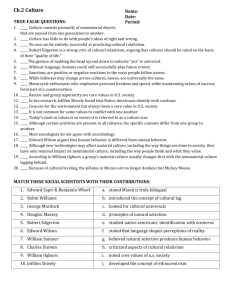

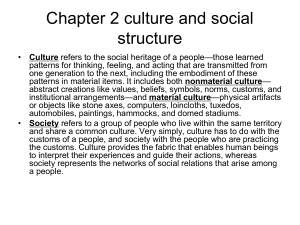

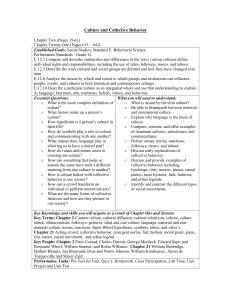

Culture in Sociology

advertisement