The Resurrection of Bell v. Wolfish and the Questions to

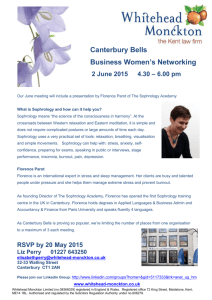

advertisement