See Full Article

advertisement

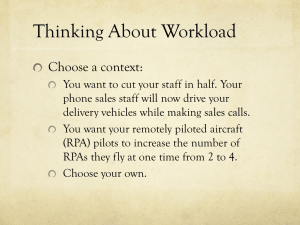

Prime Journal of Business Administration and Management (BAM) ISSN: 2251-1261. Vol. 3(8), pp. 1140-1148, August 31st, 2013 www.primejournal.org/BAM © Prime Journals Full Length Research Paper Academic Workload - Does it affect talent management in public universities in Kenya? Alice W. Kamau, Roselyn W. Gakure, and Anthony G. Waititu Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT), Nairobi CBD Centre, Box 62000 00200, Nairobi, Kenya. th Accepted 8 August, 2013 In spite of higher institutions of learning being regarded as producers of knowledge (Lynch, 2007) disseminators of knowledge and stimulators of intellectual life (Oketch, 2003) they do not value talent management as the private sectors (Riccio, 2010). Kenyan universities like many other universities have a slow pace or lack talent management as noted by (Ngome, 2007). This paper is anchored on a study on factors affecting talent management in the public universities in Kenya. On this paper, academic workload is focused on as one of the factors. To achieve this objective, a sample of 251 was selected using stratified random sampling from public universities in Kenya. Data was analysed using SPSS to get statistical values to determine the relationship. Q-Q plot, Factor analysis, Bartlett’s test, Cronbach alpha coefficient, and regression analysis were carried out. The analysis revealed a positive relationship between academic workload and talent management. The study recommends cut-offs on part-time jobs in addition to the normal workload to ensure quality is enhanced. The study also recommends work-life balance to increase motivation and talent management in higher learning institutions. Key words: Recruitment, training and development, motivation, succession plan, employees retention. INTRODUCTION Certified Institute of Personnel Development (CIPD, 2010) defined talent management as the systematic attraction, identification, development, engagement or retention and deployment of those individuals who are of particular value to an organization, either in view of their high potential for the future or because they are fulfilling business or operation critical roles. Talent consists of those individuals who can make a difference to organizational performance, either through their immediate contribution or in the longer-term by demonstrating the highest levels of potential (CIPD, 2010). The concept of talent management was derived from World War II (Cappelli, 2008) and its strategic importance was realized when McKinsey Consultants Group conducted a study on War for talent in late 1990‟s as cited by Scullion and Collings (2010). The war for talent was prompted by the realization that talent shortages were increasingly becoming one of the biggest human resource concerns for multinational corporations (Makela and Bjorkman, 2010). The specific management of talent has been widely seen as a solution for the HR challenges in today‟s labour market (Lewis and Heckman, 2006; Ritz and Sinelli, 2010; Schuler et al., 2010). According to Fulmer and Conger (2004) the purpose of talent management is to provide a deep supply of valuable employees continuously throughout the institutions. Collings and Mellahi (2009) observed that employees‟ knowledge, skills and competencies are important competitive weapon; hence talent needs to be recognized and natured as one of the discrete source of organizational competitive advantage. To illustrate the urgency to address talent management at colleges and universities, one prediction estimated at least a 50% turnover rate among senior higher education administrators within the next five to ten years (Leubsdorf, 2006). A survey by Talent Pulse (2005) of over 1,400 HR practitioners worldwide by Deloitte 1141 Prim. J. Bus. Admin. Manage. Consultancy, reported that the most critical people management issues are attracting and retaining high calibre workers. A 2007 study conducted by the American Council on Education (ACE, 2007) addressing the characteristics of senior officers in higher education found that less than half (49.0%) of the senior administrators were promoted to their current positions internally. This study illustrated the need to improve talent management within colleges and universities in order to increase the level of readiness among high potential employees (King and Gomez, 2007). Talent management in developing countries Many African countries have lost some of their highly skilled professionals to the United States, Canada, France, the United Kingdom, Australia and the Gulf States; consequently most universities rely on individuals who have not acquired their highest level of academic training as lecturers. Elegbe (2011) observed that it is a paradox in Africa that although the unemployment rate is high, organizations are complaining of shortage of talent. The African Association for Public Administration and Management (AAPAM, 2008) noted that African Continent has not been able to recruit and retain needed well trained and skilled personnel due to challenges which include among others poor compensation and an uncompetitive working environment. According to Mihyo (2007) the most critical element to be given utmost attention in academic institutions is human capital which includes academic, administrative and technical staff resources however all developed countries are engaged in a struggle to attract talent and reduce the migration of their skilled professionals to other countries. Talent management in universities in Kenya Lewa (2009) noted that in Kenya traditional techniques of talent management and forecasting that are in use today became less useful in the 1980‟s because of turbulence in operating environments. Modern developments in the world have engendered the use of sophisticated models in talent management and forecasting. According to Chacha (2004) most of these institutions are relying on individuals who have not acquired the highest level of academic training as lecturers thereby making the quality of graduates questionable. To improve efficiency and effectiveness in delivery of services, the academic staff must be trained continually in relevant areas. It is therefore prudent for universities to manage talent properly, among other things, in order to ensure their future survival. Theoretical review Several theories reviewed included the PersonEnvironment Theory, Theory Y and Theory X of McGregory, Herzberg‟s motivation-hygiene Theory, and Equity Theory. This paper however concentrates on the Person-Environment Theory which relates to the subject under discussion more than the others. Person-Environment Theory This theory explains a dynamic approach of matching a person with an occupation. The P-E fit perspective explicitly assumes that people and environment change continually in an ongoing adjustment (Chartland, 1991) and that people seek congruent environments. Holland theory is used to illustrate the P-E fit theory. Holland (1992) described his assumption about people and environment acting on each other as the interactive components; he claimed jobs change people and people change jobs. In this regard Holland theory may be summarised up in the following assumptions; (i) most people can be categorised as one of six types realistic, investigative, artistics, social, enterprising or conventional; (ii) there are six model environments, realistic, investigative, artistics, social, enterprising or conventional; (iii) people search for environments that will let them exercise their skills and abilities express their attitudes and values and take on agreeable problems and roles. Holland claimed that people seek environments that are compatible with their values and attitudes and that allow them to use their skills and abilities; further the behaviour is determined by interactions between the individual and the environment and determines contextual factors such as job satisfaction stability and achievement, education choice and personal competence and susceptibility to influence. A refinement of Holland‟s have emphasised that an individual heredity and interactions with their environment contribute to the development of type and that vocational predictions work better when contextual variables such as age, gender and social economic status are taken into account. Holland (1997) discussed the relationship between an individual and the environment in terms of congruence, satisfaction and reinforcement; and suggested that incongruence is resolved by changing jobs, changing behaviour and perception. In applying Holland‟s theory and based on the meaning of talent management, people tend to be attracted to an institution if they perceive that the environment is compatible with their personality or individual needs. Those already in employment tend to remain with the institution if there is sense of achievement through personal development which is realised by providing growth opportunities. However Holland theory remain descriptive with little emphasis on explaining the causes and timing of developmental hierarchies of the personal modal styles; he concentrated on factors that influence career choice rather than on developmental process that leads to career choice (Zunker, 1994). It has also been criticized for not adequately addressing the career development of women, racial and ethnic and other groups. Empirical review According to Howard (1999), faculty workload should be defined as a mix of three basic areas of faculty activities, Kamau et al., 1142 the proportion of which can differ just as relative weight institutions accord these categories does. These areas include teaching, research and services. Howard explains the activities as follows; - Teaching: it consists of far more than what takes place during the few hours a week that faculty members spend in their classrooms; many other tasks such as class design, preparation, grading and meeting with students make teaching a complex process. Individual instructions to the students of masters and PhDs require patience, devotion and skills. - Research: according to Bowen and Schuster (1981) as cited by Howard (1991) noted that research is not a process but a product which is why publication is crucial. The products of original research, published books and articles become teaching tools and extend an institutions mission beyond the campus. - Services: follow under two categories as suggested by Howard that is institutional and professional. Institutional services include administrative duties, committee work and students activities. Professional service refers to the work done in support of one‟s academic discipline and involves activities such as serving in committees and boards of professional organizations, organizing or chairing sessions at national or international meetings, editing or reading manuscripts for professional journals or participating in on site program evaluations. Academic workload is the total professional effort, which comprises the time (and vigor) devoted to class management, evaluating student work, curriculum and program deliberation, and research activities. Allen (1996) defined workload as the total amount of time a faculty member devotes to activities like teaching, research, administration, and community services etc. Faculty workload can be described as the full spectrum of work commitments of an academic staff member in an academic unit at an institution of higher education. This comprises work that contributes to the academic enterprise and as agreed upon in considerable detail on an annual basis between the academic staff member and his/her direct supervisor and/or institution. Porter and Umbach (2000) and Glazer and Henry (1994) discussed that faculty workload covers multi factors besides teaching credit hours: committee involvement, research time, community service, office hours, student evaluation, and course preparation. They group the faculty activities in domains of instruction, scholarship, and service. Austin (2002) and Tettey (2010) assert that the workload that accompanies responsibility for large student numbers imposes significant career-stalling burdens on young scholars; anxiety that comes with such a burden, in a context that demands high standards of research productivity, can discourage potential academics. In order to address this concern, institutions need to provide relief to those in the early stages of their careers by giving course releases, not assigning them the most highly-subscribed courses, and providing access to professional development opportunities that enable the acquisition of pedagogical skills and an aptitude for balancing the multiple demands of academia and personal life. In highlighting the benefits of reduced workload, Shulkin and Tilly (2005), assert that in order to retain high-talent individuals who value being highly engaged in both work and personal life, reduced workload arrangements should be part of human resource strategies of any employer. Barnett and Hall (2001) also observed that reduced workload is a new weapon for winning the war for talent and retaining professionals with valuable skills. Bond, Thompson, Galinsky, and Prottas, (2002), acknowledged that reduced- workload helps organizations adapt to the realities of a changing workforce and helps foster increased diversity in the management and professional ranks. The benefits suggested by Kossek, Lee, and Hall (2007) include cost savings in pay, increased focus on crucial projects and tasks when on the job; the ability to attract and retain top performers; further coworker relationships and communication are improved and backup training systems and subordinate development are also enhanced. Today work–life balance has emerged as one of the highest recruitment and retention criterion; talented people want to work on what matters most to their firms but in a way that still enables them to live their total life dreams or simply be dually engaged in career and family or personal interests. Employers who do not offer customized work options or who implement them poorly when available will not be employers of choice. Furthermore if the workload of faculty members is higher it leads to a downfall in job satisfaction and the outcome would be poor academic quality (Shahzad et al., 2010). According to Comm and Mathaisel (2003) as highlighted by Shahzad et al. (2010) Universities ought to offer a competitive compensation and workload for attracting and retaining competent workers in higher learning institutions. This connection is important because it enhances the commitment of faculty to performance and acts as a key factor to improve academic quality. Comm and Mathaisel (2000) on employees‟ satisfaction in higher education found workload, working environment, and pay and benefits to be the key factors of employees‟ satisfaction. Faculty is most concerned with salaries and wishes to have stable job and salary with fair promotion (Chen et al., 2006). Metle (2003) found that work content is an important factor in determining employee‟s satisfaction. Hence there can be a connection between intensity of work and level of job satisfaction. Faculty who teach more credit hours which is related to their area of research are more satisfied than those who are involved in teaching more credit hours that is not related to their area of interest. Faculty workload covers the total set of formal and 1143 Prim. J. Bus. Admin. Manage. Table 1: KMO and Bartlett's Test Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. Approx. Chi-Square Bartlett's Test of Sphericity .677 161.666 Df 21 Sig. .000 Table 2: Academic Workload Component Matrix Component Matrixa Component 1 Comfortable with Lecturing Hours Per week .700 Enough time for research and publications .652 Have adequate time for personal engagement .622 I am overworked at my place of work .601 Workload not a hindrance to self development .572 More free time to engage in part timing in other institutions .329 Engaged in administrative work in my Institution Extraction Method: Principal component analysis informal job descriptions. A lot of other factors also affect this package of job description for example department size, nature of institution amongst others. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY A survey research design was adopted using triangulation approach on data, analyst, theories and methodologies. Using stratified random sampling, 251 academic staff was sampled out of 5673 from seven public universities in Kenya. Questionnaires were dropped and picked as tools of data collection. The response rate was 99.2%. SPSS was used to analyse the collected data. RESEARCH FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO) As shown on the table 1, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) has a value of 0.677 greater than 0.5 the minimum value required hence the sample is adequate for factor analysis. Barlett‟s Test of Sphericity indicates value of significance as 0.000 a value less that the predetermined value of 0.05. This shows that there are some relationships between the variables and therefore the correlation matrix of academic workload is not an identity matrix. Factor analysis The table 2 shows the factor loadings for the one component extracted. In this study a threshold of a value of 0.4 is used. Beaumont (2012) argued to disregard those loadings below this threshold and therefore two factors are eliminated from this component; these include -.054 more "More free time to engage in part timing in other institutions" (AW5) and "I am engaged in administrative work in my Institution" (AW3) with threshold of 0.329 and -0.54 respectively. The remaining factors have a factor loading of values above 0.4. Higher values mean closer relationship hence factor analysis is appropriate. Descriptive analysis The items under academic workload included: I am comfortable with the number of lecturing hours/sessions allocated per week in my institution (normal workload); I have adequate time for publications and research; the amount of workload allocated is not a hindrance to self development; I have adequate time for personal engagement and I am overworked at my place of work. Table 3 shows the findings on each item from the respondents: I am comfortable with the number of lecturing hours/sessions allocated per week Those who agreed comparatively to those who disagreed include: 42.6% of the respondents agreeing they are comfortable with the number of lecturing hours allocated to them in their institutions as compared to those who disagreed with 14.1% response rate. Those who highly agreed that they are comfortable have a 24.1% response rate; this adds up to 66.7% response rate of those who affirmed and 17.7% who were on the contrary. I have adequate time for publications and research The respondents who disagreed to this factor were 28.9% and those who highly disagreed 12.9%. Those Kamau et al., 1144 Table 3: Descriptive Analysis - Academic Workload AW1 AW2 AW4 AW6 AW7 Factors related to academic workload I am comfortable with the number of lecturing hours/sessions allocated per week in my institution (normal workload) I have adequate time for publications and research The amount of workload allocated is not a hindrance to self development I have adequate time for personal engagement I am overworked at my place of work Total Mean HA(5) A(4) N(3) D(2) HD(1) 24.1 42.6 15.7 14.1 3.6 8.8 13.3 36.1 28.9 12.9 18.5 26.5 24.1 23.7 7.2 10.4 14.1 12.729 17.3 21.7 24.057 34.1 25.7 23.229 22.9 28.1 26.0 15.3 10.4 14.0 Table 4: Pearson correlation analysis Pearson Correlation Sig. (1-tailed) N Talent Management Academic Workload Talent Management Academic Workload Talent Management Academic Workload who agreed were 21.2% and highly agreed were 8.8%. The results indicated that majority do not have enough time for publication with a 41.8% of the respondents‟ rate. Schulze (2008) found similar results at the South African higher education (HE) institutions where research output was at 1.25 articles per academic per year this number. It is clear from the above that the institution needs to provide time in order to improve research out. The amount of workload allocated is not a hindrance to self development Majority (45%) agreed that amount of workload was not a hindrance to self development. The respondents who disagreed and highly disagreed were 23.7% and 7.2% respectively. These results partially corroborate Mihyo (2007) where staff audit revealed workload heavier for junior staff than senior staff. Similarly Tettety (2010) noted work overload on young scholars in higher education institutions. Therefore the senior staff get more time for research and consultancy which strengthen their capability to publish. I have adequate time for personal engagement These result indicated that work life balance is an issue in higher institutions of learning. The respondents who agreed were 17.3% and 10.4% highly agreed there was no adequate time for personal engagement. Those who disagreed and highly disagreed were 22.9% and 15.3% respectively. This compromises Work-life balance which is explained by Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment Work-life (2012) as effectively managing the juggling act between paid work and other activities that are important to us - including spending time with family, taking part in sport and recreation, volunteering or undertaking further study. Talent management Academic workload 1.000 .302 .302 1.000 . .000 .000 . 249 249 249 249 I am overworked at my place of work The results indicate that academic staffs were not over worked in their respective institutions with 38.5% rate of respondents. Those who disagreed and highly disagreed were 28.1% and 10.4% respectively. Mihyo (2007) study indicated an average workload of staff was eight hours of teaching a week including lectures and tutorials an indication that within respective institutions the academics have normal workload; however he noted that staff workloads in tertiary institutions were not equitably distributed. Similarly, Kipketub (2010) found out an overall work overload due to the additional responsibility beyond the normal required workload for income reasons. Pearson correlation coefficient Table 4 shows Pearson correlation calculated for the relationship between academic workload and talent management. The value of r determines the strength and direction of a relationship between the two variables. The correlation coefficient close to 0 represents a weak relationship. According to Green, Salkind, and Akey, (2000) correlation coefficient of 0.10, 0.30 and 0.50 regardless of the sign, are interpreted as small, medium and large coefficients respectively. A moderate positive relationship was found (r = 0.302, n=249 and p-value <0.05) indicating a significant moderate linear relationship between the two variables. This means that if the value of Academic Workload variable increases, the value of Talent Management variable also increases and vice versa. Goodness of fit model The R squared indicates how much of dependent variable (talent management) can be explained by 1145 Prim. J. Bus. Admin. Manage. Table 5: Model of fit Model R R Square Adjusted R Square 1 .302 .091 .087 Table 6: Regression coefficients Model 1 Unstandardized Coefficients Standardized Coefficients Sig. Std. Error (Constant) 17.340 1.155 - 15.011 .000 Academic Workload .655 .132 .302 4.977 .000 independent variable academic workload. In this case 9.1% of the total variation in Talent Management can be explained by the linear relationship between Academic Workload and Talent Management. This is an overall measure of the strength of association and does not reflect the extent to which academic workload is associated with Talent management. Regression analysis Table 6 shows the regression coefficients of the previously determined model. The regression model y =α3 +β3 x3+ e; α3 is the constant represented by 17.34, β3 is represented by 0.655, a value which indicates the steepness of the regression line or how much the predicted value of the dependent variable (talent management) increases when the value of the independent (academic workload) variable increases. From table 6 both the constant and academic workload contributes significantly to the model. The regression equation takes the form; predicted variable (talent management) = intercept + slope * academic workload. According to Field (2005) the slope indicates how steep the regression line is; the intercept is where the regression line strikes Y axis. Therefore; Talent Management= 17.34+0.655* (Academic Workload). For each Academic Workload value substituted and the Talent Management that results provides an ordered pair that falls on the regression line. This means for every unit increase in academic workload there is a 0.655 change in talent management; indicating that there was linearity in the regression model predicting talent management based on academic workload To test whether the regression coefficient for academic workload was significantly different from zero, the null hypothesis tested was; H0 1 = 0 the H 1 p˃ 0.The P coefficient table 5 signifies the calculated t-value for academic workload equals 4.977, and is statistically significant at p-value 0.000; the tcrit = t247 (0.975) = 1.960; the null hypothesis is rejected and the conclusion was that academic workload has a significant positive influence on talent management. Beta t B How does academic workload influence talent management? This question was answered by regression equation; y =α 3 +β 3 x 3 + e; where β 3 is the coefficient of correlation of academic workload, x 3 is academic workload and y is talent management. Appendix 1 represents the regression line graphically. The line is diagonal reflecting a positive linear relationship between talent management and academic workload. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION From the findings, it can be concluded that though management supported research; individual research and publications were below the expected levels. The study also revealed that academic staffs are allocated normal workloads within their respective institutions; however the amounts of hours spent in part timing can amount to work over load emphasizing further the lack of time for research and publications and personal engagement. The study recommends cut-offs on parttime jobs in addition to the normal workload to ensure quality is enhanced. The study also recommends worklife balance to increase motivation and talent management in higher learning institutions. REFERENCES AAPAM-African Association for Public Administration and Management (2008). Online. www.modernghana.com/.../aapam-conference-callsfor-enhanced-public-service Allen, D.K. (2003).Organizational Climate and Strategic Change in Higher Education: Organizational Insecurity. Higher Education 46: 61-92. American Council On Education(2007). Higher Education development. Online www.acenet.edu/higher-education/.../highereducation-development.aspx Barnett, R., and Hall, D. T. (2011).How to use reduced load to win the war for talent. N Organizational Dynamics, 29(3), 192–210. Kamau et al., 1146 Beaumont J.R (2012). Advanced medical statistics. Online: www.floppybunny.org/robin/web/virtualclas sroom /.../course2.html Bond, J., Thompson, C., Galinsky, E., and Prottas, D. (2002). Highlights of the national study of the 570 changing workforce. New York: Families and Work Institute. Cappelli, P. (2008).Talent Management for the TwentyFirst Century. Harvard Business Review. Chacha, N. C. (2004). Reforming Higher Education In Kenya Challenges, Lessons And Opportunities , State University Of New York Workshop With The Parliamentary Committee On Education, Science And Technology Naivasha, Kenya. CIPD, (2010).The War On Talent? Talent Management Under Human Resource In Uncertain Times. Available at http://www.cipd.co.uk/. Collings, D. and Mellahi, K. (2009). Strategic Talent Management: A Review and Research Agenda. Human Resource Management Review. 19, 304-313. Comm, C. L. and Mathaisel, D. F. X. (2003). A case study of the implications of faculty workload and compensation for improving academic quality. The International Journal of Educational Management, 17 (5), p. 200-210. Comm, C.L. and Mathaisel, D.F.X. (2000),“Assessing employee satisfaction in service firms: anexample in high education”, The Journal of Business and Economic Studies, pp. 43-53, Fairfield, Spring. Elegbe, J.A. (2011). The Challenges of talent management. Talent Scarcity; the Global Scenario. Online. www.ashgate.com/.../Talent-Managementin-the-Developing-World-Elegbe-Ch1.pdf nd Field, A. P.(2005). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. 2 edition, London: Sage. Fulmer, R. M. and Conger, J. A. (2004).Growing Your Company’s Leaders: How Great Organizations Use Succession Management to SustainCompetitive Advantage. New York: American Management Association. Green, S.B., Salkind, N.J. and Akey, T.M. (2000). Using SPSS for Windows: Analyzing and Understanding.Data. 2nd edition, Prentic-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments (3rd ed.). Odessa FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. Howard, G. (1991). „Validating the competing values model as a representation of organizational cultures‟, International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 6(3), pp. 231 Howard, L.W. (1999). Validating the competing values model as a representation on organizational cultures. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 6(3), 231-250. King, J. E., and Gomez, G. G. (2007). On The Pathway To The Presidency: Characteristics Of Higher Education’s Senior Leadership. Retrieved, July 14, 2008 from http://www.cupa-hr.org Kipkebut D.J.(2010). Organizational commitment and job satisfaction in higher education institutions: a Kenyan case. Middlesex University. Kossek, E. E., Lee, M. D., and Hall, D. T. (2007). Making flexible schedules work for everyone. Harvard Management Update, 12(5), 1–3. Leubsdorf, B. (2006). Boomers‘ Retirement May Create Talent Squeeze. Chronicle of Higher Education. 53(2). Academic Search Premier. Lewa, S. (2009).Talent Management and Forecasting in Kenya’s Higher Education Sector: The Case of Public Universities. A Journal of Management, KIM; Nairobi Kenya. Lewis, R. and Heckman, R. (2006). Talent Management: A Critical Review‟. Human Resource Management Review 16: 139-154. Lynch, D. (2007).Can Higher Education Manage Talent? Available at http://www.insidehighered.com/views/2007/11/27/lync h# Makela, K., and Bjorkman, I. E, M. (2010).How Do MNCS Establish Their Talent Pools? Influence On Individuals' Likelihood Of Being Labeled As Talent. Journal of World Business, 45, 134-142. Mihyo. P. (2007). Staff Retention in African Universities and Links with Diaspora Study. Report for the Association for the Development of Education in Africa Working Group on Higher. Ministry Of Business Innovation And Employment Worklife balance, (2012). New Zealand Available http://www.dol.govt.nz/er/bestpractice/worklife. Ngome C., Wesonga, D.; Ouma Odero, D. and Wawire V. (2007). Private Provision Of Higher Education In Kenya . Trends and Issues In Four Universities In Kenya. Oxford; James Curry Ltd. Oketch M (2003). Market Models of Financing Higher Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: Examples from Kenya: Department of Leadership, Policy and Organization: Higher Education Policy: Partner NewsVol No 8; How to understand inequality in Kenya: http://www.ms.dk/sw7605.asp. Porter, S.R., and Umbach, P. (2000). Analyzing FacultyWorkload Data Using Multilevel Modeling. Paper presentedat the AIR 200 Annual Forum, Maryland. Riccio, S. (2010).Talent Management in Higher Education: Developing Emerging Leaders Within theAdministration at Private Colleges and Universities; University of Nebraska – Lincoln Ritz, A., and Sinelli, P. (2010). Talent Management. In A. Ritz and N.Thom (Eds.), (pp. 1–23). Wiesbaden: Gabler. Schuler, R.S., Jackson, S. E, and Tarique, I. (2011). Global talent management and global talent 1147 Prim. J. Bus. Admin. Manage. challenges: Strategic opportunities for IHRM. Journal of World Business, 46:506–516 Schwart, R. Skinner, M. and Bowen,Z. (2009). Faculty Governing Boards and Institutional Governance: Advancing Higher Education, TIAA_CREF Institute Publisher. Scullion, H. and Collings D.G. (2010). Global Talent Management. Journal of World Business, 45, 105108. Shahzad, K., Mumtaz, H., Hayat, K., and Khan, M. A. (2010).Faculty Workload, Compensation Management and Academic Quality in Higher Education of Pakistan:Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction. European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences, 111-120. Shulkin, S., and Tilly, C. (2005). Part-time work. Sloan Work and Family Research Statistics [Online].Retrieved from http://wfnetwork.bc.edu/topic_extended.php?id=10an d type=1and area=academics. Talent Pulse Survey (2005). Becoming a Magnet for Talent. Online.www.deloitte.com/.../a052ad9fed2fb110VgnV CM100000ba42f00aRCRD.htm – Tettey, W. J. (2006).Staff Retention in African Universities: Elements of a Sustainable Strategy. Washington DC: World Bank. Tettey,W.J. (2010).Challenges of Developing And Retaining; The Next Generation Of Academics: Deficits In Academic Staff Capacity At African Universities, Washington DC: World Bank. Umbach, P. (2007). How effective are they? Exploring the impact of contingent faculty on undergraduate education. The Review of Higher Education, 30(2), 91-123. Work-life balance becoming critical to recruitment and retention. (2006). Retrieved from http://www.managementissues.com/display_page.as p?section=researchandid=2981 www.virginia.edu/.../Minorities_in_Higher_Education_200 7 Zunker, V. G. (2006). Career counseling: A holistic approach (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson BrooksCole. Kamau et al., 1148 Appendix 1: Academic Workload Vs Talent Management