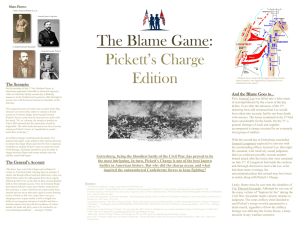

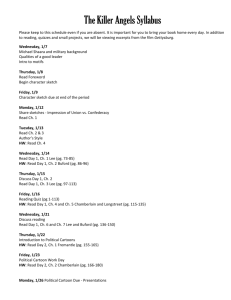

Lt. Gen. James Longstreet

advertisement