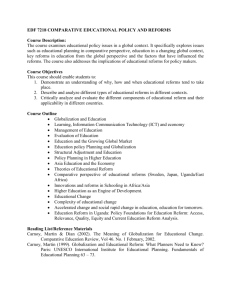

Re-Framing Educational Borrowing as a Policy Strategy.

advertisement