measure the relationship between emotional labour and

job satisfaction, the correlation coefficients range from

0.16 to 0.44, suggesting that measuring emotional

labour with only one dimension is inappropriate. Not

until Morris and Feldman (1996) used an emotional

interaction module to redefine emotional labour. Lin

(2000) studied emotional labour and found that it

should be measured using five dimensions—emotional

display rule (EDR), surface acting (SA), deep acting

(DA), variety of emotions required (VER), frequency

and duration of interactions (FDI). However, few

studies have investigated the relationship between these

dimensions and job satisfaction.

Ekman (1973) referred to the rules regarding appropriate emotional expression display rules. According to

Ekman, display rules are norms and standards of

behaviour indicating what emotions are appropriate in

a given situation and how these emotions should be

publicly expressed. In the topic of display rules,

Ashforth and Humphrey (1993) emphasized on the

expression aspect whereas Hochschild (1983) noted that

managing inner feelings is crucial. Hochschild (1983),

who pointed out that emotions cause alienation and

estrangements from one’s feelings, further hypothesized

that emotional display is negatively correlated with job

satisfaction.

In SA, employees modify and control their emotional

expressions (Morris and Feldman, 1997; Pugliesi, 1999;

Lin, 2000). For example, employees may fake a smile

when in a bad mood or interacting with a difficult

customer. Morris and Feldman (1997) identified conflicts between emotions genuinely felt and emotions to

be displayed in organizations as ‘‘emotional dissonance’’. In other words, the act of expressing sanctioned

emotions during interpersonal interactions becomes

more demanding when expression requires increased

effort to control true feelings. Rutter and Fielding (1988)

ARTICLE IN PRESS

F.-H. Yang, C.-C. Chang / International Journal of Nursing Studies 45 (2008) 879–887

found that a need to suppress inauthenticity felt

emotions was negatively correlated with job satisfaction.

Hochschild (1983) defined ‘‘deep acting’’ as individuals trying to influence what they feel in to ‘‘become’’

the role they are asked to play. In this case, expressive

behaviours and inner feelings are regulated (Zapf, 2002;

Lin, 2000). DA is when an employee must expend effort

to regulate emotions. During DA, there is a need to

actively strive to invoke thoughts, images, and memories

to induce a certain emotion (Ashforth and Humphrey,

1993). Broheridge and Grandey (2002) argued that DA

involves treating a customer as someone deserving

authentic expression, and the positive feedback from a

customer can increase personal efficacy. We propose

that DA is positively correlated with job satisfaction.

Morris and Feldman (1996) opined that emotional

work requires expression of a variety of emotions. The

requirement to display emotions can be either positive,

neutral—in the case of a judge who wants to display

dispassionate authority and independence—or negative,

e.g., a policeman who shows severity and anger when

communicating with drunken adolescents. There are

some jobs, such as kindergarten teachers, nurses, and

psychotherapists in which a variety of emotions are

required (Zapf, 2002; O’Brien, 1994). Frequent changes

in the emotions displayed over a limited period require

more planning and anticipation on the part of employees, and thus, they entail greater emotional labour and

more role load (Morris and Feldman, 1996; Lin, 2000).

Therefore, the need to express a variety of emotions

should be negatively correlated with job satisfaction.

Frequency of emotional displays has been the most

examined component of emotional labour (Morris and

Feldman, 1996; Zapf, 2002). In fact, more or less, all

studies that somehow measured emotion work measured

the frequency and it was the basic idea of Hochschild

(1983) that too frequent emotional displays would

overtax the employees and lead to alienation and

exhaustion (Zapf, 2002). Rafaeli (1989) and Sutton

and Rafaeli (1988) investigated convenience stores and

suggested that the duration of interaction is related to

the scriptedness of social interactions. This finding

implies that the level of effort required for emotional

display in a short period is minimal. Conversely,

emotional displays of long duration should require

more effort, and thus, increased emotional labour

(Morris and Feldman, 1996; Lin, 2000). Thus, FDI

should be negatively correlated with job satisfaction.

Udo et al. (1997) argued that how satisfied employees

feel about their jobs affects their loyalty towards their

organizations. Mowday et al. (1982) pointed out that job

satisfaction can be an antecedent variable for organizational commitment. A number of studies found that job

satisfaction positively correlates with organizational

commitment (Martin and Bennett, 1996; Schwepker,

2001).

881

Although there are several definitions of organizational commitment, a common theme in most is that

committed individuals believe in and accept organizational goals and values, and are willing to remain within

their organizations, and willing to provide considerable

effort on their behalf (Mowday et al., 1979). Hence,

organizational commitment acts as a ‘‘psychological

bond’’ to an organization that influences individuals act

in ways that are consistent with the organization’s

interests (Porter et al., 1974). High or low organizational

commitment is related to employee’s turnover intention

(Martin and Bennett, 1996; Schwepker, 2001; Wong and

Law, 2002) and productivity (Becker et al., 1996; Martin

and Bennett, 1996). Wong and Law (2002) stated that

employees’ performance of emotional labour changes

their organizational commitment. Grandey (2000) noted

that in studying emotional labour, a trend is to measure

SA and DA. Thus, this study explores how SA and DA

affect organizational commitment.

Hochschild (1983) argued that inauthentic SA over

time results in a feeling detachment from one’s true

feelings and from others’ feelings. Feeling-diminished

personal accomplishment is likely when an employee

believes that the displays were not efficacious or were

met with annoyance by customers (Ashforth and

Humphrey, 1993). The inauthenticity of this surface

acting process, showing discrepant from feelings, affects

employee behaviour (Pugliesi, 1999; Ashforth and

Humphrey, 1993). We propose that SA is negatively

correlated with organizational commitment.

Hochschild (1983) discussed two avenues for DA: (a)

exhorting feelings, whereby one actively attempts to

evoke an emotion; and, (b) trained imagination, whereby one actively invokes thoughts, images, and memories

to induce the associated emotion (thinking of a wedding

to feel happy). DA is directly focused on one’s inner

feelings (Ashforth and Humphrey, 1993; Mann, 2004);

given the increased psychic effort involved in DA,

this form of emotional labour is more consistent

with a strong concern for one’s customers. We propose

that DA is positively correlated with organizational

commitment.

Based on literature findings and empirical study, this

paper investigates the relationship between emotional

labour performed by nursing staff and job satisfaction

and organizational commitment.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and procedure

In total, 500 full-time nurses participated in this study.

Participants in this convenience sample returned 295

valid questionnaires—a 59% response rate. The sample

was 100% female, of which 28.5% were married. Most

(89.5%) were aged o35 years. Most had 43 years of

ARTICLE IN PRESS

882

F.-H. Yang, C.-C. Chang / International Journal of Nursing Studies 45 (2008) 879–887

work experience (60%) and 28.5% had X7 years of

experience.

Wallbott and Scherer (1989) indicated that the use of

a questionnaire to collect information about emotional

experience and expression can offer a number of

advantages, including assess to more emotional experiences over a longer period of time. All respondents

participated voluntarily in the study, and assurances of

anonymity were made and kept. Non-response bias was

checked by means of a time trend extrapolation test in

which characteristics of early respondents were compared with those of late respondents (Armstrong and

Overton, 1977). No significant differences were identified (F ¼ 0.65, po0.687), suggesting that non-response

bias is less likely.

2.2. Measures

This study utilized a pretest to enhance reliability and

validity. When the corrected item-total correlation was

o0.45, and deleting the item increased Cronbach’s a, the

item was deleted.

Emotional labour was measured with a slightly

modified scale developed by Lin (2000). The 24-item

measure contained five dimensions—EDR, SA, DA,

VER, and FDI. A 7-point Likert scale was used, with

anchors ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly

agree). EDR was the level to which employees reported

that their emotional displays were controlled by their

jobs. Items asked the extent to which the employee is

required by organization to show (or hide) emotion in

order to be effective on the job. SA refers to modifying

and faking expressions. DA is the extent to which an

employee modifies feelings to meet display rules. VER is

the need to display different emotions with different

patients. FDI is the average number of minutes and rate

required for a typical transaction. Four items were

deleted after the pretest. Internal consistency was

measured using Cronbach’s a with reliability coefficients

of 0.79 for EDR (five items), 0.85 for SA (three items),

0.85 for DA (six items), 0.86 for VER (four items) and

0.75 for FDI (two items).

Job satisfaction was adopted from the Minnesota

Satisfaction Questionnaire (Weiss et al., 1967). It was

measured using a 20-item scale containing two dimensions: internal satisfaction (IS) and external satisfaction

(ES). A 7-point Likert scale was adopted, with anchors

ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

No item was deleted during the pretest. Internal

consistency was measured using Cronbach’s awith

reliability coefficients of 0.92 for IS (twelve items) and

0.83 for ES (eight items).

Organization commitment was measured by the

Organization Commitment Questionnaire developed by

Mowday et al. (1982), which used 15 items containing

three dimensions: value commitment (VC), effort

commitment (EC) and, retention commitment (RC). A

7-point Likert scale was used, with anchors ranging

from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). This

questionnaire has six reverse items. One item was deleted

after the pretest. Internal consistency was measured

using Cronbach’s a; reliability coefficients were 0.81 for

VC (five items), 0.81 for EC (four items) and 0.87 for RC

(five items).

Socio-demographic variables, such as age, gender,

employment status, and marital status were examined.

Table 1 provides the reliability analysis results of

emotional labour, job satisfaction and organizational

commitment. Each scale had satisfactory reliability with

coefficient a above 0.70.

Furthermore, this study examined convergent

and discriminant validity using confirmatory factor

analysis on LISREL VII (Jöreskog and Sörbom,

1982). Evidence of convergent validity was found in

the parameter estimates and t-values. First, parameter estimates were high in value and t-values were

statistically significant (greater than 2.0), meeting

the criteria proposed by Anderson and Gerbing (1988)

for convergent validity. Second, the proportion of

variation in the indicators captured by the underlying constructs should be higher than the variance

due to measurement error (Fornell and Larcker,

1981). The values of the average variance extracted

were 0.56 for EDR, 0.65 for SA, 0.61 for DA, 0.78 for

VER, 0.74 for FDI, 0.50 for IS, 0.48 for ES, 0.67 for VC,

and 0.56 for EC, 0.62 for RC. Almost all exceeded a

suggested critical value of 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker,

1981).

Table 1

Reliabilities analysis

Dimensions

Cronbach a Dimensions

Cronbach a Dimensions

Emotional display rule

Surface acting

Deep acting

Variety of emotional required

Frequency and duration of interaction

.79

.85

.85

.86

.75

Internal satisfaction .92

External satisfaction .82

Value commitment

Effort commitment

Retention commitment

Emotional labour

.89

Job satisfaction

Organizational commitment .91

.93

Cronbach a

.81

.81

.87

ARTICLE IN PRESS

F.-H. Yang, C.-C. Chang / International Journal of Nursing Studies 45 (2008) 879–887

883

goodness-of-fit index (GFI) of 0.90, comparative fit

index (CFI) of 0.93, and root mean square residual

(RMSE) of 0.049, indicating acceptable fit.

Table 3 presents the LISREL estimates of structural

model coefficients. The path coefficients from emotional

display rule to job satisfaction were significant and

negative (g11 ¼ 0.24, t ¼ 2.93). SA was not significantly correlated with job satisfaction (g21 ¼ 0.10,

t ¼ 1.25), but significantly and negatively correlated

with

organizational

commitment

(g12 ¼ 0.23,

t ¼ 3.35). DA was significantly and positively correlated with job satisfaction (g31 ¼ 0.30, t ¼ 3.24), but not

with organizational commitment (g22 ¼ 0.10, t ¼ 1.30).

Thus, when SA, nurses modify and control their

emotional expressions. The inauthenticity of this surface-level process, showing expressions that differ from

their feelings, is not significantly related to job satisfaction but significantly related to organizational commitment. DA is the process in which internal thoughts and

feelings are altered to meet mandated display rules. DA

is significantly related to job satisfaction but not with

organizational commitment. VER was not significantly

correlated with job satisfaction (g41 ¼ 0.15, t ¼ 1.88).

FDI was significantly and negatively correlated with job

satisfaction (g51 ¼ 0.16, t ¼ 2.11). Job satisfaction

was significantly and positively correlated with organizational commitment (b11 ¼ 0.76, t ¼ 5.26).

Going a step further, we explored whether job

satisfaction has an intervening effect between SA, DA,

and organizational commitment. Table 4 presents the

results. Job satisfaction did not have a significant

intervening effect on SA (b ¼ 0.08, t ¼ 1.25). Thus, SA

cannot affect organizational commitment through job

satisfaction. However, job satisfaction demonstrated a

significant intervening effect on DA (b ¼ 0.23, t ¼ 3.20).

Thus, DA affects organizational commitment through

job satisfaction.

Discriminant validity can be established by demonstrating that the average variance extracted by a

particular construct from its indicators is greater

than its squared correlation (shared variance) with

another construct (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Each

of the squared phi coefficients between EDR and

every other variable in the study was examined.

Results indicated that each construct’s average variance extracted was greater than its shared variance

with EDR. The following are the shared variances

between EDR and SA (0.30), DA (0.01), VER (0.00),

FDI (0.35), IS (0.18), ES (0.14), VC (0.13), EC (0.18),

and RC (0.14). Results of these analyzes provided

evidence for convergent and discriminant validity of the

constructs.

3. Results

Table 2 provides the means, standard deviations and

correlations for variables in this study. EDR was

significantly correlated with all job satisfaction subscales

and the organizational commitment subscale. Surface

acting did not exhibit significant correlation with the job

satisfaction subscale but show partial significance with

the organizational commitment subscale. DA was

significantly correlated with all job satisfaction subscales; however, DA was not significantly correlated

with organizational commitment subscales. VER was

not significantly correlated with job satisfaction subscales. FDI demonstrated a partially significant correlation with job satisfaction subscales.

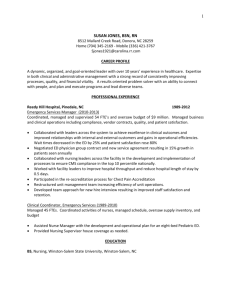

To test the model presented in Fig. 1, structural

equation modelling was implemented by LISREL 8

(Jöreskog and Sörbom, 1982). As recommended by

Anderson and Gerbing (1988), covariance matrices were

used as input for LISREL analyses. The fit indices for

the structural model included a w2/df ratio of 3.12,

Table 2

Means, standard deviations, correlation matrix

Variables

Mean

SD

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

l. EDR

2. SA

3. DA

4. VER

5. FDI

6. IS

7. ES

8. VC

9. EC

10. RC

5.46

5.60

6.41

3.91

5.56

5.18

4.59

4.52

4.90

4.49

1.38

1.05

0.57

1.42

1.03

0.93

1.04

0.92

0.95

1.11

1.00

0.47**

0.33**

0.01

0.29**

0.32**

0.35**

0.36**

0.31**

0.33**

1.00

0.26**

0.30**

0.36**

0.05

0.12

0.40**

0.02

0.38**

1.00

0.52**

0.30**

0.63**

0.47**

0.06

0.07

0.07

1.00

0.34**

0.08

0.10

0.17**

0.34**

0.19**

1.00

0.29**

0.01

0.04

0.09

0.11

1.00

0.83**

0.66**

0.56**

0.57**

1.00

0.58**

0.54**

0.53**

1.00

0.65**

0.76**

1.00

0.56**

1.00

Note: EDR, Emotional display rule; SA, surface acting; DA, deep acting, VER, variety of emotional required; FDI, frequency and

duration of interaction; IS, internal satisfaction; ES, external satisfaction, VC, value commitment; EC, effort commitement; RC,

retention commitment.*po0.05 **po0.01.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

F.-H. Yang, C.-C. Chang / International Journal of Nursing Studies 45 (2008) 879–887

884

-0.23

SA (X2)

0.10

EDR(X1)

-0.24

0.15

VER(X4)

-0.16

FDI(X5)

0.30

DA(X3)

0.76

Job satisfaction

0.49

IS(Y1)

0.83

ES(Y2)

Organizational

commitment

0.81

0.80

VC(Y3)

EC(Y4)

0.54

RC(Y5)

0.10

Fig. 1. Structural model coefficients. Note: w2 (df ¼ 26) ¼ 96.83 (P ¼ 0.000), 2. GFI ¼ 0.90, CFI ¼ 0.93, 3. RMSR ¼ 0.049.

Table 3

Path coefficient

Independent variable

Dependent variable

Job satisfaction

Emotional display rules

Surface acting

Deep acting

Variety of emotional required

Frequency and duration interaction

Job satisfaction

0.24** (2.93)

0.10 (1.25)

0.3** (3.24)

0.15 (1.85)

0.16* (2.11)

Organizational commitment

0.23** (3.35)

0.1 (0.30)

0.76** (5.26)

Note: ( ) is t value, *po0.05, **po0.01.

Table 4

Intervening effect with job satisfaction

Independent variable

Dependent variable

Organizational commitment

Surface acting

Deep acting

0.08 (1.25)

0.23** (3.20)

Note: ( ) is t value, *po0.05, **po0.01.

4. Discussion

Many scholars studying the relationship between

emotional labour and job satisfaction found different

results given in different subjects and industries. For

example, in an exploratory research on flight attendants,

Hochschild (1983) contended that having to perform

emotional labour causes eventual alienation or estrangement from one’s genuine feelings, and it thereby has

detrimental consequences for various aspects of psychological well-being.

Morris and Feldman (1997) provided direct empirical

evidence that previous research has overemphasized the

negative aspects of emotional labour. Sampling employees from multiple job categories in debt collection

agencies, military recruiting battalion headquartered

and nursing, Morris and Feldman found that emotional

dissonance is associated with higher emotional exhaustion and lower job satisfaction.

Wharton’s (1993) examination of the emotional labour

offered results that often directly contradict earlier studies.

Sampling employees from multiple job categories in a large

bank and a teaching hospital, Wharton discovered that

emotional labour is positively related to job satisfaction, a

finding inconsistent with Hochschild’ s (1983).

Ashforth and Humphrey (1993) suggested that emotional labour actually might make interactions more

predictable and help workers avoid embarrassing interpersonal problems. This should, in turn, help reduce

stress and enhance satisfaction.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

F.-H. Yang, C.-C. Chang / International Journal of Nursing Studies 45 (2008) 879–887

Smith and Kleinman (1989) believed that when

medical personnel can maintain a neutral mood,

he/she can maintain a proper distance to stay away

from psychological unhappiness. However, empirical

findings of an integrated approach adopted by this study

revealed that the relationship between emotional labour

and job satisfaction is uncertain.

Emotional labour has been explored in detail elsewhere and explained as involving the regulation and

management of feeling (Hochschild 1983, Smith 1992).

Theodosius’s (2006) concern was that emotional labour

in nursing was considered to be marginalized due to

organizational constraints and the low status attached to

emotion work within and outside of nursing (James,

1992; Smith, 1992).

For Freud, the original emotion only appears

unconscious because of its conscious ideational presentation resulting in its repression, but for Hochschild,

the original emotion is conscious. For example, a nurse

actually feels disgust towards the patient but represses

the feeling. In doing so, the idea that the nurse does not

feel disgust is interpreted by her conscious mind as

caring and kindness, and the emotion is identified as

sympathy. The feeling of disgust is never actually

unconscious, but the ideational presentation of the

nurse as caring has repressed it (Theodosius, 2006).

Thus, conscious and unconscious emotion which

directly impact on both internal and external behavior

patterns can bypass cognitive process (Theodosius,

2006).

Hochschild (1983) noted that when services are

provided during work, SA may produce mistakes and

dissatisfaction, and DA may produce satisfaction.

Hochschild was the first scholar to address SA and

DA, and she also examined the impact of SA and SA on

job satisfaction. However, she only described the

relationship between the two variables but did not offer

an empirical study to complement it. One of the main

objectives of this paper, therefore, is to provide an

empirical study for this proposition. Analytical results

indicated that SA does not have an obvious effect on job

satisfaction, and DA positively affects job satisfaction.

Of the five dimensions of job satisfaction, DA has the

most positive influence. Empirical results indicated that

nurses’ performance of DA does not diminish their level

of job satisfaction. Also, when nurses’ inner thoughts

and feelings match display rules, their level of job

satisfaction rises.

This article found no significant relationship between

VER and job satisfaction. According to Smith and

Kleinman (1989), medical staff can maintain an appropriate distance by preserving a natural mood. In the

relevant analysis, VER scored the lowest, indicating that

nurses do not have to tailor their emotions to different

patients, locations, customers, and levels of staff. The

significantly negative relationship between interaction

885

levels and job satisfaction may be caused by nurses

having to work long hours, and thus their interaction

levels have to be more frequent and lengthier.

Mowday et al. (1982) pointed out that job satisfaction

can be an antecedent variable for organizational

commitment. This study found that a positive relationship exists between job satisfaction and organizational

commitment. Furthermore, SA has a negative influence

on organizational commitment, indicating that when

nurses perform emotional labour that differs from their

inner feelings, it will not affect their degree of job

satisfaction but depress their organizational commitment. DA does not significantly influence organizational

commitment. This finding shows that when emotional

labour coincides with inner feelings, job satisfaction is

enhanced but the effect on organizational commitment

is negligible. Table 4 reveals that job satisfaction is a

good mediator of DA. Hospitals can therefore effectively utilize job satisfaction to enhance nursing staff’s

organizational commitment.

5. Limitations and future research directions

The five-component conceptualization of emotional

labour, empirical findings on the effect of emotional

labour, and the focus on positive and negative consequences of emotional labour all add to our improving

understanding of emotional labour. However, this study

has several limitations.

The current study is cross-sectional, so the direction

of causality cannot be tested. Future research of

emotional labour can benefit from longitudinal research

designs.

The questionnaire assessment of emotional experiences is susceptible to a number of artefacts, such as

social desirability and response distortion due to egodefence tendencies (Wallbott and Scherer, 1989). Additionally, questionnaire studies also suffer from common method variance problems (Podsakfoff et al.,

2003). Future research can avoid this potential source

of confounding by collecting data from additional

sources.

Another possible limitation of this study was its focus

on a teaching hospital; the findings cannot therefore be

generalized to all hospitals. Future research can be

conducted on various hospitals to overcome this

problem.

If researchers intend to study whether emotional

labour negatively or positively affects organizations, we

suggest that they consider different job industries to

determine whether different job categories generate

different results (Broheridge and Grandey, 2002).

Lin and Chen (2001) found that emotional labour has

different impacts due to different personal characteristics and experiences. For example, those with high

ARTICLE IN PRESS

886

F.-H. Yang, C.-C. Chang / International Journal of Nursing Studies 45 (2008) 879–887

self-monitoring are outgoing, have a strong inclination to cooperate, and have strong interpersonal

skills. Also, those with strong awareness of self-image

will be the most competent in performing emotional

labour and will have a shorter learning time. Thus, in the

future, studies can focus on whether employees’ emotional labour is influenced by different personal characteristics.

References

Adelmann, P.K., 1989. Emotional labour and employee wellbeing. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of

Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Anderson, J.C., Gerbing, D.W., 1988. Structural equation

modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step

approach. Psychology Bulletin 103 (3), 411–423.

Armstrong, J.S., Overton, T.S., 1977. Estimating nonresponse

bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research 14,

396–402.

Ashforth, B.E., Humphrey, R.H., 1993. Emotional labour in

service roles: the influence of identity. Academy of Management Review 18 (1), 88–115.

Becker, T.E., Robert, S.B., Daniel, M.E., Nicole, L.G., 1996.

Foci and bases of employee commitment: implications for

job performance. Academy of Management Journal 39 (2),

464–482.

Broheridge, C.M., Grandey, A.A., 2002. Emotional labour and

burnout: compairing two perspectives of ‘‘people-work’’.

Journal of Vocational Behavior 60, 17–39.

Cranny, C.J., Smith, P.C., Stone, E.F., 1992. Job Satisfaction:

How People Feel About their Jobs and How it Affects their

Performance. Lexington Press, New York.

Ekman, P., 1973. Cross-cultural Studies of Facial Expression: a

Century of Research in Review. Academic Press, New

York, pp. 169–222.

Fornell, C., Larcker, D.F., 1981. Evaluating structural equation

models with unobservable variables and measurement error.

Journal of Marketing Research 18, 39–50.

Grandey, A., 2000. Emotion regulation in the workplace: a new

way to conceptualize emotional labour. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 5 (1), 95–110.

Hochschild, A.R., 1983. The Managed Heart. University of

California Press, Berkeley.

James, N., 1992. Emotional laobur: skill and work in the social

regulation of feeling. Sociology of Health and Illness 14 (4),

488–509.

Jöreskog, K.G., Sörbom, D., 1982. Recent developments in

structural equation modeling. Journal of Marketing Research 19, 404–416.

Lin, S.P., 2000. A study of the development of emotional

labour loading scale. Sun Yat-Sen Management Review 8

(3), 427–447.

Lin, S.P., Chen, Y.A., 2001. The study of display rules and

socialization process of the emotional labours. Commerce

and Management Quarterly 2 (3), 319–343.

Locke, E.A., 1969. What is job satisfaction? Organizational

Behavior and Human Performance 4, 309–336.

Lynch, K., 1989. Soldiary Labour: its nature and marginalization. The Sociological Review 37, 1.

Mann, S., 2004. ‘People-work’: emotion management, stress

and coping. British Journal of Guidance and Counseling 32

(2), 205–221.

Mann, S., 2005. A health care model of emotional labour; an

evaluation of the literature and development of a model.

Journal of Health, Organization and Management, Special

Issue on Emotion 19 (4), 317–323.

Mann, S., Cowburn, J., 2005. Emotional labour and stress

within mental health nursing. Journal of Psychiatric and

Mental Health Nursing 12, 154–162.

Martin, C.L., Bennett, N., 1996. The role of justice judgments

in explaining the relationship between job satisfaction and

organization commitment. Group and Organization Management 21 (1), 84–104.

Moorman, 1993. The influence of cognitive and affective based

job satisfaction measures on the relationship between

satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior. Human Relations 46 (6), 759–776.

Morris, A.J., Feldman, D.C., 1996. The dimensions antecedents

and consequences of emotional labour. Academy of

Management Review 21, 986–1010.

Morris, A.J., Feldman, D.C., 1997. Managing emotions

in the workplace, Journal of Managerial Issues 9 (3),

257–274.

Mowday, R., Porter, W.L., Steers, M.R., 1979. The measure of

organizational commitment. Journal Vocational Behavior

14, 224–247.

Mowday, R., Porter, W.L., Steers, M.R., 1982. Employeeorganization linkage-the psychology of commitment absenteeism and turnover. Academic Press, New York.

O’Brien, M., 1994. The managed heart revisited: health and

social control. The Sociological Review, 393–413.

Podsakfoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y., Podsakoff, N.P.,

2003. Common method diases in behavioral research: a

cirtical review of the literature and recommended remedies.

Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (5), 879–903.

Porter, W.L., Mowday, R., Steers, M.R., Boulian, P.V., 1974.

Orgainzational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover

among psychiatric technicians. Journal of Apply Psychological 59, 603–609.

Pugliesi, K., 1999. The consequences of emotional labour:

effects of work stress, job satisfaction, and well-being.

Motivation and Emotion 23 (2), 283–316.

Rafaeli, A., 1989. When clerks meet customer: a test of

variables related to emotional expression on the job. Journal

of Applied Psychology 74, 385–393.

Rutter, D.R., Fielding, P.J., 1988. Sources of occupational

stress: an examination of British prison officers. Work and

Stress 2, 291–299.

Schwepker Jr, C.H., 2001. Ethical climate’s relationship to job

satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover

intention in the salesforce. Journal of Business Research

54, 39–52.

Smith, A.C., Kleinman, S., 1989. Managing emotions in

medical school: students’ contacts with the living and the

dead. Social Psychology Quarterly 52 (1), 56–69.

Smith, P., 1992. Emotional Labour of Nursing. Macmillan,

Houndsmill.

Sutton, R.I., Rafaeli, A., 1988. Untangling the relationship

between displayed emotions and organizational sales.

Academy of Management Journal 31, 461–487.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

F.-H. Yang, C.-C. Chang / International Journal of Nursing Studies 45 (2008) 879–887

Theodosius, C., 2006. Recovering emotion form emotion

management. Sociology 40 (5), 893–910.

Udo, G.J., Guimaraes, T., Igbaria, M., 1997. An investigation

of antecedents of turnover intention for manufacturing

plant managers. International Journal of Operations and

Production Management 17 (9), 912–924.

Wallbott, H.G., Scherer, K.R., 1989. Assessing emotion by

questionnaire. In: Plutchik, R., Kellerman, H. (Eds.), Emotion: Theory, Research, and Experience. The Measurement of

Emotion, Vol. 4. Academic Press, New York, pp. 55–82.

Weiss, D.J., Davis, R.V., England, G.W., Lofguist, L.H., 1967.

Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire.

887

Industrial Relation Center, University Minnesota, Minneaplois, NM.

Wharton, A., 1993. The affective consequences of service work:

managing emotions on the job. Work and Occupations 20

(2), 205–232.

Wong, C.S., Law, K.S., 2002. The effects of leader and follower

emotional intelligence on performance and attitude:

an exploratory study. The Leadership Quarterly 13,

243–274.

Zapf, D., 2002. Emotion work and psychological well-being: a

review of the literature and some conceptual considerations.

Human Resource Management Review 12, 237–268.