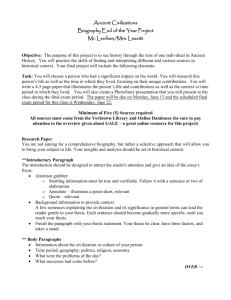

Suggested Style for Survey of Forest Ecology Laboratory Reports

advertisement

FOR 3364

Survey of Forest Ecology and Management

S. M. Zedaker

Suggested Style for

Survey of Forest Ecology Laboratory Reports

1. Introduction

Research, a studious critical inquiry and examination aimed at the discovery and interpretation of

new knowledge, is a vital part of every professional's job. Research is not just something done by

scientists working at universities or independent laboratories, but is an activity in which every

professional resource manager is involved and which sets professionals apart from technicians. The

code of ethics of nearly every profession dictates that practitioners use only the most up-to-date

information and technology to perform their tasks; to do this requires research! Whether the critical

inquiry and interpretation is done to purchase a new timber tract, retool a pulp mill, or develop a new

management strategy for spotted owl, it is still research. Inevitably, research involves designing a

study, collecting and analyzing data, and presenting the results, often in the form of a written report.

The process of writing, evaluating, and rewriting research findings makes the author think more

deeply about the work. Accurate, clear, and concise writing is essential to effective communication

among professionals. The research reports you will prepare will provide writing experience different

from that associated with a library term paper. A research report is based on one's own data and

involvement in an organized investigation.

2. General Format and Style

A widely accepted format for research reports is one that begins with a title and a by-line identifying

what the work is about and who did it, followed by sections such as Introduction, Methods and

Materials, Results, Discussion, Summary and/or Conclusions, and Literature Cited. Often, an

abstract at the beginning of the paper will appear in place of a summary at the end. This format

serves as a framework for a more detailed outline which must be prepared before the paper is

constructed.

The style of a research report varies depending on the intended audience. Most professional writers

and editors find that the style of research reports is poor, largely because the authors lack experience

and/or training in technical writing. A good reference for a "beginning" biological writer is the CBE

Style Manual (Council of Biological Editors 1978). There are numerous texts on technical writing

that would also be helpful. The following general guidelines, gleaned from many of these sources,

will help your writing (and paper grades) if used.

a. Considerable debate still rages about the use of the first person ("I" or "we") in technical writing.

For now, do not use the first person. By the same token, do not use indirect statements like "this

author" or "these researchers." For example, when describing how tree diameters were taken, you

might write: "The diameters, at 4.5 ft above ground, of ten trees on each plot were measured to

the nearest 0.1 inch using a caliper."

b. All manuscripts should be typed double-spaced, with one-inch margins all around. Do not

hyphenate words or right-justify; an uneven margin is of little concern.

c. Do not use footnotes, and avoid the use of direct quotations. Direct quotations are reserved for

rare instances in technical writing when it is impossible to improve on the original wording, or

when the wording itself is the object of comment. Use the style for citations given in section 6

below.

1

d. Make liberal use of headings and subheadings for major sections of the reports. These are

generally the product of a good working outline, and they help organize the reader's thinking.

e. Always use the past tense for the Methods and Materials section. You have already completed

the work by the time the paper was written.

f. Avoid the use of long or complex sentences with excessive use of commas and conjunctions

("and," "but," "or"). These sentences often obscure your meaning and reduce readability.

g. Do not use noninformative abbreviations like "etc." and phrases such as "and so on" or "and the

like."

h. The first time a species is mentioned, give its common and Latin name and the author. Common

names suffice for subsequent citations.

i. Be affirmative in your writing. Do not hide behind noncommittal statements. For example, using

"the data could possibly suggest" implies that the data may actually show nothing; use "the data

show" instead.

j. Avoid the use of contractions (don't, can't) and possessives (fire's effect, slope's impact). By

convention, possessives are only used in conjunction with living organisms.

k. The rules for numbers are varied and complex, but need not be. In general, use Arabic numerals

for all numbers in a sentence if the numbers are 10 or above or include decimal points. However,

never start a sentence with an Arabic numeral. Round off numbers to their justifiably significant

digits. After all, how much is 0.0001 of a board foot, or how can you have 0.05 of an animal per

acre?

l. Avoid repeating findings and thoughts. Decide where a statement about your work fits best and

do not repeat it elsewhere.

m. Be concise. Include all that is necessary, but do not pad the report with extraneous information.

3. Title

Titles should be concise and descriptive of contents and scope. They should avoid gobbledygook

like "some aspects of" or "in relation to." Avoid articles, adjectives and adverbs. Titles should not be

excessively long, but should be specific and clear.

4. Abstract

An abstract is a concise statement of the problem, your general methods, basic findings and

conclusions. Poor abstracts tend to read more like expanded tables of content. A poor abstract might

read:

"The food habits of various song birds in a city were studied. The data were analyzed

statistically and certain similarities and differences between the species were found.

Conclusions about feeding habits, habitats, and niche segregation were reached."

A good abstract on the same subject would read:

"The stomach contents of blue jays, cardinals, and English sparrows, were identified from a

random sample of 50 birds captured in downtown Blacksburg, Virginia. Analysis of the

amount of overlap of food types showed that blue jays and English sparrows consumed

similar foods. As an example of niche segregation in an urban environment, blue jays and

sparrows occupy similar habitats while cardinals occupy dissimilar habitats."

2

5. Introduction Section

The introduction is critical to maintaining a reader's interest in the report. It should show why the

problem is important. It should define the scope of the work to be reported or the objective of the

exercise. It may incorporate a brief literature review. However, the introduction should be brief;

maybe only a few sentences are necessary to introduce the reader to the subject. This part of the

paper presents the background and justification for your study.

6. Literature Review Section

The literature review should be something more than a collection of loosely connected citations. The

writer must strive to synthesize the bits of literature into a meaningful whole. This section should

review what others have said about the topic of your paper. After reading your Literature Review, a

critical reviewer should be convinced that the topic has been comprehensively covered.

Only literature actually read should be cited. If, while reading an article by Smith (1960), you find an

interesting article attributed to Tribbett (1900) in an obscure publication you cannot hope to find,

you might state: "According to Smith (1960), Tribbett reported in 1900 that. . ."

It is preferred that literature be cited with dates, as: "Brown and Pauly (1940) found. . . or. . . and no

trees were damaged (Jones, 1960)"

If more than two authors cooperated on an article, it may be cited as: "Singleton et al. (1939)

reported. . ."

Common knowledge (for example, "Trees are green" or "Pines have needles") need not be attributed

to any citation. However, if specific information (especially that including quantitative data) is used

(for example, "Trees have green foliage that reflects light at wavelengths between 0.5 and 0.6 m"), it

should be followed by an appropriate citation (Monteith 1973).

Be sure to include only those findings that relate specifically to your topic. Establish the connection

between your citations and your own work.

7. Materials and Methods Section

This should simply be an account of what, where, when, and how. It should always be written in the

past tense. A concise and clear explanation of the experimental procedures should be given in

sufficient detail to permit another to duplicate the study if desired. In a field study, a general

description of the field site is needed. Specific equipment should be mentioned only if it may make a

difference in the results. The units and resolution of any quantitative data should always be included.

Be sure to include the methods used to compile or analyze the data.

8. Results Section

This portion of the report gives the facts found, even if they are contrary to hypothesis or

expectation. Your results should be presented succinctly with an appropriate explanation. All of the

basic data should not be presented here. These data should go in the Appendix. The results are often

presented in a table, graph, or an equation (see Section 12). However, the Results Section is not just

a collection of facts and figures; it should contain an explanation and description of the data. Tell the

reader what patterns, trends, or relationships were found in the data. For example, do not say, "The

species-area curve is presented in Figure 1." Tell the reader what Figure 1 actually shows, as in,

"Figure 1 shows that the number of species per unit area increases with increasing site quality."

Label figures and tables properly (see section 12) and cite all of them in your text. Too often, figures

and tables are included in reports without their purpose being explained to the reader.

3

9. Discussion Section

This should be the most constructive part of your paper. In the previous section the results were

summarized and described. In the Discussion Section, the results should be interpreted, critically

evaluated, and compared to other research findings. Examine the amount and possible sources of

variation and bias in your data. Determine the impact of this variation on the interpretations that can

be made. Develop arguments for and against your hypotheses and interpretations. Often, the Results

and Discussion are combined into a single section.

10. Summary and/or Conclusion Section

In most reports this may be rather brief. However, you should be able to discuss the significance of

your results. The conclusions must be supported by your results and discussion. Do not make

generalizations that are not based on your data, known facts, or reason.

11. Literature Cited

Literature is listed in alphabetical order. Examples of proper form:

Kozlowski, T. T., and R. C. Ward. 1961. Shoot elongation characteristic of forest trees. For. Sci.

7:357-368.

Note: If pages are numbered consecutively throughout the year in the publication, the issue number

need not be given.

Snedecor, G. W. 1956. Statistical Methods. 5th ed. Iowa State College Press, Ames. 534 pp.

Zak, B., and R. G. McAlpine. 1957. Rooting of shortleaf and slash pine needle bundles. USDA

For. Serv. Sta. Note SE-119. Note 112. 2 pp.

12. Guidelines for Tables and Figures

Examples of good tables and figures can be found in most scientific journals. A few examples are on

the next page of this handout.

There are specific ways to format tables and figures. Different publications may have variations in

style, but some general guidelines apply to almost any situation. Some of these rules are common to

tables and figures, while other rules apply to either tables or figures, but not both.

Difference between a Figure and a Table

Figures are graphic representations of information: photographs, maps, drawings, histograms,

graphs, or charts (examples 1-3 below). Tables are basically lists of information in various categories

(example 4)

4

5

Table and Figure Format

a. Tables and figures must have complete titles that allow them to stand alone and be

understood. Ask yourself, "If I saw only this table (or figure) and its title, would it make

sense to me?" Don’t rely on the paper to interpret the table or figure.

b. You may copy a table or figure from another source, but you must then cite the source in the

table or figure title (example 3). As with any other citation, a complete reference must appear

in the Literature Cited section of your paper.

c. Make a reference to each table and figure somewhere in the body of the paper. Don’t include

a table or figure without commenting on it and providing some interpretation of what it

shows. However, there is no need to waste a full sentence on this; instead, use a parenthetical

comment at the end of a sentence that interprets the data. An example of proper reference:

"The mean Virginia pine site index (50 years) of trees measured was 59 feet (Fig. 3)."

d. Tables and figures may be incorporated into the text as soon as possible after they are first

mentioned, or they may be grouped at the end of the text and before the Literature Cited

section.

e. The titles of tables appear at the TOP (example 4). The titles of figures appear at the

BOTTOM (examples 1-3).

f. Graphs must have labels and units on both axes (examples 1-3).

Guidelines for Creating Graphs

The spreadsheet and graphing programs available on microcomputers are easy to use with a little

practice, and they provide very professional results. Learn to use the software!

Independent vs. Dependent Variables

When comparing two variables using a graph, one variable will go along the x-axis (horizontal) and

the other variable will go along the y-axis (vertical). The placement of the variables on these axes

must be deliberate.

The independent variable is recorded as part of the data set. However, independent variables do not

depend on, and are not a function of, any other variable being graphed. In a cause-and-effect

relationship, the independent variable is the "cause." The set of possible values for the independent

variable can often be stated at the start of the experiment or data collection. For example, values for

FSQI will always be {3, 4, …, 15, 16}.

The dependent variable always goes on the y-axis. The dependent variable is usually the measured

variable of interest; it depends on, or responds to, the independent variable(s). Dependent variables

are a function of the independent variable and are thus the "effect" in a cause-and-effect relationship.

To complicate the issue, some variables can be either independent or dependent, depending on the

study and analysis. For example, tree height is the dependent variable if it is graphed as a function of

soil depth where soil depth is the independent variable. On the other hand, tree height is the

independent variable when the dependent variable is the number of bird nests per tree. Therefore,

you must always consider the relationship between variables. Ask yourself, "Which variable depends

on which?"

6

Examples of Dependent and Independent Variables

Dependent: depends on:

tree height

bird nests per tree

cation exchange capacity

soil porosity

Independent

soil depth

tree height

soil pH

soil particle size

13. Other Important Considerations

a. Cite, evaluate, and interpret all the data you have deemed important enough to be included in the

report. Failure to do this is the most common problem of inexperienced technical writers.

b. Do not ignore results just because they differ from textbook generalizations. Your data may not

be incorrect, just different; but why?

c. Do not select or screen data to make desired results apparent. Any "fudging" of data is dishonest

and unacceptable.

d. Do not discard data because of excessive variability or bias. There are some errors in nearly all

scientific data that, if recognized and accounted for, do not discredit the results.

e. Conversely, be careful about making small differences seem overly important. Different values

are not necessarily statistically or practically significantly different.

f. Get your mind working over different ways to present the information you have collected. Ten

draft figures may be needed to find the best one to be included in the paper.

g. Do not pad your paper with meaningless figures and calculations. Have good reasons for

including what you do, and draw conclusions from everything included.

h. Document ideas, conclusions, and hypotheses with data, literature citations, and sound reasoning.

Do not leave your ideas up in the air without support; that is the first thing instructors and

detractors will find to critique.

i. Relate your results to accepted principles and concepts. Explain any discrepancies. This will

show that you really do understand the problem you are studying.

j. Use a dictionary, computer spelling checker, and/or extreme care. Misspelled words or typing

errors indicate ignorance, carelessness, or both. Ignorance and carelessness are not good

attributes for professionals.

Much of the material for these suggestions was adapted from similar works by other authors. Most

notable among them are:

Duffield, J. W. 1965. Writing for a scientific and technical journal. J. of For. 63:10.

Bower, J. E., and J. H. Zar. 1984. Field and Laboratory Methods for General Ecology (2nd ed.)

W.C.B. Pub. Dubuque, IA. 226 pp.

7