The Age of Bronze, 1876 - New Orleans Museum of Art

advertisement

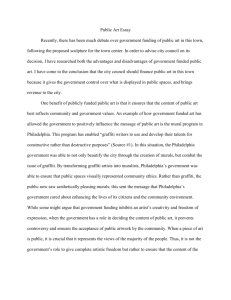

Teacher’s Manual Art and the Body New Orleans Museum of Art Introduction to the Teacher’s Manual This learning resource is intended for teachers of students in Grades 1-12 and may be adapted for specific grade levels. We hope that you will use the manual and accompanying images to help your students gain an in-depth knowledge of the collection at the New Orleans Museum of Art as part of the Art and The Body Teacher’s Workshop. Cover: Mother and Child in the Conservatory (1906) by Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1845-1927) Oil on canvas, 36 1/8” x 28 3/4” Collection of the New Orleans Museum of Art ii Art and the Body Teacher’s Manual Written by Suzanne Modica, Audio Visual Coordinator Edited by Tracy Kennan, Curator of Public Programs Kathy Alcaine, Curator of Education Allison Reid, Assistant Director for Education Written 2000; Revised 2004 This workshop and its accompanying materials were underwritten by The RosaMary Foundation iii iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: The Body in Art 1 The Age of Bronze, 1876 2 Madonna and Child with Saints, c. 1340 5 Mother and Child in the Conservatory, 1906 7 Pair of Female Ere Ibeji, Early 20th Century 9 Mother and Child, 1983 11 Bather, 1916-1917 12 Woman in an Armchair, 1960 14 Buddha, 19th Century 15 Image List 17 Vocabulary 29 Timeline 32 Curriculum Objectives 38 Bibliography 40 v vi Introduction: The Body in Art Although humanity is very diverse--we may have different color skin, be of opposite genders, speak various languages or follow unique customs--the one common denominator is the human body itself. The human form is the one universal among all the things that make us individuals. Perhaps one reason why artists from the prehistoric era to the present have been fascinated with the human body is that in using it, the viewer and the artist share common ground, allowing the viewer to relate to or to understand that which is depicted. Through the body, an artist is able to communicate a number of things from simple actions and events to more complex concepts and emotions. Furthermore, it may also provide insight into the mores and values that are characteristic of the age in which the artist lived. Finally, the human body, depicted for its sheer beauty, may convey the artist’s or that particular society’s sense of aesthetics. Through the following artists, who all share an interest in the body, we can see just how individuals from different times and various traditions treat bodily representations and how they may differ from our own culture. The Age of Bronze, 1876 August Rodin, the master sculptor of the Post-Impressionist period, saw himself as heir to the nude sculptural tradition that was transmitted from the ancient Greek world to the Renaissance. In the last few decades of the nineteenth century, the art world was turned on its head as artists began to reject the classical models of the French Academy, seeing the art as uninspiring and tired. Leading rebellious groups such as the Impressionists and the Post-Impressionists experimented with light, line and color as a means of expression. Rodin himself rejected the traditional sculptural styles of the day claiming, “My liberation from academicism was via Michelangelo.”1 Although the basic body type in Rodin’s artwork descends from Greek models, he infused them with new life by incorporating the expressive power of Michelangelo’s nonfinito sculptures. The ancient Greek civilization, revered by Renaissance masters and French academic painters, was one of reason. Philosophers such as Socrates (c. 470-399 BCE) and Plato (c. 429-347 BCE) believed that one might discover truth and beauty through rational thought. This notion carried over into art and architecture where artists sought a mathematical model that would reveal physical perfection through the traits of symmetry, balance, harmony and order. The most enduring model of the Greek ideal is Polykleitos’s Doryphoros (Image 1), or Spear Bearer. The statue, completed at the height of the classical period in Greece, circa 450 BCE, is no longer extant, but exists in copies made by the Romans. Doryphoros was nicknamed “The Canon,” both as a reflection of the rules set down by the renowned artist Polykleitos in his treatise on the human body and because of the sculpture’s reign as the measuring stick for ideal beauty. Canon, which means both “rule” and “measure” in Greek, is also an appropriate moniker as Polykleitos developed a series of proportions based upon a unit (some believe it to be the length of the statue’s index finger) that was then used to generate the measurements for the rest of the body. With Doryphoros, Polykleitos effectively created a mathematical equation for perfection. Doryphoros depicts a nude male athlete who seems to pause in mid-step. The naturalism of the work stems from the figure’s balancing primarily on one leg, called contrapposto. Here, most of Doryphoros’s weight is placed over his right foot as his left heel is raised giving the impression of mobility. His left hand, originally holding a spear, swings up while his torso 1 2 Riopelle, p. 35. tilts slightly in the same direction, effectively balancing the figure’s weight. Polykleitos modeled the figure, emphasizing and defining the arm muscles as well as his pectoral and abdominal muscles. Although the figure is rendered naturalistically, Doryphoros is also highly idealized: his facial features, as well as his body construction, are all very regular, symmetrical and balanced and in this regard the statue was the epitome of Greek thought and beauty. Over 2000 years later, August Rodin would find the proportions and beauty of Doryphoros still dominant. Rodin, born in 1840, entered an art world that stressed formal or academic training based upon classical theory and images. Although Rodin showed some skill, entering the Imperial School of Drawing and Mathematics in 1854, he was denied entrance three times to the École des Beaux-Arts, the major artistic training institution. Following his last failed attempt in 1857, Rodin entered the workshop of the famed artist Albert Carrier de Belleuse where he mastered the decorative sculptural style for which CarrierBelleuse was renowned. The two were forced to leave for Belgium in 1870 when France lost the Franco-Prussian War and the resulting Commune closed the sculpture yards. While in Belgium, Rodin parted ways with Carrier-Belleuse, choosing to concentrate on his own work. In 1876, he began work on an almost life-size sculpture of a man awakening to a new consciousness called Age of Bronze (Image 2). Frustrated after a few disappointing attempts, Rodin took leave of the sculpture and went on a tour of Rome, Pisa and Florence to study Renaissance masters. It was at the Accademia in Florence that Rodin found the inspiration for his unfinished sculpture: he based the enigmatic pose of Age of Bronze on Michelangelo’s heroic The Dying Captive (1514-1516) (Image 3) that was on loan from the Louvre. Rodin returned to Belgium and renewed work on Age of Bronze. Wanting to avoid the conventional poses of professional models, he hired a Belgian soldier to pose for the figure. Rodin believed that only the spontaneous, and therefore “true” movements of the model should be represented. Any attempt at imposing characteristics upon the sculpture would destroy the harmony of the piece, leading to ugliness. Like the Greek artists, Rodin thought that truth in expression equaled beauty: “That which is ugly in art is that which is false and artificial--that which aims at being pretty or beautiful instead of being expressive.”2 Like Doryphoros, Rodin’s finished sculpture originally carried a spear, but Rodin removed the tool, opting for a more ambiguous subject matter which was emphasized by the vagueness of the title. Such simple changes, though, were quite revolutionary. Artistic standards of the day dictated certain figural types for a given subject matter--but Age of Bronze had no 2 3 Rodin, unpaginated. apparent subject matter! And the title, which had been changed from The Vanquished, did not clarify matters. The work caused an even greater scandal at the Salon where jurors thought the figure to be so life-like that they refused to believe that Rodin actually sculpted the image. They accused him of making a mold or cast of the model, a common practice of the day. The controversy was only quelled after numerous friends and artists vouched for Rodin’s carving skills. Age of Bronze was based upon Michelangelo’s The Dying Captive, which in turn was derived from classical sculpture such as Doryphoros. But more than simply its pose, Rodin was inspired by Michelangelo’s skill at emphasizing musculature and the tension that existed within his Captive series as the subjects seemingly struggled to break free of the marble. The unfinished character of The Dying Captive also appealed to Rodin as something that was contrary to the polished academic works that were being produced at the time. Unlike Doryphoros which is smooth and idealized suggesting that which is timeless, Age of Bronze still has a bit of Michelangelo’s nonfinito quality reflecting the momentary and the tension as the boundaries of body meet the surface of the sculpture. Although the pose, the weight shift, the proportions and the serene expression of Age of Bronze are similar to those of Doryphoros, the attention to the surfaces and musculature of the unidealized figure were not at all in accordance with academic standards. 4 Madonna and Child with Saints, c. 1340 The polyptych, Madonna and Child with Saints (c. 1340) (Image 4), was painted in Italy during the Gothic period by a follower of Bernardo Daddi. The work shares the characteristics of two very different artistic worlds and traditions--the Byzantine Empire and the Italian Renaissance. The Medieval era (c. 800-1350), of which the Gothic period was just one phase, was called the “dark ages” by Renaissance scholars to distinguish it from the rational and the naturalistic tendencies of the classical world of the Greeks and Romans and of the Renaissance. Rather than attempting to recreate the exact physical appearance of objects and of people, Byzantine artists sought to promote Christian beliefs and express religious meaning through standardized images that stood against flat, golden backgrounds representing the timeless and immortal realm of Heaven. The Byzantine Empire, whose capital was Constantinople (modern day Istanbul, Turkey) was the center of the new Christian faith. In 313 Constantine the Great issued the Edict of Milan calling for the toleration of all religions, including Christianity, which had been persecuted by the Romans. In Constantinople, royal patronage from Constantine and subsequent emperors allowed Christianity to flourish. And, as it prospered, a standardized style evolved that made the Christian religious figures easily identifiable. The rulers of the Byzantine Empire were deemed semi-divine, occupying a spiritual position under God yet above their own subjects, and therefore were also represented in a standardized fashion. The mosaic, Empress Theodora and Her Attendants (c. 547) (Image 5), from the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, is a good example of the Byzantine figurative tradition--one that inspired the follower of Bernardo Daddi 800 years later. The central figure Empress Theodora, whose husband Justinian I ruled the Byzantine Empire at the height of its power, is depicted flanked by a number of priests and assistants. Her body, slightly overlapping the other figures, 5 underscores her superior stature. The artist places the figures against a gold background--a device that made the images appear to float and shimmer under candlelight--reinforcing the spiritual or heightened status of the figures. The Empress and attendants seem flat or two dimensional primarily because of the way in which the artist has depicted their drapery. The figures’ clothing is rendered geometrically with abstract patterns: the folds are simplified into lines and angles providing little sense of the shape of the body underneath it. We are only aware that the figures are somewhat elongated and their features are rather delicate. At this time women and lesser figures were not individualized in art. Rather the Empress and her attendants share the same facial features: an oval head, a long straight nose, almond-shaped eyes and a small mouth. These conventions--the gold background, the standardization of the figures’ countenance and their flat appearance--is not meant to copy the human form exactly, but to express the figures’ heightened spirituality and to separate them from the earthly and the mortal world. For many years Constantinople was under the power of Moslem forces until the Crusaders recaptured the city in 1204. For the first time in years the Byzantine mosaics could be seen, leading to a flood of artistic inspiration for Italian artists, including the follower of Bernardo Daddi. He, too, has positioned the Madonna and Christ Child against a golden screen to emphasize their heavenly nature. The central figures are flanked on the left by St. John Gualbert and St. Pancras and on the right by St. Michael and St. Benedict. The saints are depicted slightly smaller than the Virgin Mary, signifying that they are of lesser importance. Like the mosaic of Empress Theodora and Her Attendants, the figures in New Orleans Museum of Art’s polyptych are set within a shallow space, but the artist, rather than flattening the figures with angular drapery, has attempted a degree of naturalistic representation. The features of Madonna, the Christ Child and saints, especially the eyes, share a similarity, but their bodies have a greater mass which is accentuated by two elements. One, the folds of the drapery are less schematized-they curve softly and reflect the shape of the bodies underneath. Two, the artist has used light and shadow to define the forms--he has modeled the figures. The Renaissance artist’s attention to the body and the way light defines the body’s musculature set them apart from the flattened and angular forms of the Byzantine world which were mistakenly perceived as ignorant and unskilled. 6 Mother and Child in the Conservatory, 1906 Though Mother and Child in the Conservatory (1906) (Image 6) by Mary Cassatt is not meant to be a religious work like Mother and Child with Saints, its subject matter celebrates the strong bond between a mother and her offspring. While more naturalistically rendered than the previous polyptych, Mary Cassatt diverged from the accepted standards of the day, as dictated by the French Academy, which were based upon strict adherence to classical models of the human form. Mary Stevenson Cassatt was born May 22, 1844 into an affluent Pennsylvania family but spent much of her formative years with her parents and siblings abroad in Paris, Heidelberg and Darmstadt. After the death of her eldest brother, the Cassatt family returned to Pennsylvania and settled in Philadelphia. There Cassatt studied painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and eventually chose to further her artistic education in France. Cassatt experienced some early success as two of her paintings were accepted by the Paris Salon. Even with this encouragement, she vowed never again to send another work to the Salon when she realized that another of her pieces with a lighter palette was not acceptable to the standards of the jury because it was seen as less than serious. The lighter palette was inspired by an exhibition of independent artists in 1874 and 1876 where Cassatt saw works by Claude Monet, Edgar Degas and Edouard Manet among others. This group of artists, noted for their interest in the changing qualities of light, the natural landscape and studies of Parisian life, was pejoratively coined the Impressionists by Louis Leroy. Cassatt and Degas were later introduced by a mutual friend. When Degas saw her work he exclaimed: “That is genuine. There is someone who feels as I do.” 3 He later invited Cassatt to exhibit with the Impressionists. Cassatt remarked, “I accepted with joy. Now I could work with absolute independence without considering the opinion of a jury. I had already recognized who were my true masters. I admired Manet, Courbet and Degas. I took leave of conventional art. I began to live.”4 This statement is indicative of Cassatt’s desire to move beyond pure replication of the human form and to paint subject matter that was familiar to her in a manner that diverged from the academic and accepted style. 3 4 7 Bullard, p. 13. Bullard, p. 13. Unlike the rest of the Impressionists, Degas was more interested in the way the human body was shaped and how it moved rather than in the effects of light, and Cassatt followed him in this regard. While Degas painted subjects from the cafés, bars and laundromats, these places were not considered appropriate venues for an upper-middle-class woman to visit. Rather, Cassatt was limited by her stature and her gender to paint scenes at the opera or scenes of domestic life. It is no wonder then, that images of the home and specifically, of mothers and children, dominate her oeuvre. This later work, Mother and Child in the Conservatory, is representative of Cassatt’s interest in the domestic sphere and the human body. It also highlights her talent at capturing a fleeting moment and making it represent the universal bond between a mother and her child. Although the figures’ proportions are derived from the classical canon, they do not share the idealization and the precise line that is characteristic of either the academic art of this period or of the Renaissance. Rather, the bodies seem soft or undefined as the musculature is not apparent. Cassatt achieves this effect, not by totally abandoning modeling, but by employing a longer brushstroke and a thicker application of paint. She also uses white highlights to suggest sunlight as it plays across the rounded forms of the sitters, especially the mother’s gown, in order to reinforce the sense of a captured tender moment. Although the child gazes out at the viewer, the mother tilts her head towards her child and their interlocking hands. The mother’s absorption in her child attests to their intimacy and projects some sort of real psychology. The “genuine” quality that Degas commented upon is even more amazing when one considers that most of Cassatt’s mother and child pairs were merely models and not at all related to each other. 8 Pair of Female Ere Ibeji, early 20th century The Yoruba-speaking people come from regions in Nigeria and the Popular Republic of Benin. Their society, over a millennium old, first rose to power in 800 in the sacred city of Ife. An artistic tradition can be traced back to about the year 1100 when they perfected the technique of sculpture in both terracotta and stone and later in bronze. The Yoruba cultures prospered until the arrival of European ships in the fifteenth century after which time the kingdoms began to decline due to warfare and the slave trade. However, colonization and the diffusion of Yoruba peoples to the Americas may have aided in the dissemination of the African artistic tradition, ultimately causing a transformation in Western art in the twentieth century. The Yoruba believe in the existence of two realms: the world of the living, or the aye, and the spirit world, called the orun which is the domain of ancestors, gods and spirits. The belief in the transience of the mortal realm is highlighted in the Yoruba saying: “Aye l’ajo, orun n’ile” or “The world is a journey, the otherworld is home.”5 In an area in which life can be so short (in some places up to half of all infants die before they reach the age of five), the afterworld is a promise of eternal life. The Yoruba have the highest incidence of twin births in the world--for every thousand births, close to forty-five are twins. In a society in which children represent the lineage of the family and are providors of food and labor for aging parents, twins are especially revered as emi alagbara, or powerful spirits, who have the ability to bring abundance to their family. In the event that one or both twins die, no matter the age, the parents consult a diviner, who in turn 5 9 Wardwell, p. 15-16. directs them to a carver who carves an ere ibeji (Image 7), or an image of the deceased. In order to invoke the deceased’s emi, or spirit, the artist places a sacrifice for it at the base of an ere ona tree, used to carve the image, then submerges the finished figure in a mixture of water and leaves. On the day the parents are to receive the figure, they prepare a feast celebrating the carver. After making a sacrifice to the god Ogun and after offering a prayer to the ibeji or twin figure, the mother wraps the carving as she would a living child then returns home singing to and dancing with it. Once the ibeji is home, the mother lavishes care upon the figure as if it were a real child-she may decorate it with waist or neck beads, cowrie shells or gold rings. Food is also prepared for the ibeji on special occasions or during rituals. The Yoruba believe that a child’s spirit, represented by the ibeji, lives on in the orun and again, care lavished upon the memorial figure will result in prosperity for the still-living family members. Thus, the singing to, dancing with, feeding and decorating of the ibeji figures transform the carving from merely a memorial object into something that actually houses the spirit of the deceased. Because the mothers treat the ibeji as a real child, one might assume that the carvings are naturalistic. Rather they are the embodiment of the spirit of the twin and symbolically represent the fullness of life. The figures stand erect, although their stout legs are slightly bent. The breasts of the ibeji are emphasized, perhaps as an act of supplication or as a symbol of the fertility and abundance their family desires. Although ibeji may differ depending upon the carver, they tend to be sturdy and strong. Rather than the western world’s emphasis on the definition of musculature, the limbs of these carvings are often tubular stressing the figures’ balance. It is their strength and solidity that reminds us that they live on in the orun. The heads of the ibeji are oversized for their bodies corresponding to the belief that it is within this area that one’s own fate resides. The serene faces bear large, almond eyes and like a window to the soul, they are indicators of the ibeji’s inner strength and inner life force. These figures were carved by the master Olowe of Ise (died 1938) who only accepted royal commissions. This clue in addition to the lineage markings on their faces may indicate that these twins were members of the king’s family. 10 Mother and Child, 1983 Elizabeth Catlett’s Mother and Child (Image 8) combines the figurative tradition and the mother and child motif of western artists with the simplicity and solidity found in the Yoruba ere ibeji carvings. Catlett’s forms are a reflection of the strength and nurturance that she inherited both from her family and from her commitment to friends and the working-class people she met in Harlem and in Mexico. Although her African-American heritage was a factor in her being denied entrance to the Carnegie Institute of Technology, Catlett (born 1919) was firmly rooted in a scholarly and artistic tradition. Her father, who died when Catlett was young, was a respected mathematics professor at Tuskegee Institute, the same place where Booker T. Washington and George Carver taught. She continued her education at Howard University and then in 1940 earned a Master of Fine Art at the University of Iowa where she studied sculpture under Grant Wood, a regionalist painter best known for his work, American Gothic. After graduation Catlett accepted a position at Dillard University in New Orleans where she eventually became the head of the art department. In the 1940s Catlett moved to New York where she immersed herself in the environment of the post Harlem Renaissance. She surrounded herself with talented artists like writer Langston Hughes and the painter Jacob Lawrence. While in New York, she received the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship allowing her to create a series of works on black women, but her many obligations in the city, including the sculpture classes she taught at the Carver School in Harlem, did not enable her to concentrate on her own work. In order to dedicate herself to her own art, Catlett made the decision to leave for Mexico where she worked at the Taller de Gráfica Popular, a workshop that sought to make art more accessible to the working-class population. It was in Mexico during the late 1940s and 50s that Catlett began to experiment with the medium of wood. Like Cassatt’s Mother and Child in the Conservatory, Catlett’s composition represents maternal bonds. But while Cassatt’s work accomplishes this by evoking a quiet, though familiar moment through a series of glances and touches, Catlett creates the same sensibility through gently curving masses and the solidity of her wooden medium. Catlett is recorded as saying, “I try to use form as expression. For example, people associate certain things with certain kinds of lines and certain kinds of shapes. So I try to use form symbolically in order to express different ideas.”6 The rounded forms of Cassatt’s work are further simplified in Catlett’s Mother and Child. She has reduced the bodies to planar expanses: the limbs of the figures and the woman’s face are defined only by the ridges that form where the planes merge. The bodies are not modeled as they are in Mother and Child in the Conservatory and in Madonna and Child with Saints and the drapery does not suggest the shape of the form underneath of it. Rather, contours are suggested through the grain of the wood as it curves and the clothing of the woman cannot be distinguished from her own skin. Catlett’s belief that art should be accessible and 6 Lewis, p. 85. 11 comprehendable to all classes, regardless of education results in the reduction of detail in the sculpture, making the pair a universal symbol of maternal nurturing and love. 12 Bather, 1916-1917 Jacques Lipchitz, born in Lithuania in 1891, was the son of a successful Jewish contractor. Neither his father nor the czarist regime allowed him to take lessons at the St. Petersburg Academy, so with the help of his mother and his uncle, Lipchitz planned a secret trip to France. Lipchitz had little artistic training in Russia--only a few classes in Bialystok and Vilna--but he entered a Paris that was brimming with artistic talent, both native and foreign. Among others, Lipchitz befriended Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani and the sculptor Constantin Brancusi. In 1913 Lipchitz met Pablo Picasso, who along with Georges Braque was one of the founders of Cubism, a movement beginning in 1908 that had great impact on the art world in both painting and sculpture. Picasso and Braque attempted to revise the Renaissance model of precisely imitating physical form and space. In this model, space mimics reality almost as if the picture is a window through which the viewer looks. The Cubists however took perspective and the human body and fractured them into facets. The image was then reassembled using the technique of passage in which the facets fuse into one another making objects in the foreground appear at the same depth of objects in the background--it is as if the viewer can observe an object from multiple angles simultaneously. In Picasso’s work David-Henry Kahnweilier (1910) (Image 9), Picasso dissolves the sitter’s body to a point that it becomes one with the background. The face and the hands, the most recognizable features of Kahnweiler, appear as if disassembled and then reattached. The recombination of body parts is apparent in Kahnweiler’s face which has been reduced to a series of intersecting facets. The merging of light and shadow, which in Renaissance art had produced modeling and a three-dimensional quality, is still apparent in the Cubist work. However, in this case the shadow is not unified and light appears to be shining on the figure from various spots--again lending to the impression that the figure is presented from multiple angles simultaneously. During the early 1900s before Cubism, Rodin’s work dominated the world of sculpture. Picasso and Lipchitz were at the forefront in developing sculpture that was grounded in the rules of Cubism in which a fractured space or subject is integrated into the work. Beginning in 1917 Lipchitz began to focus on easily recognizable archetypes--the bather or the musician--that allowed the artist to experiment with Cubist theories while retaining the universal associations and recognizability of the figurative tradition. Here, Bather (Image 10), is reduced to a series of vertical and horizontal planes punctuated by countercurves. The only truly recognizable part of the body is the belly button indicating that the figure is nude. Traditionally, a sculpture is three dimensional, allowing the viewer to walk around it and see the object from different vantage points. But because the surfaces of the bather’s body have been rearranged, this sculpture, like 13 Cubist paintings, allows the viewer to see the object from multiple perspectives--from a single point. Bather, although greatly simplified, shares the pose of Rodin’s Age of Bronze--one of the arms seems to be raised behind the head and the figure seems to balance on one leg. However, all traces of the Renaissance body type are gone and the figure appears planar and substantial. 14 Woman in an Armchair, 1960 Pablo Picasso’s Woman in an Armchair (1960) (Image 11) was completed long after the artist’s Cubist phase. During the fifty years that elapsed between the Cubist phase beginning in 1908 and the completion of NOMA’s work, the Spaniard’s work changed frequently. In Woman in an Armchair Picasso revisits the Cubist’s style of fracturing the bodily form, but now the sharp facets and the element of passage have been replaced by organic curves. Although his Cubist phase sought to reinvent the Renaissance model of space, leading him towards almost total abstraction, Picasso’s art has always been rooted in a figurative tradition, especially with the woman as his subject matter. Here, Picasso has painted his second wife, Jacqueline Roque, seated in an armchair--a motif he explored during the 1930s. Jacqueline’s form is defined by a thick black outline rather than by traditional modeling. Although Jacqueline’s body is fairly flattened and she appears to dissolve into the armchair, Picasso does give her some weight by using patches of gray paint to emphasize the rounded shape of her breast. The long brushstrokes give the impression of a painting rapidly executed--for instance, the sitter’s hands are reduced to painterly slashes and only suggest a real hand while her crossed legs are represented by a single slashing line. Woman in an Armchair returns to the Cubist manner of indicating simultaneous multiple views of an object. Here, Jacqueline is depicted both frontally and in profile, views that are differentiated simply through the neutral colors of black and white. Jacqueline’s face is the most defining feature of the painting with attention paid to her large eyes and long mane of black hair. Picasso’s work, although simple on the surface, is made more complex through the contrasting forces of the two dimensional in opposition to the three dimensional. The painter accomplishes this by painting black against white, merging profile views with frontal views and contrasting a slashing application of paint with the rounded contours of the human body. 15 Buddha, 19th century Buddhism was founded by Siddhartha Gautama (born 563 BCE) in India where it remained until Indian monks introduced the religion to the Chinese in the first century. From there it spread to other Asian countries such as Japan where it became a principle factor in the arts. Gautama was born a prince whose father shielded him from the poverty and the misery of the world beyond the palace gates. On a rare occasion in which the prince had contact with the outside world, he was confronted in succession by three figures: a person stricken with illness, an aging man and a corpse. It was at this moment that Gautama realized that sickness and death are inevitable fates, and in response he renounced all his worldly possessions and his royal position and left the palace in an effort to discover the true meaning of human existence. After years of meditation and asceticism, Gautama reflected under a bodhi tree and achieved enlightenment, or an understanding of human reality, and became Shakyamuni Buddha or Shaka, the historical Buddha. The Buddha taught that everything in this world, every moment is dependent on the next and our actions force us into a cycle of reincarnation. Only by attaining enlightenment can we transcend this cycle and enter nirvana. According to the Buddha, the first step is to recognize the Four Noble Truths. One, life is suffering. Two, desire and ignorance are the reason for our suffering. Three, we can only free ourselves from suffering by eliminating these evils. Finally, to achieve liberation we must follow a middle course that lies between indulgence and asceticism called the Eightfold Path. The Eightfold Path is a sort of code to live by that calls for right understanding, right speech, right purpose, right conduct, 16 right livelihood, right effort, right awareness and right concentration. If one acknowledges the Four Noble Truths and follows the Eightfold Path they may eventually reach nirvana and stop the cycle of reincarnation. The image of the Buddha from Japan (Image 12), like the gods of other religions, became standardized over time, leading to greater recognizability amongst the religion’s followers. In the case of the Buddha, there are 32 attributes or shogo that allow us to identify the figure as a Buddha. One of these attributes is the ushnisha or nikkei, a cranial protuberance above the head. Another shogo is the Buddha’s hair that is defined by small snail shell curls. It is believed that when Siddhartha Gautama left home, he removed his turban and shaved his head whereupon the stubble tightly curled. The Buddha also exhibits a round tuft of hair between his eyes, called an urna or byakugo, which is a third eye representing his all-seeing nature. His true eyes are nearly closed slits representing the peace and enlightenment he has attained. No decorations are worn beside a modest tunic because the Buddha has given up material wealth, but his earlobes, elongated from the heavy earrings he wore as a prince, indicate that he is a great source of wisdom. The Buddha’s ample, rounded body, perhaps a reference to his earthly presence, sits in a position of meditation upon a lotus flower, a symbol of purity. Finally, the Buddha exhibits a set of mudra, or hand signals. His right hand indicates the mudra of vitarka or that of argument in which his thumb and forefinger form a circle and the rest of the fingers remain extended. His left hand performs the mudra of varada or grace and charity where the fingers are extended with the palm facing skyward.7 7 Gupte, p. 9. 17 Image List Image 1: Doryphoros (Spear Bearer) (c. 450-440 BCE) by Polykleitos Roman copy after the original bronze Marble, 6’ 6” 18 Image 2: Age of Bronze (1876) by August Rodin (1840-1917) Bronze, 72” Collection of the New Orleans Museum of Art 19 Image 3: The Dying Captive (1514-1516) by Michelangelo Buonarotti (1475-1564) Marble, no dimensions Louvre, Paris 20 Image 4: Madonna and Child with Saints (c. 1340) by a follower of Bernardo Daddi Tempera and gold leaf on linden wood, 50 5/8” x 101 3/4” Collection of the New Orleans Museum of Art Image 5: Empress Theodora and Her Attendants (c. 547) Church of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy Mosaic, 8’ 8” x 12” 21 Image 6: Mother and Child in the Conservatory (1906) by Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1845-1927) Oil on canvas, 36 1/8” x 28 3/4” Collection of the New Orleans Museum of Art 22 Image 7: Pair of Female Ere Ibeji (early 20th century) by Olowe of Ise (died 1938) Wood, brass tacks and glass beads, 13 1/4” Collection of the New Orleans Museum of Art 23 Image 8: Mother and Child (1983) by Elizabeth Catlett (born 1919) Mahogany, 53” x 13” x 13” Collection of the New Orleans Museum of Art 24 Image 9: David-Henry Kahnweiler (1910) by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) Oil on canvas, 39 5/8” x 25 5/8” The Art Institute of Chicago 25 Image 10: Bather (1916-1917) by Jacques Lipchitz (1891-1973) Bronze with gold patina, 27” Collection of the New Orleans Museum of Art 26 Image 11: Woman in an Armchair (1960) by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) Oil on canvas, 45 1/2” x 34 3/4” Collection of the New Orleans Museum of Art 27 Image 12: Buddha (19th century) from Japan Gilt wood, 63” Collection of New Orleans Museum of Art 28 29 Vocabulary Archetype: A type or a perfectly typical example after which others are modeled. Asceticism: The practice of renouncing the comforts of society and leading a life of austerity and selfdiscipline. Aye: The mortal realm or the world of the living for the Yoruba peoples. Byakugo: The Japanese word for urna. In Buddhist art, it is the tuft of hair on the forehead that is a characteristic mark of a Buddha and a symbol of divine wisdom. Byzantine Empire: The eastern part of the late Roman Empire founded by Constantine the Great in 330. The Byzantine Empire, whose capital was Constantinople, was ruled by Constantine’s successors until the 1450s. Canon: Greek for “rule” or “measure.” It refers to a set of bodily proportions described by the Greek artist Polykleitos that were meant as a mathematical equation for physical perfection. It is also the nickname for Polykleitos’s sculpture, Doryphoros, who exhibits this particular set of measurements. Contrapposto: Literally meaning “around the post,” it is a way of depicting the human body in which its weight appears to be shifted onto one leg. Contrapposto first appeared in sculpture from ancient Greece. Cubism: A movement founded in 1908 by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in which objects are not presented in illusionistic depth but are depicted as parallel to the picture plane. The three-dimensional subject is fractured, making it appear as if it were disassembled and then put back together. Diviner: A person who foretells future events or discovers hidden knowledge of a supernatural nature. Eightfold Path: A Buddhist code to live by calling for right understanding, right purpose, right speech, right conduct, right livelihood, right effort, right awareness and right concentration. Emi: A spirit in the Yoruba culture. Emi alagbara: A powerful spirit in the Yoruba culture. Enlightenment: The achievement of truth and spiritual understanding. In Buddhism, enlightenment refers to the understanding of human existence and human suffering. Ere ibeji: For the Yoruba peoples it is an image or a memorial figure of a deceased twin. Facets: The shards or fragments that result from a Cubist subject being taken apart and reassembled. Four Noble Truths: To achieve enlightenment, one must understand four things. One, life is suffering. Two, desire and ignorance are the reasons for our torment. Three, when one removes desire and ignorance from existence, one will stop suffering. Four, the Middle Way, a happy medium between asceticism and indulgence is the path to liberation. French Academy: Also known as the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, it was founded in 1648 under Louis XIV and his chief minister, Cardinal Richelieu. The French Academy promoted the learning 30 of classical art through the copying of Greek and Roman sculpture and maintained strict control over its members’ art. Gothic period: Giorgio Vasari, an Italian Renaissance art historian, coined the term in the sixteenth century to refer to an architectural and artistic style prevalent in western Europe from 1150 to 1400. Although there were regional variations, in architecture the Gothic style is characterized by elegant, soaring interiors. In sculpture and painting, the Gothic style is reflected in elegant, elongated forms that were meant to evoke an emotional response from the viewer. Italian Renaissance: A period of learning and creativity in Italy, beginning in 1400 and ending in about 1575, which looked to the ancient Greek and Roman artistic and philosophical traditions for inspiration. Renaissance artists sought to perfect the illusion of physical reality through the depiction of idealized figures placed within a rationally defined space. Louvre: Known as the Musée de Louvre, it opened in Paris, France in 1793 allowing public access to the royal art collection. Modeling: In painting, the process of creating the illusion of three-dimensionality on a two-dimensional surface by the use of light and shade. In sculpture, modeling is the process of molding a threedimensional form out of a malleable substance. Mosaic: Images formed by small colored stones or glass pieces (called tesserae), affixed to a hard, stable surface. Mudra: A symbolic hand gesture in Buddhist art. The many hand gestures denote certain behaviors, actions, feelings or ideas. Nikkei: The Japanese term for ushnisha. In Buddhist art, a round turban or bun that symbolizes enlightenment. Nirvana: In the Buddhist religion, nirvana refers to the state of absolute freedom from the pain and care of the external world one reaches when they are freed from the cycle of reincarnation. Nonfinito: In Renaissance sculpture it is the rough or unfinished state. Oeuvre: An artist’s body of work or portfolio. Orun: For the Yoruba peoples it is the spirit world which is the realm of ancestors, gods and spirits. Painterly: A style of painting that emphasizes the surface effects and techniques of brushwork. Passage: Refers to the Cubist technique of blending adjacent shapes so there is little differentiation between fore, middle and background. Perspective: A method of representing three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. Using mathematical models and modulations in color or in the size of objects, artists can create the sense of depth, making the painting appear to be an extension of the viewer’s own real space. Polyptych: An altarpiece constructed from multiple panels. 31 Post-Impressionism: A period following the Impressionist painters, from 1880 to 1910. It does not refer to a collective style but a time period in which principal artists Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Cézanne, Georges Seurat, Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh worked and developed distinctly different styles. Salon: The annual display of art by artists in Paris during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It was originally established to show the artworks by members of the French Academy. Shaka: The Japanese name for Shakyamuni Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama), the first historical Buddha. Shakyamuni Buddha: The name given to Siddhartha Gautama after he achieved enlightenment, identifying him as the first historical Buddha. Shogo: Japanese for “attributes” or “characteristics.” Traditionally, the Buddha is represented by 32 characteristics that allow him to be identified. Ushnisha: In Buddhist art, a round turban or bun symbolizing enlightenment. Urna: In Buddhist art, the tuft of hair on the forehead that is a characteristic mark of a Buddha symbolizing divine wisdom. Varada: This mudra, or hand gesture, represents grace. The palm of the hand with fingers extended downward, is held below the waist. Vitarka: This mudra, or hand gesture, represents argument. The thumb and the index finger are joined to make a ring. All other fingers are extended upwards. 32 Timeline c. 1100 BCE: The Zhou dynasty begins after the Shang rulers are defeated in China. 776 BCE: The first Olympic Games in Greece are held. 563 BCE: Siddhartha Gautama, or Shakyamuni Buddha is born in central India. 770 BCE: The beginning of the Spring and Autumn period in China in which ten states emerge as powers. 551 BCE: Confucius is born in China in the state of Lu. 509 BCE: Lucius Junius Brutus becomes the founder and first consul of the Roman Republic. 483 BCE: Shakyamuni Buddha dies. 479 BCE: Confucius dies. c. 470 BCE: Socrates is born. 464 BCE: Artaxerxes I begins his rule of Persia. c. 450 BCE: The High Classical period in Greece. The artist Polykleitos sculpts Doryphoros, or Spear Bearer. 438 BCE: The Parthenon in Greece is built by Kallikrates and Iktinos. c. 429 BCE: Plato is born. 347 BCE: Plato dies. c. 400: The Olmec civilization in Mesoamerica ends. 46 BCE: Julius Caesar ascends power in the Roman Republic. 72: The Colosseum in Rome is begun. 125: The Pantheon is built in Rome. 220: The Han Dynasty in China collapses. 313: Constantine the Great issues the Edict of Milan calling for religious tolerance. For the first time Christianity is an accepted religion. 330: Constantinople is made the new capital of the Roman Empire. 386: The Northern Wei dynasty begins in China. 527: Justinian I and his wife Theodora become rulers of the Byzantine Empire. c. 547: The mosiac, Empress Theodora and Her Attendants, is installed at the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. c. 570: Muhammad is born in Mecca. 632: Muhammad dies in Medina. 33 800: The Yoruba civilization is established in the sacred city of Ife in Benin. 800: Charlemagne is granted the title of emperor. c. 870: The Vikings settle Iceland. 1066: William the Conqueror invades England. 1100: The Yoruba peoples perfect the technique of sculpture. c. 1150: The Gothic period begins. 1174: The Leaning Tower of Pisa is begun in Italy. 1204: Christian forces reclaim Constantinople from the Moslems. 1215: King John signs the Magna Carta at Runnymede, England. 1337: The Hundred Years’ War between France and England begins. c. 1340: A follower of Bernardo Daddi paints the polyptych, Madonna and Child with Saints. 1348: The Black Death or the Bubonic Plague sweeps Europe. 1350: The Leaning Tower of Pisa is completed. 1368: The Ming Dynasty begins in China. c. 1400: The Gothic period comes to an end just as the Renaissance begins. 1429: Joan of Arc leads the French army in the Battle of Orleans. 1452: Leonardo da Vinci is born in Vinci, Italy. 1453: The Byzantine Empire ends when Constantinople falls to the Turks. 1475: Michelangelo Buonarroti is born in Caprese, Italy. 1501: Michelangelo sculpts David for the city of Florence, Italy. 1508: Michelangelo begins work on the Sistine Ceiling in Rome. 1453: The Hundred Years’ War ends. 1483: Martin Luther is born in Germany. 1503: Leonardo da Vinci begins the Mona Lisa in Italy. 1509: Henry VIII comes to power in England and marries his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. 1513: Ponce de Leon discovers Florida and claims it for Spain. 1514-16: Michelangelo sculpts The Dying Captive. 1517: Martin Luther posts his 95 Theses on the door of a Wittenberg church calling for the reformation of the Christian church. 1519: At the request of Pope Leo X, Michelangelo begins work on the Medici Chapel in the Church of San Lorenzo in Florence, Italy. 1519: Magellan begins his circumnavigation of the globe. 1527: Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, sacks Rome. 34 1536-41: Michelangelo paints the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel. 1543: Nicolaus Copernicus publishes On the Revolutions of Heavenly Spheres. 1547: Henry VIII dies. 1556: Philip II of Spain comes to power after his father, Charles V, abdicates his throne. 1559: Elizabeth I is crowned Queen of England. 1564: Michelangelo dies. 1588: Sir Francis Drake and the English fleet defeat the Spanish Armada. 1609: Galileo first demonstrates the use of the telescope. 1644: The Ming Dynasty in China ends. 1689: Peter the Great becomes czar of Russia. 1776: The American Revolution. 1789: The French Revolution begins and George Washington is elected the first President of the United States. 19th Century: During this century, the Buddha in NOMA’s collection was created. 1804: Napoleon Bonaparte is crowned Emperor of France. 1824: The first steam locomotive is developed. 1840: August Rodin is born in France. 1843: Charles Thurber patents the typewriter. 1844: Mary Stevenson Cassatt is born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania. 1854: Rodin enters the Imperial School of Drawing and Mathematics. 1857: Rodin fails for the third time to gain admission to the École des Beaux-Arts. 1861-65: Mary Cassatt studies painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. 1848: Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto is published. 1859: Charles Darwin publishes On the Origin of Species. 1860: Abraham Lincoln is elected the 16th President of the United States. 1863: Lincoln issues the Emancipation Proclamation. 1864: Rodin joins the workshop of Carrier-Belleuse. 1865: Lincoln is assasinated by John Wilkes Booth. 1866: Mary Cassatt leaves Pennsylvania to study in France. 1870: France loses the Franco Prussian War and the seige of Paris begins. Mary Cassatt returns to Pennsylvania while Rodin flees to Belgium. 1868: The Meiji Restoration in Japan. The capital is moved from Kyoto to Tokyo. 1871: The Great Chicago fires destroys much of the downtown area. 1876: The first telephone call from Alexander 35 1872: Cassatt takes a trip to Parma, Italy to study the Italian masters. 1874: The first Impressionist exhibition takes place in Paris, France. Graham Bell to Thomas Watson. 1884: The Statue of Liberty is presented by France to the United States. 1889: The Eiffel Tower opens in France. 1875: Rodin takes a trip to Italy to study the Renaissance masters. 1892: The “Nutcracker Suite” ballet premieres. 1876: Rodin renews work on Age of Bronze. 1898: Pierre and Marie Curie discover radium 1877: Rodin exhibits Age of Bronze at the Paris Salon. Degas invites Cassatt to join the Impressionists. 1903: The first baseball World Series between the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Boston Pilgrims is played. 1880: Rodin receives a commission for the Gates of Hell. Cassatt begins her studies of women and children. 1914: Archduke Ferdinand of Austria is assasinated in Sarajevo. 1917: The United States enters World War I by declaring war against Germany. 1881: Pablo Picasso born in Málaga, Spain. 1884: The city of Calais, France commissions Rodin to sculpt The Burghers of Calais. 1927: Charles Lindberg is the first to fly solo over the Atlantic. 1929: The Stock Market crashes. 1891: Jacques Lipchitz born in Lithuania. Cassatt has her first solo show at Galerie Durand-Ruel. 1892: Cassatt begins a mural on the modern woman for the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Picasso enters the School of Fine Arts in La Coruña, Spain. 1938: Parker Brothers inttroduce Monopoly. 1941: Japan bombs Pearl Harbor. 1943: Chiang Kai-Shek becomes the president of China. 1897: Picasso enters the Royal Academy of San Fernando in Spain. 1944: US and Allied forces land at Normandy. Early 20th Century: The Pair of Female Ere Ibeji are carved by Olowe of Ise of the Yoruba peoples. 1947: Jackie Robinson of the Brooklyn Dodgers becomes the first black professional baseball player. 1900: The pavillion at the International Exposition in Paris is devoted to a Rodin retrospective. Picasso moves to Paris. 1948: Ghandi is assasinated. 1901: Picasso enters his Blue Period. 1955: Rosa Parks is arrested after refusing to move to the back of a bus. 1953: Dr. Salk develops the polio vaccine. 1904: Picasso begins his Rose period. 1959: Fidel Castro overthrows Batista. 1906: Cassatt paints Mother and Child in the Conservatory. Lipchitz takes attends school in Vilna. 1961: Construction of the Berlin Wall begins. 1907: Picasso begins work on Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. 1968: Martin Luther King, Jr. is assasinated. 1908: Picasso begins his Cubist collaboration with Georges Braque. 1963: John F. Kennedy is assasinated. 1969: Neil Armstrong takes man’s first walk on the moon. 1974: President Nixon resigns. 36 1909: Lipchitz leaves for Paris with his mother’s help. 1977: Apple II, the first personal computer goes on sale. 1910: Picasso paints David-Henry Kahnweiler. 1913: Lipchitz meets and befriends Picasso. Begins interest in Cubism. 1981: Prince Charles weds Lady Diana Spencer in England. 1990: The Berlin Wall is demolished. 1914: Cassatt stops painting due to blindness. 1916: Lipchitz begins work on Bather. Picasso begins his collaboration with Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes. 1917: Rodin dies in France. 1919: Mary Carson Catlett is born in Washington D.C. 1920: Lipchitz has first large one-man show. 1926: Cassatt dies in France. 1933: Catlett graduates from Dunbar High School and enters Howard University. 1937: Picasso installs Guernica in the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair. 1938: Olowe of Ise, the sculptor of the Ere Ibeji, dies. Catlett graduates from Howard University with a B.S. in art. Lipchitz exhibits Prometheus Strangling the Vulture at the Paris World’s Fair. 1940: Catlett is awarded an M.F.A. in sculpture from the University of Iowa, where she studied under Grant Wood. She later moves to New Orleans and accepts a position at Dillard University. Picasso has a major retrospective of his work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. 1941: Catlett spends the summer studying at the Art Institute of Chicago and working with WPA artists. 1942-43: Catlett moves to the East Coast. 1944: Catlett joins the faculty of George Washington Carver School in Harlem. 1945: Catlett is awarded the Julius Rosenwald Foundation grant to produce a series on Black women. 1946: Catlett moves to Mexico enabling her to concentrate on her own work. She joins the Taller de Gráfica Popular, an artistic workshop for the 37 1997: Scientists in Scotland clone a sheep named “Dolly.” common man. 1947: Catlett marries Francisco Mora in Mexico. 1953: Picasso meets Jacqueline Roque, the model in Woman in an Armchair. 1954: Lipchitz has a major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. 1958: Catlett is hired as a sculpture teacher for the School of Fine Arts, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. 1960: Picasso completes Woman in an Armchair. 1961: Picasso marries Jacqueline Roque. 1963: Catlett is awarded the Tlatilco Prize at the First Sculpture Biennial in Mexico. 1973: Picasso dies. Lipchitz dies. 1975-78: Catlett creates and presents a ten foot bronze of Louis Armstrong for the City of New Orleans’s Bicentennial celebration. 1983: Catlett has a solo exhibition at the New Orleans Museum of Art. 38 Curriculum Objectives Geography: *Draw a map of one of the countries that the artists come from. Fill it with a collage that reflects elements of that culture. *Ask students if they were to visit all the sites or artists mentioned, what would be the most practical route? *Discuss trade in Africa and the East. How has it influenced western artists? Mathematics: *Discuss different systems of measurements throughout history. How have they become standardized? Where did our own system come from? *Have students measure the length of their index finger. Is this measurement an accurate unit for the rest of their body? Is there a simple ratio that can be applied? Science: *Investigate how bodies move. What are the specific muscles that are used? *Look at and discuss other artists who were interested in the human body such as Leonardo da Vinci or Thomas Eakins. What contributions in the scientific field have influenced them? *Discuss properties of bronze, marble and clay. Why do they make good mediums? What do they say about the cultures who used them? Language Art: *Have students create stories about the characters in the slides. What are they doing? What are they feeling? *Have the students write a poetic self-portrait or a portrait of someone that they know or admire. *Read and discuss Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad. What are the author’s perceptions of African culture? Social Studies: *Discuss the influence of religions upon art. *Discuss the presence of religious symbols in art. What are some particular symbols and what do they mean? *Discuss different cultural climates and rituals. How are they reflected in art and body types? *Who are Socrates and Plato? Read short excerpts of their writings and discuss their philosophies on beauty. *Discuss images of beauty in today’s society. Are they healthy or harmful? Do other cultures share the same ideals? *Discuss body decoration in different cultures. How do we decorate our bodies today? 39 Visual Arts: *Discuss abstraction versus realism. *Create a realistic self-portrait. Use it to make an abstract version. *Discuss symmetry, balance and order. How do these concepts relate to Greek sculpture? Do these terms still have relevance in today’s art world? *Observe the texture and detail in the paintings and sculptures. How do they effect the work of art? *Discuss the technique of mosaic. Have students make their own mosaic out of colored pieces of paper or stones. *Discuss folk and ritual dance. Have the students create their own dance and explain its meaning. *Create a collage self-portrait. 40 Bibliography Arnason, H. H. History of Modern Art, Third Edition. New York: Harry N. Abrams and Prentice-Hall, 1986. Breeskin, Adelyn Dohme. Mary Cassatt: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Oils, Pastels, and Drawings. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1970. Watercolors, Bullard, E. John. Mary Cassatt: Oils and Pastels. New York: Watson-Guptill, 1972. Elsen, Albert E. “Rodin as Spokesman of the Unspeakable,” in Rodin and His Contemporaries: The Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Collection. New York: Cross River Press, 1991. Fergonzi, Flavio. “The Discovery of Michelangelo: Some Thoughts on Rodin’s Week in Florence and Its Consequences,” in Rodin and Michelangelo: A Study in Artistic Inspiration, eds. Flavio Fergonzi, Maria Mimita Lamberti, Pina Ragionieri and Christopher Riopelle. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1997. Gupte, R. S. Iconography of the Hindus, Buddhists and Jains. Bombay: D. B. Taraporevala Sons, 1972. Hammacher, A. M. Jacques Lipchitz, trans. James Brockway. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1975. --------. Jacques Lipchitz: His Sculpture, intro. Jacques Lipchitz, New York: Harry N. Abrams, no date. Levkoff, Mary L. Rodin: In His Time. New York: Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Thames Hudson, 1994. Lewis, Samella. The Art of Elizabeth Catlett. Claremont, CA: Hancraft Studios, 1984. Mason, Penelope. History of Japanese Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1995. Riopelle, Christopher. “Rodin Confronts Michelangelo,” in Rodin and Michelangelo: A Study of Artistic Inspiration, eds. Flavio Fergonzi, Maria Mimita Lamberti, Pina Ragionieri and Christopher Riopelle. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1997. Stokstad, Marilyn. Art History, revised edition. New York: Harry N. Abrams and Prentice Hall, 1995. Tancock, John L. The Sculpture of Auguste Rodin. Boston: David R. Godine, 1976. Wardwell, Allen, ed. Yoruba: Nine Centuries of African Art and Thought. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989. 41