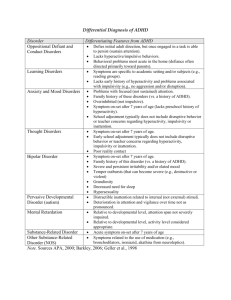

Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

advertisement