Blood Politics, Racial Classification, and Cherokee

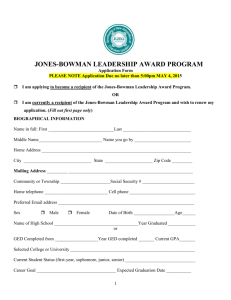

advertisement