APRIL 02, 2014

THE NASDAQ COMPOSITE INDEX

A FOURTEEN-YEAR RETROSPECTIVE

DAVID KREIN | Head of Research • NASDAQ OMX Global Indexes

JEFFREY W. SMITH | Managing Director • NASDAQ OMX Economic Research

HIGHLIGHTS

The NASDAQ Composite continues to be a usefully distinct stock market metric that distinguishes itself from other broad indexes routinely

covered in the financial media.

Although the NASDAQ Composite has crossed 4000 again, a level last achieved in 1999, the index composition and valuation have experienced

dramatic changes during this 14-year period. The changes reflect trends that are NASDAQ-specific, but also reflect the macro forces impacting

the broader economy and capital markets.

The current index has about half the components it did 14 years ago (4,715 in 1999 versus 2,472 at the end of 2013). The current components,

though, are on average about twice the size as they were in 1999.

The majority of the securities (by index weight) that left the index since the end of 1999 did so as a result of merger and acquisition activity.

The current index is still strongly oriented towards the information technology sector, as it has always been. Currently 46% of the index by

weight is classified as Info Tech. The extent of technology orientation, however, appears to be receding.

Company valuations at the current index level are much more conservative than during the midst of the tech bubble of 1999/2000.

About 20% of current index weight (710 stocks) is from IPOs that NASDAQ brought to market during the last 14 years.

INTRODUCTION

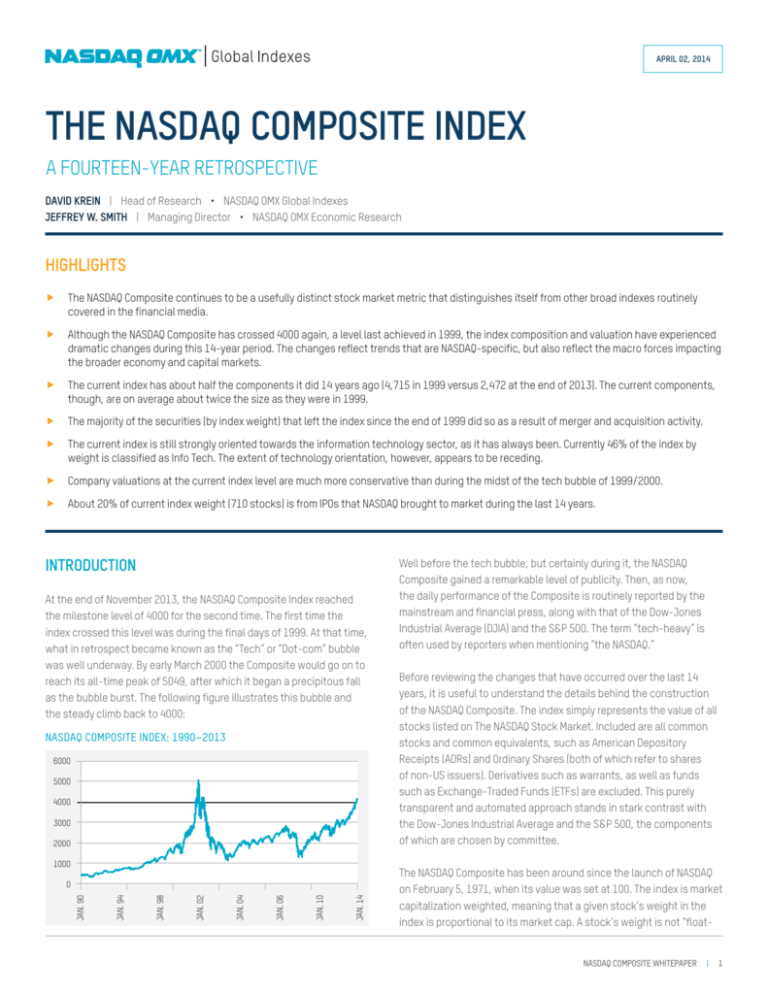

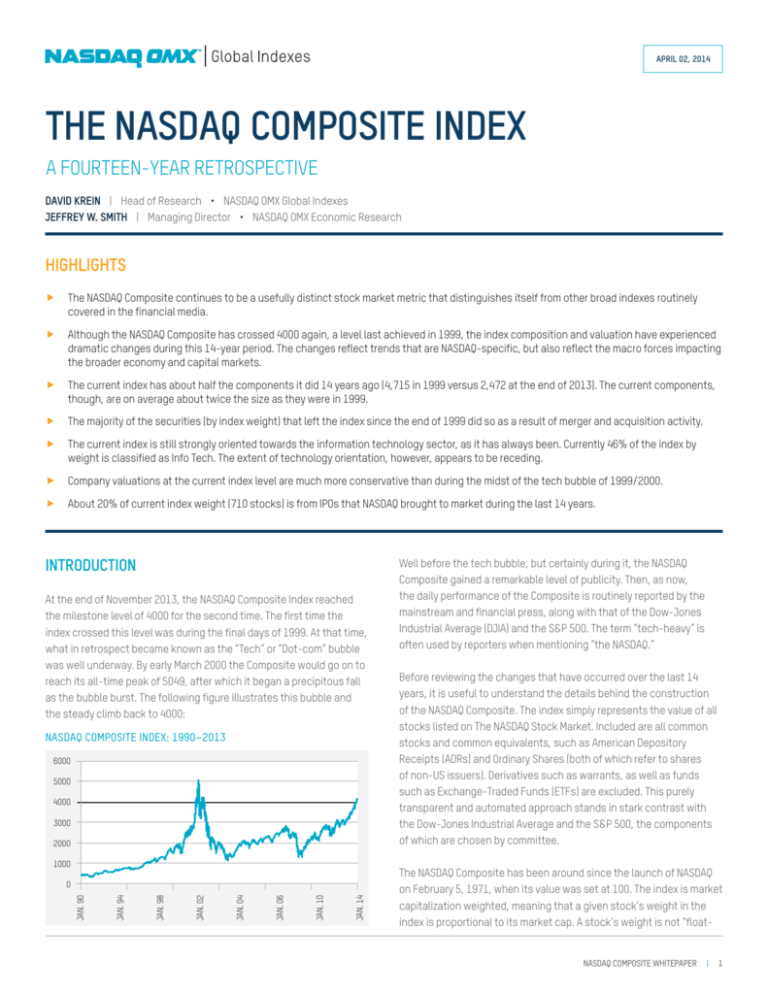

At the end of November 2013, the NASDAQ Composite Index reached

the milestone level of 4000 for the second time. The first time the

index crossed this level was during the final days of 1999. At that time,

what in retrospect became known as the “Tech” or “Dot-com” bubble

was well underway. By early March 2000 the Composite would go on to

reach its all-time peak of 5049, after which it began a precipitous fall

as the bubble burst. The following figure illustrates this bubble and

the steady climb back to 4000:

NASDAQ COMPOSITE INDEX: 1990–2013

6000

5000

4000

3000

2000

1000

JAN. 14

JAN. 10

JAN. 06

JAN. 04

JAN. 02

JAN. 98

JAN. 94

JAN. 90

0

Well before the tech bubble, but certainly during it, the NASDAQ

Composite gained a remarkable level of publicity. Then, as now,

the daily performance of the Composite is routinely reported by the

mainstream and financial press, along with that of the Dow-Jones

Industrial Average (DJIA) and the S&P 500. The term “tech-heavy” is

often used by reporters when mentioning “the NASDAQ.”

Before reviewing the changes that have occurred over the last 14

years, it is useful to understand the details behind the construction

of the NASDAQ Composite. The index simply represents the value of all

stocks listed on The NASDAQ Stock Market. Included are all common

stocks and common equivalents, such as American Depository

Receipts (ADRs) and Ordinary Shares (both of which refer to shares

of non-US issuers). Derivatives such as warrants, as well as funds

such as Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) are excluded. This purely

transparent and automated approach stands in stark contrast with

the Dow-Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500, the components

of which are chosen by committee.

The NASDAQ Composite has been around since the launch of NASDAQ

on February 5, 1971, when its value was set at 100. The index is market

capitalization weighted, meaning that a given stock’s weight in the

index is proportional to its market cap. A stock’s weight is not “float-

NASDAQ COMPOSITE WHITEPAPER

|

1

adjusted,” i.e., reduced to account for shares not available to trade by

the investment community. (Specific index rules are in a methodology

document available at indexes.NASDAQOMX.com/docs/methodology_

COMP.pdf.)

The NASDAQ Composite should not be confused with another wellknown NASDAQ index, the NASDAQ-100. The latter is made up of the

top 100 non-financial companies listed on NASDAQ. It began in 1985,

and uses an adjusted market cap weighting method that ensures

that no single component of the index carries too much weight. It is

interesting to note that while the Composite receives the majority of

the coverage in the financial press, the NASDAQ-100 is much more

prominent in terms of having financial products tied to it. Indeed, the

NASDAQ-100 is specifically designed and maintained to provide the

basis for financial products. For example, one of the largest ETFs in

the world, the PowerShares QQQ, is benchmarked to the NASDAQ-100.

The NASDAQ-100 also has a wide array of futures, options, and

other products tied to it. As with the Composite, the NASDAQ-100’s

components are not chosen by committee, but by a set of distinct

eligibility criteria and rules-based methodology.

The striking conclusion of the table is that the current index has 48%

fewer components as before, but these components are nearly 120%

larger than before on average. Also worth noting, while the value of

the index at the two points of comparison are about equal, the market

capitalization is 15% higher. This change is due to increases in shares

of the listed companies, not increases in prices.

The results of Table 1 reflect a national trend that extends beyond

NASDAQ—a shrinking number of listed public companies. The following

graph shows the number of common stocks listed on the three US

listing venues: NASDAQ, NYSE, and NYSE MKT (formerly the American

Stock Exchange). The graph illustrates a remarkably steady decline;

the end result being that the number of listings is about half of what

it was at the start of the 2000s. The causes of this trend and whether

capital markets are better or worse off as a result is a fascinating

question beyond the scope of this paper.

NUMBER OF LISTED U.S. COMMON STOCKS

LISTING VENUES: NASDAQ, NYSE, NYSE MKT

In fact, there are so many changes that have occurred in this 14year period that analyses from several perspectives are warranted

and worthwhile.

2014

2012

2010

2008

2006

4000

Table 2 shows the identity and market capitalizations of the top

ten components.

TABLE 2: TOP 10 COMPONENTS THEN AND NOW

12/31/99

12/31/13

MKT CAP

($BLNS)

STOCK

MKT CAP

($BLNS)

MICROSOFT

$606

APPLE

$505

CISCO

$360

MICROSOFT

$312

QUALCOMM

$332

GOOGLE

$310

INTEL

$277

AMAZON

$182

WORLDCOM

$228

INTEL

$129

RATIO

ORACLE

$151

QUALCOMM

$125

$132

CISCO

$120

Table 1 shows the total number of index components at the end of

1999 and the end of 2013. Also shown are the total market cap of the

components and the average market cap per component.

TABLE 1: COMPONENTS OF COMPOSITE INDEX

DEC 31,

2013

5000

STOCK

COMPONENT COMPOSITIONS

DEC 31,

1999

6000

2004

However, over longer time periods such as the last 14 years, the

component stocks do change in very significant ways. This means

observers cannot easily interpret the significance of NASDAQ 4000

then versus NASDAQ 4000 now.

7000

2002

From day-to-day, changes in the level of the NASDAQ Composite (or no

change at all) are reflective of the changes in value of the component

stocks. Observers can easily interpret the NASDAQ at 4000, then 4001,

then 4010, and so on. This is because the components, over such

short time periods, don’t change very much, except for their prices.

8000

2000

THE CHANGING NATURE OF THE COMPOSITE INDEX

NUMBER OF STOCKS AT MID-YEAR

9000

VALUE OF INDEX

4069

4177

1.03

DELL

NUMBER OF COMPONENTS

4,715

2,472

0.52

SUN MICROSYSTEMS

$117

GILEAD SCIENCES

$115

TOTAL MARKET CAP ($B)

$5,453

$6,271

1.15

YAHOO

$103

COMCAST

$111

AVG MARKET CAP ($MM)

$1,157

$2,537

2.19

JDS UNIPHASE

$75

FACEBOOK

$102

NASDAQ COMPOSITE WHITEPAPER

|

2

The top four companies of 1999 still appear in 2013, but their

aggregate market value is 44% of what it was then. The fifth company,

WorldCom, went bankrupt in 2002. The combined reduction in market

cap of these five securities is about $1.1 trillion, which is nearly 20%

of NASDAQ’s total market cap in 1999. In fact, exclusive of these five

stocks, the average market cap per stock rose from $774 million to

$2.26 billion, an increase of 192%.

The table shows why the index is strongly associated with the

technology sector, both in 1999 and currently. It is interesting to

see, however, in the current top 10 list the emergence of marquee

companies not in the Information Technology sector: Amazon in

retailing, Gilead in biotech, and Comcast in media. Also noteworthy is

the presence of the largest social networking company, Facebook.

Overall, while some names have changed, there can be no doubt

that the NASDAQ Composite index’s top components have historically

featured companies that are known for innovation and growth.

NATURE OF DELETIONS

As the preceding tables illustrate, there has been substantial change

in the composition of the index as well as a reduction of about onehalf in the number of components from 2000. What has happened to

the companies present in 1999 but no longer in the index?

TABLE 3: DISPOSITION OF INDEX COMPONENTS PRESENT AT END OF 1999

NUMBER

TOTAL MKT CAP AT

END OF 1999 ($T)

ALL

4,715

$5.43

VETERANS TO END OF 2013

1023 (22%)

$2.89 (53%)

DELETED BY END OF 2013

3692 (78%)

$2.57 (47%)

About 53% of the market value of the index, drawn from 1,023 issues,

has lasted 14 years to continue to be in the index. The other half of

market value, made up of almost 3,700 issues, representing 78%

of the stocks on NASDAQ at the time, have left the index. Given the

numbers, it is clear that the deletions tended to be smaller on average

than the veterans ($696 million versus $2.82 billion).

NASDAQ tracks the cause behind these deletions, summarized as follows:

TABLE 4: REASON FOR NASDAQ DELETIONS

NO. STOCKS PCT MKT CAP

MERGER/ACQUISITION

1786

53.9%

REGULATORY NON-COMPLIANCE

674

17.4%

VOLUNTARY DELISTING

812

25.0%

MOVED TO OTC

109

1.3%

OTHER

311

2.4%

TOTAL

3692

100.0%

Most interesting to note is that 54% of the stocks by market cap

(and 46% by number of deleted stocks) were removed due to merger

and acquisition activity. This runs counter to the popular belief that

in the collapse of the tech bubble most of the NASDAQ stocks were

“dot-coms” and deleted due to bankruptcy. This is, in fact, not the

case at all.

This M&A activity is consistent with a general theme of a market of

fewer but larger public companies. Within the M&A category there are

several possible outcomes:

a. Both acquirer and target are listed on NASDAQ and the combined

entity remains listed on NASDAQ. This would reduce the number of

NASDAQ-listed companies, but would not result in a reduction in the

market cap of listings. (Presumably the market cap of the combined

entity is roughly the sum of the two companies individually.)

b. E

ither the acquirer or target is listed on NASDAQ, and the combined

entity leaves NASDAQ. This would reduce the number of NASDAQlisted companies and would reduce the market cap of listings.

More than 17% of deletions (in terms of value) was a result of

companies failing to meet listing standards as a result of declining

business prospects, including bankruptcy. The largest company in

this category was telecommunications firm WorldCom. This company’s

demise, along with that of NYSE-listed Enron, was a key trigger behind

the Sarbanes-Oxley reforms of 2002 mandating tighter financial

management and reporting for public companies. The failure of many

of the dot-coms was a trigger for another regulatory reform—the

Global Securities Analyst Settlement of 2003. This settlement sought

to ensure that research from securities analysts was not conflicted by

investment banking relationships.

A comparatively small amount of lost market cap was due to

companies delisting for reasons other than being forced to

delist. An example of this case concerns ADR programs that were

cancelled by the (foreign) issuer. Another small group of companies

left NASDAQ but continued to trade on the Over-the-Counter (OTC)

market. While not representing an outright cessation of trading, this

demotion to OTC trading was typically the result of an inability to

meet listing standards.

ADDITIONS TO INDEX

As a flip side to the deletions, analysis of additions to the NASDAQ

Composite index can also be considered. The following table provides

this information.

NASDAQ COMPOSITE WHITEPAPER

|

3

TABLE 5: SOURCES OF NASDAQ COMPONENTS SINCE 1999 AS OF END

OF 2013

CHANGING PROFILE

NUMBER

PCT OF MKT CAP

END OF 2013

VETERANS

1023

61.2%

IPOS

710

19.8%

COMPANY AGE

SWITCHES FROM OTHER EXCHANGES

147

10.8%

UPGRADES FROM OTC

298

1.7%

OTHER

294

6.5%

TOTAL

2472

100.0%

NASDAQ has always been thought of as the home of younger

companies. In fact, it also contains a number of companies dating

to the 19th century, many of which are community banks (among

the oldest is Hingham Institution for Savings, founded in 1834). On a

market-cap weighted basis, however, NASDAQ tends to be a market of

younger, growth-oriented companies. Consider the “median marketcap weighted age,” defined such that half the index market cap is

made up of companies older, and half younger, than this median

age. For this analysis, age is defined as time from incorporation,

not the time from IPO or initial listing. For, example, Facebook was

incorporated in 2004 but did not have its IPO until 2012. As of the end

of 2013, therefore, its age was nine years.

The majority of the current value of the Composite is from companies

that were in the index in 1999. These 1,023 veterans, which are 61%

of the current index value and 41% by number of stocks, have an

average size of $3.8 billion, while in 1999 their average value was

$2.8 billion.

It is interesting to note how these figures look without the top four

of 1999: Microsoft, Intel, Cisco, and Qualcomm. In 1999, the 1,019

surviving stocks had a market cap of $1.3 trillion; those same 1,019

veterans had a market cap of $3.2 trillion at the end of 2013, an

increase of 140% (versus 33% when the top four are included).

The largest source of additions has been IPOs. Over the last 14 years

NASDAQ has brought to market 710 stocks that are still listed on

NASDAQ today. Perhaps the most prominent among them are Google

and Facebook, but there are many other easily recognizable names.

Transfers from the NYSE and NYSE MKT totaled 147 and account for

about 11% of market value. Most of these transfers have occurred

from 2008 forward. Some of the larger switches from NYSE are

Twenty-First Century Fox (formerly News Corp), Texas Instruments,

and Automatic Data Processing (ADP). Note the large average size

of these transfers. The size and number of switchers illustrate

a competitive dimension to listings, with moves going in both

directions.

A comparatively small group of additions have joined the NASDAQ

Composite by upgrading from the OTC world. Finally, some companies

have joined by other means, typically through some type of

corporate action such as a spinoff. A recent example is the listing of

Kraft Foods, which was spun off of Mondelez (itself originally known

as Kraft). Another example is the parent company of NASDAQ itself,

the NASDAQ OMX Group, which was carved out of the old National

Association of Securities Dealers (NASD), a regulatory body, and

never came to market as an IPO.

The large number of changes in component stocks over time has

begun to shift the profile of the Composite in meaningful ways.

TABLE 6: MARKET CAP MEDIAN AGE OF NASDAQ COMPANIES

DEC 31, 1999

DEC 31, 2013

15.1 YEARS

25.0 YEARS

All else equal, a mature steady-state capital market would be

expected to have a natural cycle of company births and deaths

leading to a constant median age. On NASDAQ, however, in 14 years,

the median age went up 10 years, indicating substantial maturation.

The age of veterans and new additions as of the end of 2013 is shown

in the next table.

TABLE 7: MARKET CAP MEDIAN AGE OF COMPOSITE COMPONENTS AS OF

END OF 2013

MEDIAN AGE (YEARS)

VETERANS

36.9

IPOS

13.9

SWITCHERS (EXCHANGE + OTC)

16.9

OTHER

14.2

Not surprisingly, the veterans are the oldest group, their age being

exactly 14 years older than it was in 1999. Even at 37 years, however,

the veterans are still young companies. Also not surprising is the low

median age of the IPOs. The switchers are perhaps surprisingly young.

This finding suggests that younger companies are the most likely to

switch to NASDAQ. Interpreting the age of the “Other” group is difficult,

since the event that caused the company to be listed in the first place

may be closely tied to its birth (for example, a coincident spin-off and

NASDAQ listing).

NASDAQ COMPOSITE WHITEPAPER

|

4

In all cases, the additions to the NASDAQ Composite during the last 14

years have been younger than the incumbents, keeping the median

age lower than it otherwise would have been under natural aging.

TABLE 9: GICS SECTOR OF COMPOSITE COMPONENTS

PCT MARKET CAP

GICS SECTOR

VETERANS

IPOS

COMPANY INDUSTRY

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

50%

56%

28%

11%

As mentioned previously, the NASDAQ Composite Index is generally

associated with various High-Technology sectors, Information

Technology in particular. In comparing the industry orientation of

NASDAQ between now and 14 years ago, the only available measure of

industry is the Standard Industry Classification (SIC) system of the US

government. With these definitions, the top SIC industries (at the fourdigit level) now and then are shown in the following table.

CONSUMER DISCRETIONARY

16%

15%

33%

47%

HEALTH CARE

17%

14%

5%

13%

FINANCIALS

7%

5%

9%

11%

INDUSTRIALS

5%

5%

3%

7%

CONSUMER STAPLES

3%

1%

9%

8%

TELECOMMUNICATION

SERVICES

0%

0%

10%

1%

ENERGY

0%

3%

2%

2%

MATERIALS

1%

1%

1%

1%

UTILITIES

0%

0%

0%

0%

TABLE 8: TOP SIC INDUSTRIES LISTED ON NASDAQ

End of 1999

SIC INDUSTRY

End of 2013

PCT OF

MKT CAP

SIC INDUSTRY

PCT OF

MKT CAP

SWITCHES OTHERS

PREPACKAGED

SOFTWARE

23%

PREPACKAGED

SOFTWARE

10%

SEMICONDUCTORS

10%

ELECTRONIC

COMPUTERS

9%

COMPUTER

PERIPHERALS

8%

SEMICONDUCTORS

9%

TELECOM

7%

INFORMATION

RETRIEVAL

6%

Analysis of GICS sectors again confirms the strong IT orientation of the

NASDAQ Composite, with about half of the NASDAQ Composite’s market

cap in the GICS IT Sector. The IPO additions to the Composite have a

sector profile very similar to that of the veterans. Quite interestingly,

however, is the fact that the other additions to the NASDAQ Composite

do not have the same level of technology orientation. The net result

is that the current the NASDAQ Composite has evolved with a lower

technology tilt than before.

ELECTRONIC

COMPUTERS

5%

BIOLOGICAL

PRODUCTS

6%

VALUATION

COMPUTER SYSTEMS

3%

CABLE TELEVISION

5%

TELEPHONE

APPARATUS

3%

PHARMACEUTICAL

4%

A hallmark of the 1990s bubble was the sky-high valuation levels of

NASDAQ-listed companies. The following table shows price/earnings

ratios then and now for a selection of marquee companies.

ALL INFO TECH

57%

ALL INFO TECH

38%

TABLE 10: PRICE/EARNINGS RATIOS OF SELECTED COMPANIES

Figures in the Table 8 provide clear justification for NASDAQ’s tech

reputation. However, comparing the two periods suggests that the

current NASDAQ is less tech heavy than in 1999. The sum of all SIC

industries that may be considered “Information Technology” indicates

a decline in terms of percentage of market cap from 57% to 38%.

Again, one can consider the impact of deletions and additions on

the evolution of NASDAQ’s industry orientation. Instead of using the

SIC system, it is preferable to use a proprietary classification system

that is more up-to-date and better designed for the use of investors.

One such system is the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS)

system offered by Standard and Poor’s. The following table shows the

sector breakdown of current components of the NASDAQ Composite.

STOCK

END OF 1999

END OF 2013

MICROSOFT

73

13

INTEL

35

14

CISCO

166

13

APPLE

37

14

QUALCOMM

224

19

YAHOO

787

35

The 2013 values of the P/E ratio are much lower relative to their 1999

values. Many components of the NASDAQ Composite in 1999 had no

P/E ratio, owing to a lack of earnings.

Using its proprietary analytics, Bloomberg provides a number of

valuation metrics for indexes as a whole. Here is a set of such metrics

for the NASDAQ Composite index.

NASDAQ COMPOSITE WHITEPAPER

|

5

THREE INDEXES DURING TECH BUBBLE

END OF 1999

END OF 2013

PRICE/EARNINGS

152

31

7000

PRICE/BOOK

6.7

3.9

6000

DIVIDEND YIELD

0.11%

1.22%

5000

INDEX EARNINGS

27

133

4000

The typical NASDAQ stock in 1999 did not pay dividends. Companies of

that era were in full-tilt growth mode, and to the extent that earnings

were returned to shareholders, it was in the form of share buybacks.

That is much less true of the current NASDAQ-listed companies. A

good example is long-time dividend holdout Apple, which started

paying a regular quarterly dividend only since 2012.

The NASDAQ-listed companies of 1999 were not necessarily very

profitable—high earnings were expected for the future. The Bloomberg

“Index Earnings” metric is determined by taking aggregate earnings

for the set of components and dividing by the index divisor. This step

allows one to compare earnings for a fixed level of shares (just like

the price index does). This metric indicates 2013 earnings that are

almost five times higher than they were in 1999 for the same number

of shares.

In sum we see a current NASDAQ Composite more conservatively

valued and more profitable than it was in 1999.

NQ COMP DJIA

3000

2000

1000

DEC. 02

JAN. 02

JAN. 01

JAN. 00

JAN. 99

JAN. 98

JAN. 97

0

JAN. 95

The 1999 P/E ratio—again with the benefit of hindsight—seems

otherworldly for such a broad index with more than 4,700 constituents.

Today, it is now at a much more conservative level, though the current

value is still higher than what would be expected for most stocks

(more on this below). The same may be said of the Price/Book ratio.

SP 500

01 JAN 1995 = 1000

JAN. 96

TABLE 11: BLOOMBERG VALUATION METRICS FOR NASDAQ COMPOSITE

While all three indexes rose then fell during the bubble, the pattern of

the NASDAQ Composite deviates from the others in spectacular fashion.

The next graphic shows the performance of the same three indexes

starting in 2005, before the financial crisis and current bull market (all

three indexes rebased to the same value at the start of 2005).

THREE INDEXES DURING CURRENT BULL MARKET

SP 500

01 JAN 2005 = 1000

NQ COMP DJIA

2000

1750

1500

1250

1000

750

PERFORMANCE

A couple of graphical illustrations are useful. First, consider the

Composite compared with the DJIA and S&P 500 before and after the

tech bubble. Note that the following graph rebases all three indexes

so they have a value of 1000 at the start of 1995.

DEC. 13

JAN. 13

JAN. 11

JAN. 09

JAN. 07

The foregoing material showed the NASDAQ Composite of today to be a

more mature, more profitable, and slightly less tech-heavy index than

it was 14 years ago. These changes lead directly to the questions: If

the NASDAQ Composite was different than the other indexes in the

past, is it still so today? Does it still warrant separate mention in the

media and investors’ minds?

500

JAN. 05

NASDAQ COMPOSITE VS. OTHER BROAD INDEXES

During the bull market that preceded the financial crisis, and during

the crisis itself, all three indexes tracked fairly closely. Since the start

of the recovery in 2009, all three indexes have rebounded to precrisis levels, and then continued to grow. However, the Composite,

has clearly grown faster since the trough, indicating some level

of differentiation. So, while the Composite has tracked the other

indexes more closely than during the tech bubble, there is still some

differentiation today.

LONG-TERM PERFORMANCE CHARACTERISTICS

For assessing the long-term characteristics of a set of indexes, it

is important to consider a time frame long enough to span the tech

NASDAQ COMPOSITE WHITEPAPER

|

6

bubble/bust and the financial crisis of 2008. The following table

provides information on the Composite along with four other broad

indexes over a 24-year period, starting in 1990. Included in the list of

alternative indexes is the NASDAQ-100.

TABLE 12: PERFORMANCE STATISTICS SINCE 1990

NQ

COMP

S&P

500

AVG ANNUAL PRICE

RETURN

9.58%

7.03%

AVG ANNUAL TOTAL

RETURN

10.22% 9.41% 10.43% 12.65%

METRIC

DJIA

NQ

100

RUSSELL

3000

7.64% 12.18% 7.35%

N/A

STD DEV DAILY PRICE

RETURNS

1.52%

1.16%

1.10%

1.80%

1.16%

CORRELATION W/ COMP

1

0.87

0.78

0.97

0.89

CURRENT MKT CAP ($T)

$6.50

$17.10

$4.70

$4.10

$21.50

chart illustrates the correlation of returns between the NASDAQ

Composite and the other alternatives. It shows, for a date indicated

on the horizontal axis, the correlation between daily returns on

the Composite and the alternative for the previous 12 months. The

correlation is therefore a rolling measure showing how it has evolved

over the years. (Recall that a correlation of one would mean two

indexes move in perfect lockstep, while correlation of zero means

there is no relationship.)

ROLLING CORRELATION OF DAILY RETURNS WITH NQ COMPOSITE

SP 500 NQ 100 DJIA RUSSELL 3000

TRAILING 12 MONTHS

1.0

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

In terms of short-term price risk, the two NASDAQ indexes have

exhibited higher volatility than the others. Given what has been

covered in this paper, this result is not surprising. Indeed, in the

specific case of the NASDAQ-100 index, one can see the exceptional

growth opportunities that were available during this time frame, albeit

at the price of higher risk.

In terms of correlations of daily returns we see the expected very high

correlation between the Composite and its close sibling NASDAQ-100.

We see much less correlation with the other broad indexes,

particularly with the DJIA. Again this is not unexpected as the NASDAQ

Composite and the DJIA may be considered largely at opposite ends

of the spectrum: the DJIA representing mature blue chips, the NASDAQ

Composite young growth companies. (Recognizing, though, that the

DJIA contains three NASDAQ stocks: Microsoft, Intel, and Cisco.)

The table also shows the current market cap coverage of each index,

showing the comparatively small coverage of indexes like the DJIA and

NASDAQ-100. The Russell 3000 essentially covers the totality of the US

equity market, thereby allowing one to compare the various indexes

against the entire market.

0.5

0.4

JAN. 14

JAN. 12

JAN. 09

JAN. 06

JAN. 03

JAN. 00

JAN. 97

JAN. 94

0.3

JAN. 91

The table provides two measures of average return: those based

on prices only, and those that include dividends (assumed invested

into the index). During this time frame, the NASDAQ-100 provided the

highest average return, both in terms of price returns as well as the

total returns. Note the relatively large difference in price and total

return for the DJIA, due to a comparatively large dividend yield for

DJIA components.

The graph shows, not surprisingly, a high correlation between

the NASDAQ Composite and the NASDAQ-100. There is much less

correlation with the other indexes, particularly during the 1990s.

The peak of the tech bubble in 2000 marked a point of relatively

low correlation with the DJIA. Since that time, the correlations with

the NASDAQ Composite have increased. During the financial crisis,

correlations were quite high. During the following recovery and bull

market, correlations have fallen a bit, particularly for the DJIA.

The next chart shows annualized daily return standard deviations, again

using the same trailing 12-month method as the previous chart.

ROLLING ANNUALIZED RETURN STANDARD DEVIATION

TRAILING 12 MONTHS

SP 500 NQ COMP NQ 100 DJIA RUSSELL 3000

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

NASDAQ COMPOSITE WHITEPAPER

JAN. 14

JAN. 12

JAN. 09

JAN. 06

JAN. 03

JAN. 00

JAN. 97

JAN. 94

0

JAN. 91

While these performance statistics provide interesting historical

perspective, their forward-looking value may be limited due to the

changing nature of the NASDAQ Composite as documented above.

Consider for example the correlation of daily returns. The following

|

7

During the 1990s, the two NASDAQ indexes were clearly more volatile

than the others, particularly during the tech bubble and its aftermath.

Since that time, there has been greater uniformity in volatility. For

example, the uniformity increases during the financial crisis impacting

all the indexes.

Consider now three dimensions on which the Composite can be

compared with the other broad indexes: industry orientation, company

age, and current valuation metrics. Significant differences between

the NASDAQ Composite and the other indexes remain.

The first is a comparison of industry orientation, as measured using

the GICS system.

TABLE 13: MARKET CAP BREAKDOWN BY GICS SECTOR

PCT OF MARKET CAP

GICS SECTOR

NQ COMP

S&P 500

DJIA

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

46%

18%

19%

CONSUMER DISCRETIONARY

20%

13%

13%

HEALTH CARE

15%

13%

10%

FINANCIALS

7%

16%

16%

INDUSTRIALS

4%

11%

20%

CONSUMER STAPLES

4%

10%

8%

TELECOMMUNICATION SERVICES

2%

2%

3%

ENERGY

1%

10%

9%

MATERIALS

1%

3%

2%

UTILITIES

0%

3%

0%

The NASDAQ Composite continues to stand out for its high

representation in the IT sector and low representation in other

sectors, such as Industrials, Energy, and Utilities. While we have

seen that “tech-heavy” is perhaps less appropriate than it was in

1999, the term still fits when comparing the NASDAQ Composite with

other broad indexes.

Consider now company age. FactSet Data Systems provides the year

of company founding for all US stocks. The following table provides

weighted median founding years. For the NASDAQ Composite and

S&P 500, market caps were used as the weighting. This means that

for the indicated median, half of the market cap is from companies

founded after that year, half before that year. For the DJIA, which is a

price-weighted index, the weights are the closing prices of the index

components (as of the end of 2013).

TABLE 14: INDEX-WEIGHTED MEDIAN YEAR OF FOUNDING

INDEX

YEAR

NQ COMPOSITE

1985

NQ 100

1984

S&P 500

1958

RUSSELL 3000

1968

DJIA

1908

The NASDAQ Composite (and NASDAQ-100) exhibit higher valuation

multiples than the other indexes. Composite components

continue to pay fewer dividends, and are a bit less profitable than

components of the other indexes. These metrics are consistent with

the idea that the NASDAQ Composite is more representative of the

growth sector of the economy.

In sum, there is no doubt that the differences in the NASDAQ

Composite and other broad indexes are not as substantial as they

were during the height of the tech bubble 14 years ago. The NASDAQ

Composite, however, continues to differentiate itself as the home to

companies that are younger and more growth oriented.

DATA SOURCES

The data used in most of the analyses presented in this paper are from

various internal NASDAQ OMX sources. NASDAQ OMX maintains detailed

information on its listings. It also maintains extensive databases of

pricing information for individual securities and indexes.

Tables 9 and 13 use Standard and Poor’s GICS sector classification as

provided by Bloomberg.

Tables 10 and 11 use valuation data provided by Bloomberg.

The average price and total return values in Table 12 are provided by Bloomberg.

The results in Table 14 are based on data provided by FactSet Data Systems.

Data used in the charts and elsewhere in this paper are from internal NASDAQ OMX

sources, Bloomberg, FactSet, or Yahoo Finance.

DISCLAIMER

NASDAQ® ,and NASDAQ OMX®, NASDAQ-100®, NASDAQ-100 Index®,

NASDAQ Composite®, NASDAQ Composite Index®, and The NASDAQ Stock

Market® are all registered trademarks of The NASDAQ OMX Group, Inc.

The information contained above is provided for informational and

educational purposes only, and nothing contained herein should

be construed as investment advice, either on behalf of a particular

security or an overall investment strategy. Neither The NASDAQ OMX

Group, Inc. nor any of its affiliates makes any recommendation to buy

or sell any security or any representation about the financial condition

of any company. Statements regarding NASDAQ-listed companies or

NASDAQ proprietary indexes are not guarantees of future performance.

Actual results may differ materially from those expressed or implied.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. Investors should

undertake their own due diligence and carefully evaluate companies

before investing. ADVICE FROM A SECURITIES PROFESSIONAL IS

STRONGLY ADVISED.

© COPYRIGHT 2014. THE NASDAQ OMX GROUP, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NASDAQ OMX AND NASDAQ ARE REGISTERED SERVICE/

TRADEMARKS OF THE NASDAQ OMX GROUP, INC. Q14-0618