Construction and validation of a nutrition test

advertisement

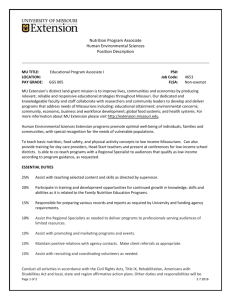

Construction and Validation Of a Nutrition Test Marielle Prefontaine A standardized test to measure nutrition knowledge of a variety of adult groups has been· developed in Canada. Summary A 25-item nutrition test was developed. based on concepts presented by the Interagency Committee on Nutrition Education (ICNE). The goal of the test was a valid. reliable instrument to assess levels of nutrition knowledge of four groups of adults. Objectivity. reliability. and validity are among importa,nt factors in judging quality of a test. In this study. objectivity of the items was ascertained by a group of senior and graduate students in nutrition. The internal consistency measure of reliability was obtained for each group participating in the study. Conte.nt validity was established in two ways: behavioral objectives were based on the leNE concepts and. second. expert judges assessed the relative importance of these objectives. Construct or concurrent validity. the ability of the test to measure performance on a nutrition test. was assessed by testing groups expected to score high or low (based on training they received in nutrition or related fields). Home economics teachers. because of previous training. obtained the highest scores mean score on the test; health science students reached the ideal mean; and mothers and immigrants considered to be lay groups had the lower mean scores. To construct the test the following steps were taken. First, important educational goals for the general adult population were developed based on the ICNE concepts (see Table 1). It was not felt necessary nor desirable to define all goals that could be generated from these concepts; only those recognized as important by authoritative judgments were sought. Table 1 lists the four ICNE concepts and the goals considered as important for the general adult population to make right decisions about food to maintain optimum health. Second, the defined goals were transcribed into operationally defined abilities or behavioral objectives. A series of such objectives was submitted to six dietitians for comments and addition of other relevant objectives. A total of 184 objectives Table I ICNE Concepts and Related Nutrition Goals ICNE concepts Evaluation is an integral part of any educational process. To function effectively, nutrition educators need to gather information on how much a given population knows about nutrition. Evaluation methods can vary all the way from personal judgments to standardized tests. The purpose of this study was to construct a test instrument to evaluate nutrition knowledge which can be applicable to different groups of adults. There have been previous attempts to evaluate nutrition knowledge. In 1956, Young et al. (1) designed a I-hour interview for homemakers which covered topics such as the foods to be eaten daily, the meaning of a balanced diet, the importance of the basic food groups and the nutritive value of substitute foods. Morse et al. (2) administered Kilander's nutrition test to homemakers; no information was given on which topics or aspects of nutrition the test was trying to measure. Eppright and Fox (3) gathered information on the nutrition knowledge of mothers through 35 true-false statements on meal planning, food preparation, and food behavior of their child. McCarthy and Sabry (4) gathered information on nutrition misconceptions of university students through 70 truefalse statements. Dwyer et al. (5) designed a questionnaire for high school students based on nutrition concepts presented in textbooks. From the review of literature, it appears that the approaches used to assess the level of nutrition knowledge were either covering only a limited area of nutrition or were geared to high school students. Construction of Test This study intended to develop a test based on basic nutrition concepts and applicable to a variety of adult groups. To achieve this, the four concepts presented by a subcommittee of the Interagency Committee on Nutrition Education (ICNE) were considered appropriate. These concepts, as Leverton (6) said, summarize all the nutrition knowledge that is applicable to food-for-people-for-health. THE AUTHOR is Associate Professor, Ecole des Sciences Domestiques, Universite de Moncton, Moncton, N.B., Canada. 152 I Journal of NUTRITION EDUCATION Nutrition is the food you eat a,nd how the body uses it. II Food is made up of different nutrients needed for growth and health. Goals formulated by a team of professionals· - To understand the importance and the role of foods - To understand the nutrition needs of the body - To understand the functions of the major nutrie.nts and their food sources. - To understand the importance of a sound and well-balanced diet and to know about different sources of information - To know the recommendations contained in the Canadia,n Food Guide - To understand certain health problems associated with poor eating habits. III All persons. throughout life. have need for the same nutrients but in varying amounts. IV The way food is handled influences the amount of nutrients in food. its safety. appeara,nce and taste. - To understand the nutritional of children - To understand the nutritional of adolescents - To understand the nutritional of adults - To understand the nutritional of pregnancy and lactation - To understand the nutritional of the elderly. requirements requirements requirements requirements requirements - To understand the effect of stor.age on nutritive value. appearance and flavor of food - To know how to freeze fresh and cooked foods - To understand the effects of various cooking methods - To know that the food industry is under government control. *A team of. experts comprising two university professors of nutrition. two profeSSionals In adult education and four graduate students in nutrition arrived at a consensus on what constituted important goals, for the adults, to adequately cover the nutrition field. Vol. 7, No.4. October-December. 1975 were retained as . pertinent abilities required in nutrition for the general adult population. Third, considering that it would be appropriate to produce a short nutrition test, it was decided to reduce the number of behavioral objectives from which the test items would be prepared. Thus a random sample of 100 behavioral objctives was drawn from the 184. Fourth, 100 items based on these selected, objectives were written. The format was that of four multiple-choice items following the procedures described by Ebell (7) and Thornike (8). Fifth, the objectivity of the items was ascertained by a group of senior and graduate students in nutrition. An item was considered objective when there was a consensus that it had only one correct answer of the four alternatives. Sixth, the readability of the items and the timing were checked with different groups of adults: 12 homemakers, 12 secretaries, 12 librarians, 14 adults attending night classes, and 23 freshmen students. When it appeared possible and promising, items were reformulated to increase clarity and modify the proportion of respondents that would agree with the four alternatives of the multiple-choi::e items. Of the 100 items, 26 had to be discarded because it was too difficult to find distractors that would be definitely incorrect but plausibly attractive to the uninformed. Seventh, the remaining items were tested on two groups: one was 111 women adults in waiting rooms of beauty parlors and the other was 93 adults attending night classes. An itemanalysis was done using the Testat Program (9). This program computes (a) the item difficulty index (percent of respondents answering each item correctly), (b) distribution of answers to alternatives (percent of respondents marking each alternative), and (c) the discrimination coefficients (correlations of item scores with total scores on the test in which the item is .included). Thirty items were retained for the nutrition test. The internal consistency measure of reliability, determined by an analysis of variance method, the Richardson's formula (10), was found to be 0.81. This coefficient indicates that the test items represent a relatively homogenous universe of nutrition. 668 students tested represented approximately 72 % of the total population (927). Mothers. This group was sampled randomly from obstetrics departments of the 15 French hospitals in Montreal Island. Twenty percent of the total occupancy on the day of the visit, during October and November 1972, was selected. A research assistant administered 127 nutrition tests. Immigrants. This group was selected from the four Centres d'Orientation et de Formation des Immigrants (COFI) in Metropolitan Montreal. All immigrants who passed their French exam between October 1972 and January 1973 answered a questionnaire under the supervision of a research assistant. Of the 249 questionnaires, 41 had to be discarded since they were incomplete. Table 2 presents the characteristics-sex, years of schooling, age, and previous nutrition training-of these four groups of adults. All home economics teachers reported previous training in nutrition. Some health science students (19%) had taken a course in nutrition besides their training in related fields of nutrition, biology, and physiology. More than one third, 34%, of the mothers had had learning experiences in nutrition at different levels. Results Of the 30 items, 25 had the required discrimination indices (above the 0.30 level). The coefficient of reliability of this 25-item test was 0.68 for the home economics teachers, 0.64 for the health science students, 0.67 for the mothers, and 0.69 for the immigrants. From the 25-item test, an individual's score was obtained by giving a weight of one to each correct answer. The home economics teachers obtained the highest mean score of 19.6; the health science students had a mean score of 15.7, a figure which approached the ideal mean 1 of the test which was 15.9. The mothers and the immigrants obtained mean scores of 12.5 and 10.2, respectively. Table 2 Description of the Four Groups of Adults Participating in the Tryout Programs The Tryout Programs Populations. The 30 item-questionnaire was administered to four groups of adults. These groups were selected because of their various levels of exposure to nutrition or related fields. One group was home economics teachers who had received previous exposure to formal courses in nutrition. The second was students enrolled in their first year of university health science training; they had had some previous training in nutrition. The third group was lay persons with respect to nutrition: a cross-section of mothers having just given birth to a child in hospital. The fourth group was comprised of immigrants; it was felt they would have the least abilities in an unavoidable culture-bound nutrition test. Home Economics Teachers. This group was sampled from French home economics teachers in the province of Quebec. A research assistant mailed a questionnaire during September 1972 to a random sample of 50%; three followups were sent to tardy respondents and by December 1972, 169 completed questionnaires were received, a 64% return. Health Science Freshmen Students. Approval for testing the students was obtained from the directors of the Health Science Section at the Universite de Montreal. The test was given in January 1973 with questionnaires completed during class time under the supervision of a research assistant. The lA point midway between the maximum possible score and the expected chance scores is regarded as the ideal mean. The expected chance score equals the number of items in the test divided by the number of choic9s per item. Since with 25 four-choice items, the expected score is 6.25, the ideal mean in this case is 15.9. Vol. 7, No.4, October-December, 1975 Population Characteristics Sex Male Female Years of schooling <10 years 10-12 years > 12 years Age <25 years 25-30 years >30 years Previous nutrition training With training Without training Home economics teachers n=169 Health science students n=668 Mothers n=127 Immigrants· n=208 '10 % % % 100 48 52 100 55 45 100 100 36 41 23 17 29 54 7 17 76 t t t 40 40 20 32 3S 33 100 19 81 34 66 100 'They came from Latin America (34%), Africa or Asia (28%), Oriental Europe (17%), England, Germany, Australia (16%), and other countries (5%). Sixtysix percent of them were In Canada 4 to 12 months; the others more than one year. tThe specific age of the health science freshman students was not requested but the average of such a group Is approximately 20 years of age. Journal of NUTRITION EDUCATION I 153 The home economics teachers who obtained the highest mean score had had previous courses in nutrition. The mean score of the health science students appears to reflect their training in fields related to nutrition. Within this group, those (19%) who reported previous courses in nutrition obtained higher scores than those without previous courses, p. < .001. With the mothers, the test scores followed the same trend: those who reported previous nutrition courses (34%) obtained higher scores than those without previous courses, p. < .10. When the number of years of schooling was held constant, the influence of previous nutrition courses had a marked effect on the test scores. Of the mothers who reported more than 12 years of schooling, 75% of those who had previous nutrition courses obtained a score above the ideal mean. Although the level of education always appears to be associated with the level of knowledge in nutrition (1-3), it is evident from this study that previous learning experiences in nutrition have a marked effect. It is hoped that nutrition educators in search of an instrument to measure knowledge in nutrition of adult groups will benefit from the expertise, time, and persistence invested in the development of the present nutrition test2 and that they will feel welcome to use it. Project supported by National Health Grant No. 607-7-787 made by the Department of National Health and Welfare (Canada). SA copy of the test in either French or English may be obtained from the author. Spectrum (Continued from page 148) naire before and after exposure to an educational program designed to inform them about nutritional labeling. Nutritional information, along with open dating, unit pricing and names of specific ingredients, was listed as information desired by consumers prior to the educational program. Following the program, total mention of nutritional information increased, but percentage of respondents wanting nutritional information did not greatly exceed the percentage wanting other types of information such as open dating. The article points out that studies in the U.S. indicated a higher degree of consumer preference for nutritional labeling. Often the surveys were concerned only with nutritional labeling, giving the respondents-in effect-a choice of being "for" or "against," rather than stating preferences about different types of labeling information. While this study did not attempt to measure the extent to which consumers would actually dse nutritional labeling, nutrition educators should note that even after a brief educational program on nutritional labeling many of these consumers ranked other label information as having higher priority. Consumer Use of Nutrition Information on Food Labels, Babcock, M.J., Burkart, A., Guthrie, H., Lichtenstein, A. and Thoroughgood, C., New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 844, 154 I Journal of NUTRITION EDUCATION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study was done in 1971-73 at the Institut de Dietetique et de Nutrition, Universire de Montreal. Professors and graduate students as well as professional dietitians and adult educators became involved in this operational research. To all of them, the author expresses her gratitude for their prompt response to her requests for assistance. REFERENCES 1. Young, c., Berresford, K. and Waldner, B.G., What the homemaker knows about nutrition, II: Level of nutrition knowledge, J. Am. Dietet. Assn., 32:29, 1956. 2. Morse, E.F., Clayton, M.M. and Cosgrove, L., Mothers' nutrition knowledge, J. Home Econ., 59:667, 1967. 3. Eppright, E.S. and Fox, H.M., The North Central regional study of diets of pre-school children, J. Home Econ., 62:327, 1970. 4. MoCarthy, E. and Sabry, J.H., Canadian university students' nutrition misconceptions, J. Nutr. Educ., 5: 193, 1973. 5. Dwyer, J.T., Feldman, J.J. and Mayer, J., Nutritional literacy of high school students, J. Nutr. Educ., 2:59, 1970. 6. 'Leverton, R.M., Development of basic nutrition concepts for use in nutrition education, in Proceedings of Nutrition Education Conference, Feb. 20-22, 1967, U. S. Dept. of Agriculture Misc. Pub!. No. 1075, Washington, D.C., 1968. 7. Ebell, R.T., Measuring Educational Achievement, PrenticeHall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1955, pp. 144-181. 8. Thorndike, R.L., Educational Measurement, 2nd ed., American Council on Education, Washington, D.C., 1971. 9. Velman, D.J., Fortran Programming for the Behavioral Sciences, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, Inc., New York, 1967, pp. 178-181. 10. Kuder, G.F. and Richardson, M.W., The theory of estimation of test reliability, Psychometrika, 2:151,1937. Sept. 1975. From Bulletin Clerk, Publications Distribution Center, Cook College, Rutgers University, P.O. Box 231, New Brunswick, NJ 08903,51 pp., single copy free. The chronological development of FDA's nutritional labeling program is outlined in this bulletin along with the purposes of nutritional labeling. Suggestions for minor modification of the present labeling format to improve its usefulness to consumers are also given. A statement in the FDA regulation governing labeling indicates that "The Commissioner will review the regulation periodically . . . and will propose and adopt whatever changes are shown to be in the public interest." The main change recommended by the authors is to list all data for one standardized reference portion size defined by food energy content (with household measures and weights also given) so foods can be compared on an equal calorie basis. Thus, on-the-spot comparison shopping for nutritious foods would be made easier. The authors also recommend the adoption of average RDAs for a typical family. They argue that by including average energy allowance it would be easier to develop popular nutrition education materials utilizing nutrient-calorie relationships (nutrient density) for meal planning purposes. Another recommendation is to list typical or year-round average values for certain products which can vary in l'lutritive value (such as vegetables) to make the data consistent with USDA food composition tables. The authors feel strongly about increasing the usefulness of nutrition labeling to the average consumer and feel these recommendations if implemented would contribute to that end. Lactose Intolerance Milk intolerance and malnutrition, Bradfield, R.B., Jelliffe, D.B. and Ifekwunigwe, A., Lancet, 2:325, Aug. 16, 1975. In a letter to the editor, the subject of milk intolerance (due to lactose content) in the malnourished child living in the tropics is discussed. The authors point out that "while milk intolerance in the well-nourished child living in temperate areas is, at best, disagreeable, it may be catastrophic for the malnourished child living in the tropics." Dry skim milk powder is often the lowest-cost and readily available food available for famine relief. The authors suggest the addition of other nutrients, such as fat and sucrose, would have the beneficial effect of reducing the relative lactose concentration while providing a higher-energy food mix for "catch up" growth. Enzyme treatment of milk, Agricultural Research, USDA, 24(No.2):6, August 1975. Lactose-intolerant individuals may one day be able to drink a special enzymetreated milk without suffering the usual symptoms of lactose intolerance. Milk treated with lactase enzyme (derived from yeast) is more easily tolerated by (Continued on page 172) Vol. 7, No.4, October·December, 1975