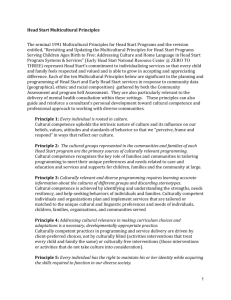

Curricula Enhancement Module Series

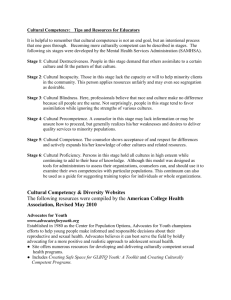

advertisement