I. British Colonial Policy after George Grenville

advertisement

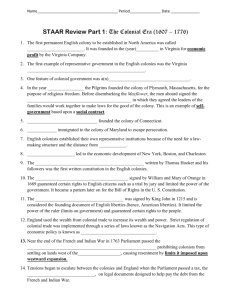

I. British Colonial Policy after George Grenville In the face of increasing controversy surrounding the Stamp Act, Grenville offered his resignation in 1765 and was replaced as Prime Minister by another Whig, Lord Rockingham. With the reluctant approval of the King, Rockingham recommended that the Stamp Act be repealed, and in March 1766 Parliament complied. While the announcement was met with delight in the colonies, they overlooked the simultaneous announcement of the Declaratory Act, passed by Parliament in order to impress upon the colonists that there had been no yielding of principle. The Declaratory Act asserted that the British legislature had the right to pass laws to regulate the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” In the summer of 1766, Rockingham‟s ministry fell, and he was replaced by William Pitt (the elder). The member of his cabinet who remains best remembered in America was Charles Townshend, Chancellor of the Exchequer, an ardent mercantilist and a firm believer in Parliamentary supremacy. Townshend was charged with finding new sources of revenue, the task which had brought Grenville such problems. Townshend proposed that the colonial distinction between internal and external taxes be accepted, and that full advantage be taken of the right which the colonists freely admitted to exist. Following Townshend‟s recommendations, Parliament in 1767 levied a series of duties on important colonial imports from England: lead, paper, paint, glass, and tea. To collect the duties, special revenue officers were sent to the colonies and the use of writs of assistance was legalized. II. The Colonial Protest Like Grenville, Townshend apparently thought he had done well, and he was amazed at the colonial response to the new duties. The American Revolution, in fact, may be said to have begun with the arrival of the new revenue officers and the military and naval units which were to assist them, for the colonists manifested an immediate disposition to resist the laws, and acts of violence became commonplace. Customs officers were attacked. Smugglers received widespread assistance and encouragement. Nonimportation associations were again formed, and patriotic women organized their consumers‟ boycotts and abstinence campaigns. In this campaign of resistance the colonial legislatures learned valuable lessons in intercolonial cooperation. At the insistence of Sam Adams, the Massachusetts General Court dispatched a “Circular Letter” to the other colonial legislatures, inviting united resistance to the policies of England. The Circular Letter and other tracts of the late 1760s carried the colonial argument against taxation one step beyond the point reached in the protests against the Stamp Act. Now it was argued that there were two types of external taxes, those designed to raise revenue and those designed to regulate trade, and that only the latter type could legally be imposed by Parliament. The most spectacular of the episodes of violence in the colonial reaction against the Townshend duties was the Boston “Massacre” of March 5, 1770. III. The Tories Take Over Despite the blame which many historians lay at the feet of the Tory party for „triggering‟ the Revolution, or at least, for allowing it to take place, in fact the Tories did not finally achieve a majority in Parliament and form a government until 1770. In 1770, Lord North, the leader of a group of Tories known as “the King‟s friends,” became Prime Minister, a position he would hold until 1782. To blame him for the revolution, which started during his ministry, however, is to overlook the fact that the revolutionary crisis was already far advanced, and that the policies which he undertook to apply were in no great degree different from those of his Whig predecessors. Indeed, his first move was quite conciliatory. Persuaded by English mercantilists that it was unwise to tax English goods, he secured the repeal of all the Townshend duties, save one: the tax on tea. From 1770-1773, there was an interlude of peace. Except for sporadic disturbances (such as the burning of the revenue cutter Gaspee in 1772), the first years of Lord North‟s administration were marked by relative quietude in the colonies. Taxed tea began to find its way into American stores and patriot homes. To radicals like Sam Adams, it seemed that the whole revolutionary movement might collapse. However, just as things seemed to be settling down, Parliament unwittingly poured fuel on the colonists‟ smoldering fire. In 1773, on the verge of bankruptcy, the East India Tea Company appealed to Parliament for aid. Because many M.P.‟s, particularly on the Whig benches, were stockholders in the company, relief was soon forthcoming. In addition to a loan and certain trading privileges, the company was given the right to transship tea from England to America without paying the customary duty of 12 pence per pound; the colonial duty of three pence per pound would, however, still have to be paid. The company was further authorized to place its own agents in the colonies, bypassing American importers and tea merchants. It was hoped that these concessions would enable the company to dispose of a 17 million pound surplus of tea without depressing the price in the world tea market. The Tea Act was remarkably effective in driving American conservatives into the ranks of the Sons of Liberty. Merchants became frantic with fear that the law would give the British a complete monopoly on the colonial tea market; not only the legitimate traders but also the smugglers of Dutch tea expected to be undersold by the East India Company. Businessmen viewed the act as a possible precedent for other monopolies, and in their determination to oppose the trend, they took common cause with the radicals. Approximately 18,000 pounds (sterling) worth of East India Company tea was consigned to the deep in the Boston Tea Party (December 16, 1773). The citizens of other port towns were equally determined to frustrate the intent of the new British measure; some tea was destroyed, considerable quantities were locked up (and late sold to raise funds for the Revolutionary armies), and several shiploads were returned to England. From the English point of view, this was the critical challenge. Unless such rebelliousness was effectively punished, the whole colonial system would collapse. The effort to administer that punishment precipitated the military phase of the Revolution. IV. The Intolerable Acts The First Continental Congress The Boston Tea Party convinced the North ministry and Parliament that an example should be made of Massachusetts in an effort to bring all the colonies into obedience to law. Four laws, collectively denounced by the colonists as the “Intolerable Acts,” were passed by overwhelming majorities in the Spring of 1774. The Boston Port Act declared that the chief port of Massachusetts would be closed until the tea was paid for. This was disastrous to the prosperity of Boston. The Massachusetts Government Act revoked the colonial charter; forbade town meetings; and said that the council would be appointed by the governor instead of elected. The Act for the Impartial Administration of Justice allowed British officials charged with capital offences in connection with the suppression of riots or the enforcement of laws could be taken to England or to another colony for trial. The measure was designed to secure a fair trial of such cases, but the colonists denounced it as “The Murder Act.” The Quartering Act authorized the governors of all the colonies to requisition private buildings for the housing of troops when the available public quarters were insufficient. The Quebec Act was also passed by Parliament in 1774, and although the act had no immediate connection with the punitive measures against Massachusetts, certain of its provisions caused the colonists to include it among the “Intolerable Acts.” The act extended the boundary of Quebec to include the whole region between the Great Lakes and the Ohio River, a region to which many of the 13 colonies had claims under the terms of their original charters. This shift in boundaries gave the fur traders of Montreal an advantage in the Ohio Valley over those who operated from New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia. The provisional government which was established for Quebec did not include local self-government. While perhaps understandable, considering the French Canadians had no experience with self-government, to the colonists it seemed a precedent for encroachments upon their own liberties. The measures taken to enforce these laws were to the colonists as objectionable as the laws themselves. General Thomas Gage, the British commander in Boston, was named governor of Massachusetts, and several regiments of reinforcements were sent from England. At the time he assumed office, Gage had no doubt that order could be maintained; in common with almost every other British military leader at this time, he had a very low opinion of the fighting qualities of the colonists and of their capacity for united action. The Intolerable Acts and the troop movements made it clear to the colonists that Parliament had no intention of backing down again. The American radicals, who were similarly uninterested in compromising, found new allies because the punitive measures threatened both the economic and the political well-being of the colonies. In June 1774, the Virginia House of Burgesses, meeting unofficially after the governor had dissolved it for radicalism, invited all the colonies to send delegates to a meeting at Philadelphia. With the exception of Georgia, where the governor interfered, every colony was represented, either by appointees of the legislature or by men chosen by illegal mass meetings. Many of the ablest leaders in America were in the group that met in Carpenter‟s Hall, September 5, 1774. The 56 delegates were by no means of one mind as to a desirable line of action; in his diary, John Adams described them as being “one third Patriots, one third Tories, and one third “Mongrels.” However, they did agree on several moves: o A “Declaration of Rights and Grievances” was adopted. It elaborated the arguments against taxation without representation, and flatly denied the British doctrine of virtual representation. Arguments almost forgotten during the tranquil interlude from 1770-1773 were revived, and the final step was taken in the evolution of the colonial attitude—a complete rejection of the right of Parliament to levy taxes of any kind or for any purpose upon the colonies. The “Intolerable Acts” were denounced, and other grievances, real and fancied, were listed. o In communicating their views to the King and the English people, the congress denied any intent to seek independence, but stressed the urgency of a change of British policy. o For the more radical members of the congress, speeches and petitions were not enough. They secured the formation of a “Continental Association,” the purpose of which was to enforce a complete boycott of British goods until the injuries were redressed. “Committees of Safety” were formed to carry the boycott into effect. The measure was particularly effective in forcing the „Mongrels‟ to choose one side or the other. Nor could the choice be long delayed, for tar and feathers and other drastic penalties were inflicted upon boycott violators. Mass meetings in many communities endorsed the actions of the congress, and companies of local militia began to drill in anticipation of any eventuality. o Before adjourning, the delegates at Philadelphia provided for the meeting of a second Continental Congress in 1775 in the event the British position didn‟t change. Lord North made no official response to the statement of the congress, nor did he indicate any willingness to compromise. Edmund Burke, Pitt, and a few other Whigs urged compromise on minor matters, but no English leader was disposed to yield on any basic component of mercantilist colonial policy. North went so far as to offer to grant exemption from Parliamentary taxation to any colony that would voluntarily tax itself for colonial defense, but this gesture was unacceptable to the radicals in America, who were by now in control.