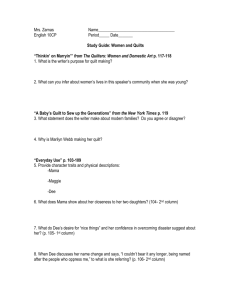

Sample Essay 2 - Survey of American Literature

advertisement

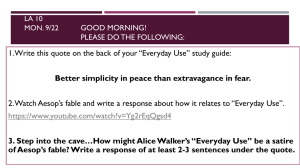

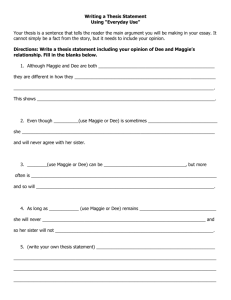

410 Writing to Interpret lit Literature _ ~ Andrews-Rice ~ ~ "'~~"",,~.;::ijii,;hW-"'Wi.': Andrews-Rice 3 2 hard churning butter, cooking over a wood-burning stove, and using the outhouse. wife to local John Thomas Dee. At this point in the story, though, Mrs. Johnson and She's darker skinned, "homely and ashamed of the bum scars down her arms and Maggie agree to go along with Dee's ways and continue to try to please her, even if legs" (47), and her simple country clothes, "pink skirt and red blouse" (49), are in they do not understand her. It is not until later in Dee's visit that they come to realize sharp contrast with Dee's fancy garb. the way Dee has embraced a heritage she does not fully understand or appreciate. To further emphasize the differences among the ways these women The fihned version of ..F. ~! w. .~",.. i ir ... n.. tho :II the story allows the viewer to understand their heritage, Walker focuses on their educations. Mrs. Johnson see Dee arrive home with her describes the way Dee would read to them before she left for college: "She washed boyfriend, Hakim-a-barber, us in a river of make-believe, burned us with a lot of knowledge we didn't both in their African clothes, necessarily need to know" (50). Even though she's somewhat puzzled by Dee's exchanging glances of knowledge, she maintains pride in her daughter, especially since Mrs. Johnson superiority and amusement as never had an education, and Maggie "knows she is not bright" and can read only they take Polaroid snapshots 411 Dee wants to capture the living conditions of her mother and sister. I hy "stumbling along good-naturedly" (50). But when Dee accuses Maggie of of the unsophisticated mother hcing "backward," Mrs. Johnson realizes how little Dee's education has taught her and sister and their shabby house, as though Dee was completely separated from nbout appreciating her heritage. such living conditions, that heritage, her family. Another way that Walker illustrates the divide between Dee's understanding.of Tbe focus on family-made quilts at the end of the story shines light on Walker's final take on how heritage is used differently by these women. Mrs. her heritage and her family's is through the use of names. When Dee arrives, she Johnson explains that Dee was offered these quilts before she left for college but announces tbat she is "Not 'Dee,' Wangero Leewanika Kemanjo!" (53). According to refused them because they were "old-fashioned, out of style" (57). Now that the the interview with Walker that accompanies the Wadsworth Original Film Series in quilts are stylish, Dee wants them in her life. She wants to hang them on her walls, Literature's filmed version of "Everyday Use," the changing of one's name to a more displaying them alongside the butter churn top that she plans to use as a "centerpiece Afrocentric name was common during this time (Everyday Use). In Dee's mind, this, on the alcove table" and dasher that she will do "something artistic" (56) with. For fashionableAfiican name is yet another way she is honoring her roots, embracing her Dee, these artifacts should be on display, not used. But for Maggie and her mother, heritage, and she tells her family that she "couldn't bear it any longer, being named thc quilts represent not only a direct link with their ancestors but a distinct form of after the people who oppress [her]" (53). Ironically, her given name carried withit a Afiican American expression, These particular quilts are made from scraps of Grandma rich inheritance, that of a long line ofDees or Dicies. Yet Dee is the daughter who Dee's dresses and from a scrap offabric from Great Grandpa Ezra's uniform "that he denies her Southern beritage and is embarrassed by her .Southern family, especially by wore in the Civil War" (56). The piecing together of these scraps to form a quilt is a Maggie, who has taken no steps to "make something of [herself]" (59) other than a testament to their importance in the heritage of this family. As Dee holds the quilts, she • 412 lit Writing to Interpret Literature 413 Andrews-Rice 5 Notes repeats "Imagine!" (57), as ifit 1 Alice is so difficult to think of'atime Walker, "Everyday when all the stitching was ~ (New York: Harcourt, done by hand, something that work will be identified Use," Tn Love & Trouble: Stories 1973) 47-59. All subsequent of Black quotations from this by page numbers. Maggie is capable of doing every day because "it was Grandma Dee and Big Dee who taught her how to quilt" I , Every time Maggie uses the quilts, she feels connected to her family. (58). When Dee' asks to take some quilts back to the city to hang on the wall; her m~ilik I;vcryday resists, saying that Maggie planned to use them. Only then does Dee reveal her Walker, Alice. In Love & Trouble: everyday-use" (57), right before she storms out of the house. At this point, when she's been denied the quilts, Dee accuses her family of you'd never know it" (59). She considers be forward looking, because of her African style and name, her education, cultural displays. In Dee's eyes, her "backward" family does not understand (59), because she knows she embraces, intimate way. lives, and understands their ;" her heritage in a vyry, and 2005. Stories of Black Women. New York: HarcoUlt, ... In lW:f! it•. Il· her every day. As Dee drives away, Maggie smiles, and it is "a real smile, not scared" Wadsworth, Luttrell, ~:.,~__...• herself to, heritage because they do not display the quilts or the butter churn, they use them Perf. Karen ffolkes, Rachel 1973.47-59. their true heritage, saying "It's really a new day for us. But from the way you and Mama.stilll.ive Use. Dir. Bruce Schwartz. Lyne OduIIlS. 2003. DVD. Thomson prejudices, accusing her sister of being "backward enough to put them [the quilts] to not understanding Works Cited .·,e _r"._". _ ... ..:.....,...,.......,.~;.r lit Andrews-Rice 1 Knitlyn Andrews-Rice Dr. Glenn Rnglish 100 7 March 2005 Honoring Heritage with Everyday Use ''Everyday Use;' one of the short stories in Alice Walkers In Love & Trouble: Stories of Black Women, vi~idly demonstrates pow three women, Mrs. Johnson and her two daughters, regard their heritage. I Through the eyes of MIs. Johnson, the story unfolds when her older daughter returns to her co~tJ.y home, mother, and sister. Throughout the story,Walker emphasizes the shared heritage of these three women and the different ways they use it. In "Everyday Use," an authentic appreciation ofheritage I docs not come from showcasing fashionable artifacts or practices; rather, it comes from embracing that heritage every day. Waiker's physical description of the sisters illustrates the different ways each pillS her heritage to use. The beautiful, sophisticated Dee embraces her heritage by showcasing the fashionable Afrocentric sentiment of the time. Her mother describes her as wearing "a dress so loud it hurts my eyes. There are yellows and oranges enougb to throw back thelight of sun," and her hair "stands straight up like the wool on a sheep" (52). But in addition to her African style, Dee also has "neatlooking" feet, "as if God himself had shaped them with a certain style" (52). That she's stylish comes as no surprise, for even before she appears in tbe story, the reader is told that "at sixteen, she had a style of her own, and knew what style was" (50). Dee is a book-smartcity woman, who uses her' knowledge of fashion and style, III enhance her physical attributes: she is "lighter than [her sister] Maggie, with nicer 409

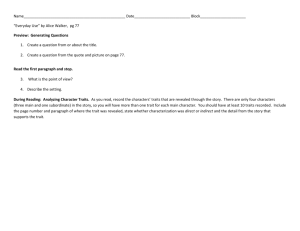

![Short_Story_Test[1].doc](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008002238_1-7a5ad2a7af6a9cd4f4b95cb6fd0a8215-300x300.png)