The Story \"Everyday Use\" is narrated by a woman who descr

advertisement

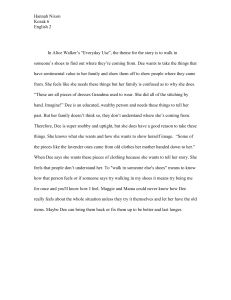

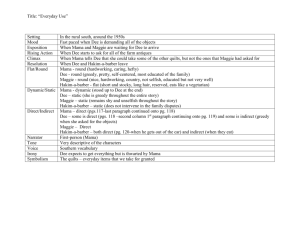

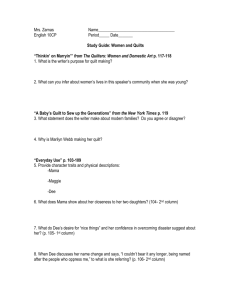

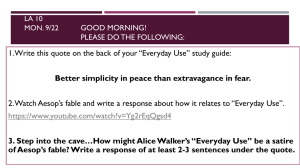

The Story "Everyday Use" is narrated by a woman who describes herself as "a large, big-boned woman with rough, man-working hands." She has enjoyed a rugged farming life in the country and now lives i n a small, tin-roofed house surrounded by a clay yard in the middle of a cow pasture. She anticipate s that soon her daughter Maggie will be married and she will be living peacefully alone. The story opens as the two women await a visit from the older daughter, Dee, and a man who may be her husband-her mother is not sure whether they are actually married. Dee, who was always scornful of her famil y's way of life, has gone to college and now seems almost as distant as a film star; her mother imag ines being reunited with her on a television show such as "This Is Your Life," where the celebrity g uest is confronted with her humble origins. Maggie, who is not bright and who bears severe burn scar s from a house fire many years before, is even more intimidated by her glamorous sibling. To her mo ther's surprise, Dee arrives wearing an ankle-length, gold and orange dress, jangling golden earring s and bracelets, and hair that "stands straight up like the wool on a sheep." She greets them with a n African salutation, while her companion offers a Muslim greeting and tries to give Maggie a ceremo nial handshake that she does not understand. Moreover, Dee says that she has changed her name to Wan gero Leewanika Kemanjo, because "I couldn't bear it any longer, being named after the people who opp ress me." Dee's friend has an unpronounceable name, which the mother finally reduces to "Hakim-a-bar ber." As a Muslim, he will not eat the pork that she has prepared for their meal. Whereas Dee had b een scornful of her mother's house and possessions when she was younger (even seeming happy when the old house burned down), now she is delighted by the old way of life. She takes photographs of the h ouse, including a cow that wanders by, and asks her mother if she may have the old butter churn whit tled by her uncle; she plans to use it as a centerpiece for her table. Then her attention is capture d by two old handmade quilts, pieced by Grandma Dee and quilted by the mother and her own sister, kn own as Big Dee. These quilts have already been promised to Maggie, however, to take with her into he r new marriage. Dee is horrified: "Maggie can't appreciate these quilts!" she says, "She'd probably be backward enough to put them to everyday use." Although Maggie is intimidated enough to surrender the beloved quilts to Dee, the mother feels a sudden surge of rebellion. Snatching the quilts from Dee, she offers her instead some of the machine-stitched ones, which Dee does not want. Dee turns to leave and in parting tells Maggie, "It's really a new day for us. But from the way you and Mama sti ll live you'd never know it." Maggie and her mother spend the rest of the evening sitting in the yar d, dipping snuff and "just enjoying." Themes and Meanings The central theme of the story concerns the way in which an individual understands his present life in relation to the traditions of his peo ple and culture. Dee tells her mother and Maggie that they do not understand their "heritage," becau se they plan to put "priceless" heirloom quilts to "everyday use." The story makes clear that Dee is equally confused about the nature of her inheritance both from her immediate family and from the la rger black tradition. The matter of Dee's name provides a good example of this confusion. Evidently , Dee has chosen her new name ("Wangero Leewanika Kemanjo") to express solidarity with her African a ncestors and to reject the oppression implied by the taking on of American names by black slaves. To her mother, the name "Dee" is symbolic of family unity; after all, she can trace it back to the tim e of the Civil War. To the mother, these names are significant because they belong to particular bel oved individuals. Dee's confusion about the meaning of her heritage also emerges in her attitude to ward the quilts and other household items. While she now rejects the names of her immediate ancestor s, she eagerly values their old handmade goods, such as the hand-carved benches made for the table w hen the family could not afford to buy chairs. To Dee, artifacts such as the benches or the quilts a re strictly aesthetic objects. It never occurs to her that they, too, are symbols of oppression: Her family made these things because they could not afford to buy them. Her admiration for them now see ms to reflect a cultural trend toward valuing handmade objects, rather than any sincere interest in her "heritage." After all, when she was offered a quilt before she went away to college, she rejecte d it as "old-fashioned, out of style." Yet a careful reading of the story will show that Dee is not the only one confused about the heritage of the black woman in the rural South. Although the mother and Maggie are skeptical of Dee, they recognize the limitations of their own lives. The mother has only a second-grade education and admits that she cannot imagine looking a strange white man in the eye. Maggie "knows she is not bright" and walks with a sidelong shuffle. Although their dispositions lead them to make the best of their lives, they admire Dee's fierce pride even as they feel the for ce of her scorn. Taken as a whole, while the story clearly endorses the commonsense perspective of Dee's mother over Dee's affectations, it does not disdain Dee's struggle to move beyond the limited world of her youth. Clearly, however, she has not yet arrived at a stage of self-understanding. Her mother and sister are ahead of her in that respect. Style and Technique The thematic richness of " Everyday Use" is made possible by the flexible, perceptive voice of the first-person narrator. It is the mother's point of view which permits the reader's understanding of both Dee and Maggie. Seen fr om a greater distance, both young women might seem stereotypical--one a smart but ruthless college g irl, the other a sweet but ineffectual homebody. The mother's close scrutiny redeems Dee and Maggie, as characters, from banality. For example, Maggie's shyness is explained in terms of the terrible fire she survived: "Sometimes I can still hear the flames and feel Maggie's arms sticking to me, her hair smoking and her dress falling off her in little black papery flakes. Her eyes seemed stretched open, blazed open by the flames reflected in them." Ever since, "she has been like this, chin on ch est, eyes on ground, feet in shuffle." In Dee's case, the reader learns that, as she was growing up the high demands she made of others tended to drive people away. She had few friends, and her one bo yfriend "flew to marry a cheap city girl from a family of ignorant flashy people" after Dee "turned all her faultfinding power on him." Her drive for a better life has cost Dee dearly, and her mother' s commentary reveals that Dee, too, has scars, though they are less visible than Maggie's. In addit ion to the skillful use of point of view, "Everyday Use" is enriched by Alice Walker's development o f symbols. In particular, the contested quilts become symbolic of the story's theme; in a sense, the y represent the past of the women in the family. Worked on by two generations, they contain bits of fabric from even earlier eras, including a scrap of a Civil War uniform worn by Great Grandpa Ezra. The debate over how the quilts should be treated--used or hung on the wall--summarizes the black wom an's dilemma about how to face the future. Can her life be seen as continuous with that of her ances tors? For Maggie, the answer is yes. Not only will she use the quilts, but also she will go on makin g more--she has learned the skill from Grandma Dee. For Dee, at least for the present, the answer is no. She would frame the quilts and hang them on the wall, distancing them from her present life and aspirations; to put them to everyday use would be to admit her status as a member of her old-fashio ned family. story everyday narrated woman describes herself large boned woman with rough working han ds enjoyed rugged farming life country lives small roofed house surrounded clay yard middle pasture anticipates that soon daughter maggie will married will living peacefully alone story opens women aw ait visit from older daughter husband mother sure whether they actually married always scornful fami ly life gone college seems almost distant film star mother imagines being reunited with television s how such this your life where celebrity guest confronted with humble origins maggie bright bears sev ere burn scars from house fire many years before even more intimidated glamorous sibling mother surp rise arrives wearing ankle length gold orange dress jangling golden earrings bracelets hair that sta nds straight like wool sheep greets them african salutation while companion offers muslim greeting t ries give maggie ceremonial handshake that does understand moreover says changed name wangero leewan ika kemanjo because couldn bear longer being named after people oppress friend unpronounceable name which finally reduces hakim barber muslim will pork prepared their meal whereas been scornful house possessions when younger even seeming happy when burned down delighted takes photographs including w anders asks have butter churn whittled uncle plans centerpiece table then attention captured handmad e quilts pieced grandma quilted sister known these quilts have already been promised however take in to marriage horrified appreciate these quilts says probably backward enough them everyday although i ntimidated enough surrender beloved feels sudden surge rebellion snatching from offers instead some machine stitched ones which does want turns leave parting tells really mama still live never know sp end rest evening sitting yard dipping snuff just enjoying themes meanings central theme story concer ns which individual understands present relation traditions people culture tells they understand the ir heritage because they plan priceless heirloom everyday makes clear equally confused about nature inheritance both immediate family larger black tradition matter name provides good example this conf usion evidently chosen wangero leewanika kemanjo express solidarity african ancestors reject oppress ion implied taking american names black slaves symbolic family unity after trace back time civil the se names significant because belong particular beloved individuals confusion about meaning heritage also emerges attitude toward other household items while rejects names immediate ancestors eagerly v alues their handmade goods such hand carved benches made table when could afford chairs artifacts su ch benches strictly aesthetic objects never occurs symbols oppression made things could afford them admiration seems reflect cultural trend toward valuing handmade objects rather than sincere interest heritage after offered quilt before went away college rejected fashioned style careful reading show only confused about black woman rural south although skeptical recognize limitations lives only sec ond grade education admits cannot imagine looking strange white knows bright walks sidelong shuffle although dispositions lead make best lives admire fierce pride even feel force scorn taken whole whi le clearly endorses commonsense perspective over affectations does disdain struggle move beyond limi ted world youth clearly however arrived stage self understanding sister ahead respect style techniqu e thematic richness made possible flexible perceptive voice first person narrator point view permits reader understanding both seen greater distance both young women might seem stereotypical smart rut hless college girl other sweet ineffectual homebody close scrutiny redeems characters banality examp le shyness explained terms terrible fire survived sometimes still hear flames feel arms sticking hai r smoking dress falling little papery flakes eyes seemed stretched open blazed open flames reflected ever since been like this chin chest eyes ground feet shuffle case reader learns growing high deman ds others tended drive people away friends boyfriend flew marry cheap city girl ignorant flashy turn ed faultfinding power drive better cost dearly commentary reveals scars though less visible than add ition skillful point view enriched alice walker development symbols particular contested become symb olic theme sense represent past women worked generations contain bits fabric earlier eras including scrap civil uniform worn great grandpa ezra debate over should treated used hung wall summarizes dil emma face future seen continuous ancestors answer only also making more learned skill grandma least present answer would frame hang wall distancing present aspirations would admit status member fashio nedEssay, essays, termpaper, term paper, termpapers, term papers, book reports, study, college, thes is, dessertation, test answers, free research, book research, study help, download essay, download t erm papers