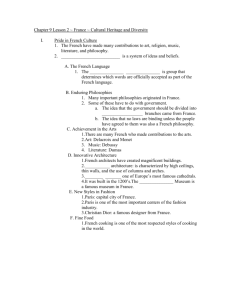

Who Are We?

advertisement