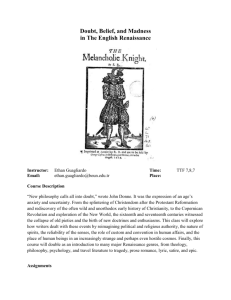

THE GREAT RECKONING: Who Killed Christopher

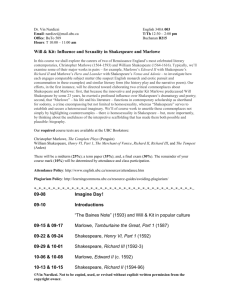

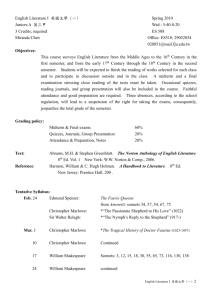

advertisement