FM-2-91.4-Intelligence-Support-to-Urban

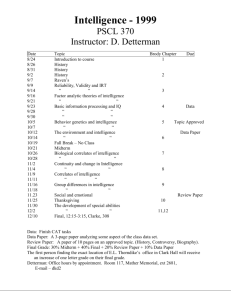

advertisement