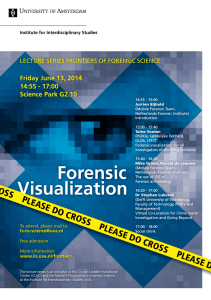

invalid forensic science testimony and wrongful convictions

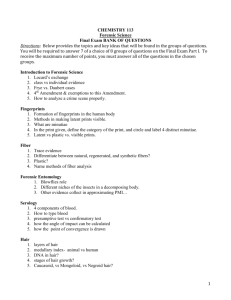

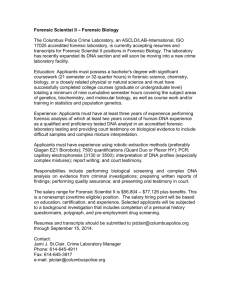

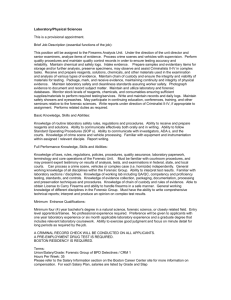

advertisement