Sustaining Software-Intensive Systems

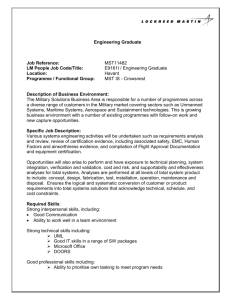

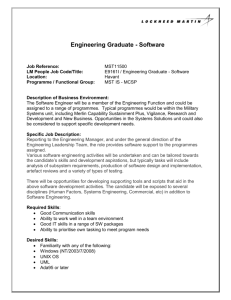

advertisement