Mary Elizabeth Lease - Kansas Historical Society

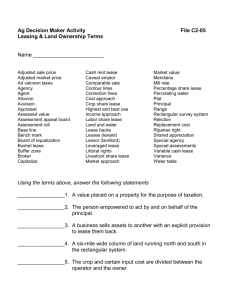

advertisement