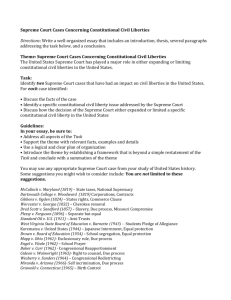

Students and the Supreme Court: A Lexicon of Laws

advertisement