chapter 2 career concerns according to super's theory

advertisement

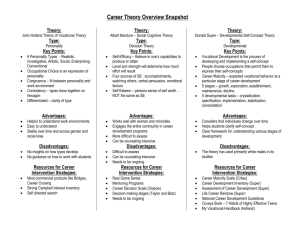

13 CHAPTER 2 CAREER CONCERNS ACCORDING TO SUPER’S THEORY 2.1 INTRODUCTION Effective career development has become essential for the career success of all adults faced with the challenges of this new millennium. As described in the first chapter of this thesis, the close of the twentieth century was characterised by a rapidly changing world of work, that brought about this need for all modern workers to constantly re-evaluate their careers and to create job opportunities that would be independent of any specific organisation. This is also of particular relevance in South Africa. Considering the most recently available labour statistics of the Republic of South Africa, one of the major existential roots of career concerns is easily identifiable, namely unemployment. According to the Central Statistical Services (1995) unemployment figures could be as high as 32,6 percent of the potentially employable population. Since there has also been a vast disparity between the number of people entering the labour market and the annual increase in jobs, one can assume that the percentage is currently even higher (Finnemore, 1999). Unemployment is however only one of the labour concerns of the modern worker in South Africa, as organisational downsizing is causing a rise in the number of early retirements and economic factors cause many workers to be employed in jobs other than their preferred occupations. These challenges are not unique to South Africa, as many developed countries are also experiencing the demands of underemployment and organisational downsizing on their workers. These labour problems are but some of the roots of the challenges posed to, and concerns of the modern worker, which underlines the need for a practical theory of career development in our contemporary society. The relevance, accuracy and value of existing theories have to be examined. Donald E. Super’s work spanning from 1953 to 1996 can be seen as one of the most prominent career development theories of the previous century. It is a 14 well-respected theory that provides a basis for the understanding of the construct of career concerns as moderated by the various stages of development of a person’s life. Seen as a segmented theory by many (Salomone, 1996), it may nonetheless be regarded as one of the most inclusive theories describing the factors affecting a person’s career. Career concerns can be operationally defined by means of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory (Super, Thompson & Lindeman, 1988). In order to adequately evaluate Super’s theory in terms of its relevance to the contemporary South African context, and in particular as it relates to adults, the foundations of the theory will firstly be discussed and then the various models comprising the theory will be described. The relevant research pertaining to the theory will be discussed next, and then the theory will be evaluated in the light of the above. Also, since this thesis deals specifically with the career concerns of adults, the Adult Career Concerns Inventory (Super et al., 1988) and related research will be described, before the value and relevance of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory are examined. The primary purpose of this description is to set the stage for this study of career concerns of South African adults in as far as it relates to career barriers experienced, and the ability to be resilient when faced by these concerns. 2.2 FOUNDATIONS OF SUPER’S THEORY One of the purposes of Super’s earlier work was to integrate a variety of theories of vocational development, namely trait-and-factor theory, socialsystems theory and personality theory. According to this model of vocational development both intra- and interpersonal variables are determinants of vocational behaviour. Thus socio-economic factors, for instance the labour market and family finance, traits and factors, such as values, attitudes, personality, motivation and intellect, personality development, for instance selfconcept or reaction to success or failure, vocational developmental tasks as well as vocational developmental opportunities all contribute to vocational choice (Super & Branbach, 1957). As introduction to Super’s work the basic postulates and propositions of Super’s theory need to be briefly mentioned. In his critical analysis of Super’s 15 theory over a forty year period Salomone (1996) concludes that only ten of Super’s original 1953 propositions have been retained over the years, as well as two from 1957. The theory rests on the notions that people have different abilities, interests and personalities, which qualify them for different occupations. Each occupation requires a different pattern of these characteristics, but choice is always a determining factor. Super and Branbach’s (1957) propositions described vocational development as ongoing, continuous, generally irreversible, orderly and predictable. Vocational development was also seen as a dynamic process involving compromise and synthesis. This process of synthesis or compromise occurs between the individual and certain social factors, and between the self-concept and reality through role-playing, amongst other things. Vocational preferences and competencies, work situations and self-concepts are all inconstant, although the stability of self-concept from late adolescence results in the continuous process of vocational choice and adjustment. Satisfaction (both vocational and avocational) occurs when individuals are in the position to realise their abilities, interests, personality traits, values and so forth (Super, 1984). Pertinent to the career resilience construct described in chapter five, Bell, Super and Dunn (1988) postulate that career maturity is the readiness to meet developmental tasks, and it relates to the coping behaviours of drifting, floundering, trial, instrumentation, establishment, stagnation and disengagement. In addition, Super (1984) differentiates between maxicycles (major life stages) and minicycles (transitions between maxicycles) (Salomone, 1996). 2.3 MODELS IN SUPER’S THEORY The fifty years of theoretical explications by Super have resulted in a fragmented and compartmentalised theory of career development, as mentioned above. The theory can nonetheless be organised into six basic models, namely the rainbow model, the maturity or adaptability model, the salience model, the model of determinants, the career decision-making model and lastly the C-DAC model (Super, Osborne, Walsh, Brown & Niles, 1992). Primarily the aim of career development theory is to describe vocational choice and adjustment (Super et al., 1988). 16 2.3.1 The rainbow model The life-career rainbow (see figure 2.1) depicts the two prominent dimensions of career development, namely life-span and life-space. It relates to the selfconcept and determines the way in which careers are seen (Super, 1980). A separate description of each of these facets follows. Figure 2.1: 2.3.1.1 The life-career rainbow (Sharf, 1995, p. 150) Career stages Career stages relate to the life-span dimension of the rainbow. An individual’s life stages of childhood, adolescence, adulthood, middlessence and senescence respectively coincide with career stages of growth, exploration, establishment, maintenance and disengagement. Three or four major developmental tasks characterise each of the career stages as follows: 17 The growth stage (ages four to thirteen) includes tasks of becoming concerned with the future, increasing personal control over one’s life, convincing oneself to achieve in school and at work, and acquiring competent work habits and attitudes. The developmental tasks of the exploration stage (age fourteen to twenty four) are crystallising, specifying and implementing one’s occupational choice (Super, 1980). The career stages of adulthood, which are of specific relevance to this study, include the stages of establishment, maintenance, as well as disengagement. Adults aged approximately twenty five to forty four encounter tasks of stabilising, consolidating and advancing in vocational positions during the establishment stage (Super, 1980). Stabilising implies remaining in a job for at least a couple of months, learning to meet job requirements, but still being apprehensive about one’s competencies. Once adults reach their late twenties, a unification of different aspects of their careers takes place and is accompanied by feelings of comfort and security, with a need to prove their competence and dependability. Advancing again refers to promotions, or moving to a position with more responsibility, and may entail a higher income (Sharf, 1995). After career establishment adults become concerned with holding on, keeping up and innovating in their careers during the maintenance stage. In the final career stage (disengagement) after the age of sixty five, deceleration, retirement planning and retirement living are common (Super, 1980). In other words, once adults have explored various careers, they are expected to settle down and support themselves and their families, and once settled to strive for job or vocational security in their thirties, before advancing to higher levels of responsibility or income. It is necessary to note that not all adults in the establishment stage will have these concerns (Super et al., 1988). During the maintenance stage (after the age of 45), as said above, adults are required to hold on to their positions, or update their knowledge and skills or even innovate in their field as a result of challenges such as competition, technological change, and so forth (Super et al., 1988). Interestingly, Murphy and Burck (1976) argue that there is a development stage between the establishment and maintenance stages, in particular in the age group between thirty-five and forty-five, which is characterised by the mid-life crisis. This mid-life crisis involves a re-evaluation of one’s self-concept leading 18 to adjustment and change in one’s career. Their proposed stage is referred to as the renewal stage of career development. “Midcareer crises”, according to Super et al. (1988) however, only occur if developmental tasks are not successfully completed. Importantly, re-exploration and re-establishment occur during the transitions between the different career stages (Super, 1980). These transitions often occur at the ages of 18, 40, 60 and 70 (Super, Savickas & Super, 1996). Over and above the re-exploration that takes place between career stages, Super et al. (1988) acknowledge that a change in a person’s major field of activity is becoming increasingly common. An adult may even return to earlier stages, explore new career fields, or change positions in existing fields. Unlike the linear career maturation of adolescents, adults need to “recycle” through the various stages. During the periods of recycling, the adult may face the same developmental tasks of each of the different stages, but in different forms. The participants of this study, being in early adulthood, may recycle through growth (learning to relate to others), exploration (finding desired opportunities), establishment (settling in a position), maintenance (securing the position) and decline (reducing sport participation) for instance (Super, 1994). An interesting comparison can be made between the adult vocational trajectory or spatial-temporal model of Riverin-Simard (1990) and Super’s stages. According to her, there are nine phases in career development, of which the first three are said to compare to Super’s (1957) establishment stage. Phases four, five and six compare with the proposed renewal stage, and the last three phases coincide with Super’s (1980) stage of decline. The possible phases of the participants of this study will be mentioned here. On arrival in the job market, young adults reflect on how to achieve their vocational goals. They then move on to seeking a promising path by questioning their goals and abilities in an attempt to accelerate vocational development. The adult then “grapple with the occupational race”, striving to reach a plateau of occupational status (Riverin-Simard, 1990, p. 132). 19 2.3.1.2 Life roles The life-space dimension of Super’s (1980) rainbow model highlights the importance of the social dimension in a person’s vocational life. A person occupies various social positions and enact six major life roles: child, student, leasurite, citizen, worker and homemaker. During the different stages, two or more social roles are central to a person’s life and codetermine career decisions and other vocational behaviour. Career problems are often symptoms of these role interactions. The establishment stage of adults generally involves the social role of the worker, with conflicts arising due to salience of the homemaker, citizen and leasurite roles. The child and student roles are less important during this stage. During the maintenance stage however, the roles of citizen, leasurite and child could become progressively more important than before, while the worker role remains most salient (Super, 1980). Over and above the six major roles, other roles may also be identified, such as roles of worshipper, lover and so forth. Each role is played in one or more of the theatres of life, of which the most prominent are the home, community, school and other educational institutions and the workplace (Super, 1980). Examining the different roles that adults need to play during the establishment and maintenance phases, gender differences may become apparent. One may think for instance of a woman faced with conflicting roles, such as homemaker versus worker, whereas men may be affected by the arrival of a new child to a much lesser degree. In this regard, Super (1957) identified seven possible career patterns for women. The continuum of career patterns of women ranges from those who may gain no work experience after education in a stable homemaking career to those who have a stable working career by working uninterruptedly throughout their life spans. Super (1957) regards the conventional career pattern as one in which women only work until they get married and then exchange the worker role for the homemaker role. The other career patterns of women are the double-track career (combining worker and homemaker roles), the interrupted career (interchanging worker and homemaker roles), the unstable career (leaving and returning to the work force repeatedly) and the multiple-trial career (many unrelated jobs and therefore no career). 20 21 2.3.1.3 The career The rainbow model clearly encompasses a person’s career from birth to death. Each of the stages occur characteristically between approximate ages. However, there are no definite ages when a stage may commence or end, and one may even recycle through the stages when transitions take place (Super, 1980). For instance, an adult who is retrenched at the age of 45 is in the maintenance career stage according to the rainbow model. However, since the adult has to find a new job, he may be experiencing a need to explore and establish himself in a new career, as would be expected in early adulthood. In terms of this model, career can be defined as the combination or sequence of roles performed by a person in his life-span. The career pattern of the individual is made up of the life cycle, life space and life style. Life style can be defined as the present combination of roles and life space as the sequential combination of roles, which constitutes the life cycle. Earlier success in roles can be seen as predictors of later success. Super (1980) hypothesises that different roles played simultaneously may result in role conflict, but that life style satisfaction and success increases if more roles and diverse roles, are played simultaneously. Over and above the life and career stages, the rainbow also depict affective and behavioural components of the career. According to the shading of the rainbow figure, one can detect the level of emotional involvement in a career, and according to the width of the lines in this figure, the level of active participation in a particular stage can be seen (Super, 1980). 2.3.1.4 Self-concept Super (1957) described the cycle of the working life in terms of the self-concept. Self-concept may be regarded as the way a person sees himself and his situation (Sharf, 1995). It encompasses the subjective perspective on the self, individual abilities, interests and choices and the self-perception within specific roles, situations, functions and relationships. The constellation of self-concepts resulting from the various roles or situations of the individual at a given time is known as a self-concept system (Super, Savickas & Super, 1996). 22 The vocational or role self-concept develops and changes in accordance with perceived reality. Developing vocational identity involves the process of differentiation of the self from others, and simultaneously the process of identification with others. Identification and the development of the vocational self-concept is stimulated by role-playing from childhood onwards. Reality testing, which occurs during the adolescent years, helps the individual to modify vocational decisions (Osipow & Fitzgerald, 1996). The exploration phase is characterised by the development of the self-concept. During the transition from school to work reality testing takes place, and during the trial process in one’s career the individual attempts to implement his or her self-concept. In adulthood the self-concept is modified during the establishment phase. If the establishment phase was successfully completed, the adult has a sense of self-fulfilment. However, if the previous phase was not successfully completed, the adult experiences frustration and insecurity. During the maintenance stage the self-concept is either preserved or it becomes a source of annoyance. Lastly, during the years of decline the adult adjusts to a new self. Super integrated the various types of self-concepts into a system made up of self-concept dimensions and metadimensions (Savickas, 1997). 2.3.1.5 Summary Apparently the life-career rainbow depicts childhood growth, the exploration of teenagers and the career establishment of young adults which culminate in a period of career maintenance. The second half of one’s life is characterised by the end of the maintenance stage and ultimately disengagement. Even though the maintenance stage is regarded as a period of learning and innovation, it can be seen as mere career survival, followed by disengagement, where the focus is predominantly on slowing down and retirement. Simultaneously the salience of various life roles changes throughout these stages as the selfconcept develops. 2.3.2 The model of maturity or adaptability 23 As early as 1964 Super described the concept of vocational maturity as implying a planning orientation to occupational choice, rather than a knowledge of vocational preferences, and he identified a need for an appropriate conceptualisation and measure of vocational maturity in later life stages. Later he defined maturity as the ability to cope with vocational or career development tasks that confront a person (Super, 1977). He differentiated between vocational adjustment which is retrospective and indicates present success and vocational maturity, which is prospective, leading to desired results (Super, 1977). According to this model the five basic dimensions of career maturity are planfulness, exploration, information and decision-making and reality orientation. Planfulness and exploration are the attitudinal dimensions of maturity, whereas knowledge about careers and decision-making are cognitive dimensions (Savickas, 1997). Although these dimensions do not change in adulthood, the content and related tasks of each of these differ for adults. Adults for instance explore different information than adolescents (Super, 1977). Adolescents should have more diversified knowledge and information of different careers as one component of vocational maturity. For adults though ‘vocational maturity’ involves knowledge of information only within their given field (Super, 1977; Super & Kidd, 1979). The type of career information required is dependent on the chosen occupational field, the individual’s life stage, subculture and work role resilience (Super & Kidd, 1979). Following from the above, the “vocational mature” adult could have been described as someone who: (a) has completed the tasks of the exploration stage, and who is performing the tasks of a current stage, albeit tasks of establishment, maintenance or decline; (b) is exploring career information regarding his or her situation, and is aware of or values, and uses his or her resources; (c) has sufficient information about the different life stages and tasks with proper coping behaviours and opportunities; 24 (d) understands and applies constructive decision-making principles, and (e) displays accurate reality orientation in terms of self-knowledge, consistent occupational preferences, clear and certain vocational selfconcepts, and career goals that are appropriate to work experience (Super & Kidd, 1979). Since one of the cognitive components of career maturity, specifically decisionmaking ability, may remain unchanged in adulthood, and since the attitudes required for coping with the various developmental tasks may also remain unchanged, Super (1981) regarded the career maturity construct as inappropriate for adults. Super (1983) prefers the term career adaptability for adults, which still maintains the five basic components of career maturity. Career adaptability is defined as the ability to cope with changing work and working conditions (Super et al., 1988), or to successfully complete the appropriate career development tasks (Super et al., 1992). Adaptability is subjacent to the reciprocal impact of individuals and their environments, as seen in the processes of assimilation and accommodation (Niles, Anderson & Goodnough, 1998). The construct of career maturity denote the fact that adolescents could peak at a level of maturity, as displayed in their career-related competencies and attitudes. The construct of career adaptability on the other hand implies an ability that may either improve or deteriorate during the life span (Super et al., 1992). In other words, an adolescent may become progressively more mature in terms of careers, whereas an adult may, due to psycho-social circumstances, be less or more adaptable during different stages in their careers. Adult career development may initially progress, but then begin to fluctuate and eventually decline (Super et al., 1988). According to Super et al. (1988) the adult career is characterised not only by the entry into, training for and working in an occupation, but relates also to the setbacks faced whilst working and the adaptability required to cope with the changing world circumstances. Savickas (1997) emphasises the importance of the model of adaptability. Adaptability, along with learning and decision-making, is seen as the linking construct for integrating the various segments of Super’s theory from a functionalist point of view. It relates to all four perspectives in Super’s theory, 25 namely the roles of individual differences, career development, the self-concept and the social, historical and social contexts of career-related behaviour and attitudes. Career adaptability is defined as the readiness to cope with both the predictable tasks of the work role and the unpredictable changes in work and working conditions. The planful attitude (planfulness) is central to this construct. The aims of adaptation is to achieve improved person-environment fit (congruence) and to develop the self (self-completion). 2.3.3 The model of career salience The model of career salience is based on the Work Importance Study which involved reviews of the literature on the importance of work from fourteen different countries. According to this model, a work role can be regarded as fundamentally important to an adult, if the adult is emotionally committed to work, actively participates in work and has knowledge of work. An adult has work involvement if he or she is both committed to and participates in work. Work interest is seen if an adult is both engaged in work and has knowledge of it. Lastly, an adult is engaged in work if he or she both has knowledge of work and participates in it (Super, 1982). Thus the meanings of concepts of work involvement, work interest and engagement overlap. Super (1982) differentiates between the absolute importance of a role as defined by the above triangular model, and the relative importance of a role. The relative importance of a career role could for instance be depicted by means of a pie chart showing the various roles in one’s life of which one would be that of the worker. In assessing the salience of any given role with a life career, the Work Importance Study developed instruments to measure participation by means of a time scale, values and the saliency of roles, as seen in commitment, both behavioural and attitudinal participation and once again values. The worker role provides a means of practising various values, such as economic rewards, creativity, intellectual stimulation and so forth (Super, 1982). 2.3.4 The model of career determinants 26 Already in his earlier work Super (1963) stated that possible determinants of career patterns include psychological and physical characteristics and experiences of the individual, the parental family background and one’s own family situation, as well as one’s general situation such as a current job, race, religion, one’s environment, such as a country’s economic conditions and so forth, not forgetting the role of nonpredictable factors, for instance accidents, death, unanticipated opportunities or liabilities. In another early discussion of the dynamics of vocational development Super (1957) had recognised the interplay of various factors, which may include amongst other things, attitudes, interests, personality, the family, economic factors, disability and even chance or uncontrolled or uncontrollable factors in vocational development. Thus the interaction of all these factors results in synthesis or compromise or reality testing. In career development one often has to compromise between reality and preferences, or synthesise personal needs and resources with social or economic demands and resources. Taken together these factors all result in specific role-playing. The model of career determinants is of special value to this study as will be discussed below. The three models described above have already revealed that apart from one’s chronological age or career stage or even life roles, there are also other cognitive, behavioural and attitudinal factors involved in career decisions. The model of career determinants summarises the influences in career development, and specifically, the personal and situational determinants that impact on the life-career rainbow. The specific situational determinants that are identified, are (a) the social structure, (b) historical change, (c) socio-economic organisation and conditions, (d) employment practices, as well as (e) school, community and family influences. Some personal determinants in careers include (a) awareness, (b) attitudes, (c) interests, (d) needs-values, (e) achievement, (f) general and specific aptitudes and even (g) biological heritage (Super, 1980). The most important determinants of career development and resultant career choice, success and satisfaction can be represented by means of the Archway model (Super, 1990). This model, however, does not provide an exhaustive summary of the determinants of a career (Super et al., 1992). 27 Figure 2.2 The archway of career determinants (Sharf, 1995, p. 149). 28 The archway, based on the architectural design of a Norman church door, consists of the following basic divisions: the base, two columns, their capitals and an arch that links the two columns. According to this model, biographical and geographical factors form the basis of any career decision. The two columns and capitals show that career decisions are further determined by, on the one hand the individual, and on the other hand, society. The principle factors associated with the individual is the personality. This accounts for the role of needs, values, interests, intelligence and general and special aptitudes in career development. Personality codetermines one’s level of achievement. As seen in the identical size and shape of the columns, society plays and equally important role in determining careers. The social policies presented by the community, school, family and peer groups, as well as the influences of the economy and the labour market result in the current employment practices (Super, 1990). According to the superimposed arch, one’s specific life stage and role selfconcepts codetermine career decisions, outcomes and behaviours. However, the self is depicted at the centre of the arch (Super et al., 1992), and one may therefore infer that a person is still an active agent in career decisions and not a victim. As decision-maker, the adult needs to synthesise the effects of all the determinants of his career (Super, 1994). 2.3.5 The career decision-making model Throughout his various life stages an individual will reach several decision points, where roles are accepted, relinquished or changed. Adults reach decision points in the worker role between the ages of forty and fifty and between the ages of sixty and seventy. A decision point can be seen as a time of changing roles (Super, 1980). Apart from these specific decision points in time, the individual goes through cyclical decision steps or phases. According to the cyclical decision-making model a person reaching a career decision point asks a decision question, reviews premises and identifies and seeks the necessary data. The person then identifies possible alternatives and the probabilities of outcomes, and weighs up alternatives before selecting a plan. This may be seen as exploration. Once a plan has been selected, the 29 adult may pursue a tentative action plan, evaluate the execution and outcomes of the plan in order to modify it, and then pursue the evolving plan until a new decision point is reached. Alternatively, the adult may pursue and exploratory plan and evaluate the outcomes thereof in order to gain more data that can be evaluated. This may be seen as establishment. Thus the career decision point is simply the beginning of the cyclical process of career decision-making (Super, 1980; Super et al., 1992). 2.3.6 The career development, assessment and counselling model (C-DAC) The C-DAC model can be regarded as a plan to practically apply the principles of the preceding models. A simple matching model is insufficient in describing career choice and adaptation since an individual’s needs, values, interests and circumstances may change (Super et al., 1992). The aim of the model is to improve vocational counselling through proper assessment and the implementation of career development theory. In practice various instruments are used to assess interests, values, the readiness to make career decisions of adolescents and young adults, or the career concerns and developmental tasks of adults and the relative importance of one’s various roles. Two assessment sequences may by used according to the model. In the one sequence career concerns for adults or career maturity for adolescents are assessed first, followed by an assessment of interests, values and lastly role salience. According to the alternative sequence, interests and values are measured before career concerns or maturity, followed again by an assessment of role salience. The latter sequence is especially used for immature students, women who re-enter the labour market, or men who are displaced (Super et al., 1992). The C-DAC model sheds some light on how the Adult Career Concerns Inventory fits into this development theory. It is evident that assessments by means of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory provides only partial information to be used in career counselling. It is also apparent that knowledge of one’s career concerns should be related to information regarding interests, values and the relative saliency of one’s worker role in career counselling. 30 2.4 EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE As one of the foremost theorists in the study of career development, Super’s (1980) theory has generated a tremendous amount of research (Weinrach, 1996). This description of the research on Super’s theory is not meant to be an exhaustive overview of all research findings pertaining to the theory, but merely serves to elucidate the value of this theory to the present study. Only a few of the most relevant and recent findings pertaining to adult career stages, developmental tasks and concerns, career adaptability and the continuous need for exploration will be mentioned. Brief mention will also be made of one study showing some applicability of Super’s theory in the South African context. Smart (1998) found support for Super’s career stage theory. Results specifically showed that satisfaction and involvement progressively increased throughout the exploration, establishment and maintenance stages. Women in the establishment stage were found to be concerned with the development of stable work and personal lives, and participants in the maintenance stage were concerned with holding on to prior accomplishments and maintaining the selfconcept. In an earlier study Ornstein, Cron and Slocum (1989) found that the attitudes of commitment to work, job satisfaction and job involvement of individuals in the establishment and maintenance stages were similar. Murphy and Burck (1976) reviewed findings of seven studies of the sixties and early seventies in support of their notion of a developmental stage between the establishment and maintenance stages. In essence the results of these studies showed that subjects in the age group of thirty-five to forty-five shared common external events and internal experiences which resulted in permanent changes in their lives. Participants in this age group characteristically expressed feelings of anxiety, dissatisfaction, boredom, fear of consequences or personal disappointment, negativity, as well as shared concerns regarding ageing, death and a need for change. The researchers concluded that these findings provide sufficient evidence for the existence of their proposed renewal stage of career development. The validity of the career adaptation concept for adults, as opposed to vocational maturation, was supported by Williams and Savickas (1990). However, inappropriate career concerns for their participants in the maintenance stage were found, such as concerns about preparing for 31 retirement, a need for further education and questioning of future directions and goals. Niles and Anderson (1993) found career concerns applicable to the exploration stage instead of the expected establishment and maintenance concerns for their sample of career counselling clients. Career decisionmaking and recycling seems to occur regardless of chronological age. Anderson and Niles (1995) examined concerns of career counselling clients with a mean age of thirty-five (ranging from twenty-two to fifty). They found that the majority of the participants expressed concern with tasks of the exploration stage. Although the participants were concerned with tasks of other stages, they were reluctant to voice these in the career counselling context. Results also showed that noncareer concerns were often discussed in career counselling. The researchers concluded that career counsellors should assist clients not only with exploration tasks, but also with other career and noncareer concerns. This tendency of continuous career exploration throughout adulthood was corroborated by Niles, Anderson and Goodnough (1998) who found that exploratory behaviour may be used to maintain current positions, to focus on retirement, or even to become more innovative in a current position. These researchers examined how exploration behaviour is used throughout the different adult career development stages in coping with tasks. In addition they studied the relationship between individual life-role salience and career exploration in adulthood. Their findings showed that career exploratory behaviour in adulthood included (a) improving ones’ career while staying in the same position, organisation or field; (b) re-exploring new roles through career recycling or re-entry (new occupations); and (c) innovations and updating within current occupations. Their findings also showed that the life-role salience did not differ for the different types of career explorers. Additional support of the validity of the career concerns concept can be found in Duarte’s (1995) study of career concerns, values and role salience in employed men. The pattern of concerns found were appropriate for the development tasks expected based on the mean age of the participants. Component analyses of the three instruments used also confirmed the distinctiveness of career concerns, values and role salience. 32 In an interesting study comparing the concerns of the theorists Super and Holland themselves at the ages of eighty and seventy-one respectively, Weinrach (1996) found no concerns with tasks of exploration and establishment, and hardly any concerns associated with the maintenance stage for them, as may have been theoretically expected. Only Super expressed slight concern with the disengagement tasks. In essence the results showed that these theorists had no significant career concerns. From the foregoing examples of research on Super’s theory it seems that there is support for the different developmental stages, but that the various career concerns associated with the respective development tasks cannot be limited to any specific developmental stage. In other words, one may infer that current career concerns cannot be predicted merely from the career stage or age of a person, and that concerns with career exploration can be prevalent throughout a person’s career. One may describe deviations from expected results to a variety of mediating variables. The Work Importance Study conducted in South Africa indicated that the importance of life roles and values are influenced by factors such as language, socio-economic status, gender and educational level (Langley, 1995). One should consider these variables as possible determinants or mediating variables in studies pertaining to Super’s work. 2.5 EVALUATION OF SUPER’S THEORY In the introduction to this chapter the need for a pertinent, accurate and useful theory of careers was raised. According to Blustein (1997) the career development perspective of the twenty first century can be based on Super’s work of the last two decades of the previous century. In this section Super’s theory will be evaluated in accordance with the models described above, in order to establish the value of the theory for understanding contemporary adult careers. Specific emphasis will be placed on the premises and research regarding career concerns. The evaluation will commence with criticism of the general value of the theory. Vocational choice will then be examined, before each of the models of the theory will be scrutinised. 33 2.5.1 Value of the theory Super’s perspective of vocations according to Nevill (1987) is not only theoretical, but it is supported by research and is applicable. Osipow and Fitzgerald (1996) describe the theory as being well-ordered, systematic, specific, applicable and empirically supported. Moreover, it is based on differential, developmental, phenomenological and contextual approaches and has not been stagnant, but constantly enriched. Super (1994, p. 64) holds that his theory embraces several theoretical approaches by labelling it “differentialdevelopmental-social-phenomenological psychology”. Although his theory encompasses many fields, his earlier work is predominantly personenvironment theory based and his later work is life span development theory based (Super, 1994). In examining how various career development theories relate to Super’s stages, Sharf (1995) found that apart from the Theory of Work Adjustment and the Myers-Briggs theories, other theories only include Super’s growth and exploration stages, namely theories of traits and factor, Holland, Tiedeman, sequential elimination and social learning, thus illustrating the extensive nature of Super’s work. Blustein (1997) comments on the value of Super’s life-career rainbow model and adaptability model in filling the gaps in understanding of the antecedents and consequences of exploration. The importance of social, economic, historical and cultural contexts, as depicted in the life-career rainbow model as antecedents of exploration and the role of planning, exploring and decisionmaking in coping with the changing world, as depicted in the adaptability model demonstrate the usefulness of the theory. Exploratory skills as well as attitudes are required to adapt to change and ultimately to grow. He also comments on the value of the theory in describing the integration of life roles. Savickas (1997) nonetheless criticises the theory for its lack of deductive explanatory principles, that may be expected from a functionalist theory, as opposed to a mere synergy of existing knowledge. Moreover, the cross-cultural applicability of Super’s theory has also been questioned. In this regard, Stead and Watson (1998) argue that the applicability of Super’s theory in terms of black South Africans is limited, as it does not address issues of ethnic identity, discrimination, unemployment or a culturally applicable world view. De Bruin (1999) also argues that Super’s 34 assumptions regarding career stages are not necessarily applicable in the South African context which is characterised by limited career-related resources in terms of education and socio-economic support. The applicability of Super’s theory with regards to women has also been questioned. Based on findings of a study comparing women and men’s career transitions, Sterrett (1999) concludes that women makes more radical career changes than men. The findings of this study suggest that women’s careers are less linear and stage-related than those of men, and may be better understood in terms of Astin’s (1984) socialisation and expectation model of career development rather than Super’s model. 2.5.2 Vocational choice Probably the most important career task is the choice of a career. Super and Branbach (1957) ascribed career choice not only to personality factors, but also to the influences of cultural factors, developmental tasks and opportunities. Adults in the twenty first century are faced with major vocational choices not only at the beginning of their careers but throughout their life spans. Super (1980) recognises this pattern by describing the transitions that may take place in a career. At various decision points career choices are made. The question remains as to which of the above factors exerts a greater influence on adult career choices. At times opportunities may play a more important role in career choice than interests and values for example. Super and Branbach’s (1957) notion of synthesis and compromise is useful in this regard. An integration of economic and social factors that influence career decisions is required (Osipow & Fitzgerald, 1996). The concept of career status and its influence as described by Gottfredson and Holland (see chapter four) on adult career decisions could prove a useful elaboration of Super’s premises. The model of career determinants is another valuable aspect of Super’s theory as it accounts for the most important variables identified in other career choice theories. Career choice is not merely ascribe to the need to create a match between personality and interests for instance. Instead, the influence of intra- and interpersonal factors, as well as contextual factors are acknowledged. The career decision-making model is a useful description of the cognitive processes in the career. It explains the difference between exploratory decision-making which involves the selection of plans based on alternatives and 35 likely outcomes, and establishment decision-making which involves the process of evaluating the implementation of plans. Not only does the theory display a great value in itself, but it seems to have had a rippling effect in vocational psychology. It has for instance affected theories on the career-decision making process. Particularly, a new definition of adaptive coping can be based on the notion of career uncertainty due to lifespan and life-space changes (Phillips, 1997). 2.5.3 The life-career rainbow model Over and above career choice, one should ask whether the rainbow model is an adequate description of the modern adult’s career. An evaluation of both the life-span and life-space dimensions of the rainbow model follows. 2.5.3.1 The life-span dimension Two questions are tentatively answered in this section of the evaluation: (a) Is it possible to accurately differentiate distinct career stages?; (b) Can specific career concerns be associated with certain career stages as has been theoretically predicted? It is already evident from Super et al.’s (1988) description of the process of recycling through the career stages that these stages are not set in stone so to speak. It has also been mentioned above that Super et al. (1988) recognise the fact that more and more career changes are taking place in middle and late adulthood. London and Greller (1991) ascribe the career reconsiderations taking place not only in the mid and late career to the more turbulent employment situation. Super et al. (1988) also state that the career concerns associated with various stages occur on average for certain age groups, but that great variations may occur. The criticism of Vondracek, Lerner and Schulenberg (1983) against career development theories may apply in this regard, as they purport that for an event to be described as a stage, it must be 36 universal, and present an unvarying sequence of changes, and apply to all individuals. According to them career behaviour should be described in terms of person-context relations instead. It seems that the process of recycling does not fully account for deviations from expected career stages. The notion of recycling which is preceded and followed by periods of stability is questioned by Riverin-Simard (1990). According to her, all stages are characterised by two continually alternating stages of instability, namely goals questioning and means questioning instead. Salomone (1996) also criticises the notion of recycling through all career stages, as all transitions cannot include phases of establishment, maintenance and decline. It is also ironic that, although Super distinguishes between maxicycles and minicycles, he provides no empirical evidence of these notions. The results of the studies discussed above show some support for Super’s careers stages. However, findings also reveal that although support may be found for the disparity of career concerns for different career stages, evidently adults may experience any of the concerns at a given time regardless of career stage. Adults may experience the need to adapt or even start over again with their careers or explore at any age. There is clearly a need for greater comprehension of the variables that may affect an adult who is expected to be in the maintenance stage to recycle or explore new careers. There is also a need for more research on the career stages of adults, and of the adaptation process during career transitions (Super, Savickas & Super, 1996). Furthermore, there has been tentative evidence of an additional career stage, namely the renewal stage (Murphy & Burck, 1976), which should be further studied and integrated into Super’s theory. As a result of the preceding criticism, one may go as far as to say that this model is a broad generalisation of career-related events or tasks that may or may not occur at certain ages and during certain career stages. The participants of the study described in this thesis are theoretically expected to be settled in a job and predominantly striving for security in their job or vocation, and once a feeling of security has been obtained, to strive for more responsibility or a higher income within the boundaries of the same job or vocation. However, if one considers the current South African socio-economic climate mentioned above, deviations from the expected career tasks and 37 concerns may be understood. Many young adults for instance are delayed in the exploration phase of their careers due to unemployment. Others may never advance in a given job since there has been a movement from hierarchical promotions to external recruitment in their organisations. Still others, due to lack of opportunities, may move between various careers in their life span without ever achieving person-job congruence. One may hypothesise that research findings of studies of the career concerns of young South African adults will echo the deviations from the expected developmental tasks of the other research findings described above. When the reality of adult career recycling and the occurrence of reinvented careers are considered, one may argue that the two-dimensional depiction of career stages as a rainbow is in fact an insufficient representation of the premises of the theory. As alternative one may consider representing the career stages in the form of a circle or wheel. If the sequence of career stages are accepted as being correct, the wheel could show how a person moves through various stages. For some the wheel may turn faster as recycling occurs, while others may only experience the first couple of stages in the wheel. Super (1994) in fact believes that different drawings are needed to adequately represent one facet of the theory. A ladder model of life career stages is also inadequate, as it implies a process of climbing, which is not inevitable in careers. One may even question the distinctiveness and sequence of the various stages. The abovementioned empirical evidence seems to suggest that exploratory behaviour may occur throughout different career stages and not only during the exploration stage (Anderson & Niles, 1995; Niles, Anderson & Goodnough, 1998). The question remains whether this is only at distinctive points of recycling, or whether it occurs throughout the career. Nevill (1997) in fact considers exploration as a vital element of our survival mechanism. Since many adults are employed in occupations other than their ideal, one may hypothesise that exploratory behaviour and attitudes may even occur simultaneously as the adult is striving to reach a position of higher responsibility or income in the current and less than ideal position. Super (1980) also suggests that the stage of advancing is followed by a stage of maintenance, where any growth is only related to holding on to a job in adulthood. Career advancement may however 38 occur right to the time of retirement. These are only examples of how the developmental tasks of the various career stages may overlap. Super’s description of the self-concept and its development further elucidates our understanding of careers. According to the theory one may expect that the participants of this study, being in the establishment stage of their careers, are modifying their self-concept with the purpose of achieving self-fulfilment. However, if one accepts the notion that exploration takes place throughout the career, one may also infer in accordance with the theory that adults will adjust their self-concepts throughout their careers according to the reality perceived. One may infer from the preceding discussion that the career stages described by Super could not be seen as an absolute representation of careers today. The most important inference that may be made from the research findings is that, although there is evidence of the various career stages, they may merge for some populations. The universality of the stages in terms of ages may be questioned. One may also conclude that the various stages should not be linked to specific ages. In counselling career development should be viewed independently of age or expected career stage and only in terms of the individual’s career-related concerns. In this regard Smart (1998) suggests that in research career stage should not be operationalised by age, but by using the individual’s current career circumstances and perceptions. 2.5.3.2 The life-space dimension Another pertinent component of the life-career rainbow model is the association that Super (1980) makes between the career stages and other roles performed in one’s life span. The life-space dimension of the model sheds light on the variety of roles performed by adults. Swanson’s (1992) review of research on Super’s theory brought to the light the need for more research on adult life-span, especially of middle-aged and older adults, and adolescent life-space, as well as empirical integration of life-span and life-space research. In the first chapter of this thesis the current importance of holistic development of individuals was described. For instance, one of the critical tasks of Integrative Life Planning is to create a meaningful whole in an adult’s life by connecting 39 family and work life (Hansen, 1996). The career role may no longer overshadow the other roles performed by the individual. According to Savickas (1997) the theory, in describing the life-role dimension of careers, takes into account the multiple contexts of life. Career counselling should therefore be aimed not only at career planning, but at the full development of the individual within their various roles. Career-related behaviour is not only a function of the career stage, but also depends on the saliency of various roles of the adult. The downward slope in late adulthood of the life-career rainbow suggests a decline in the career. If the other roles that the adult performs, such as roles of homemaker or citizen are to be seen as equally important as the worker role for the modern adult, then the depiction of the life-career rainbow once again seems to be inadequate. For instance, a decline in the worker role in late adulthood may be associated with an increase in the leasurite role. Instead of depicting the growth of the leasurite role as the broadening of the leasurite role band on the downward slope of the rainbow, each role should have its own circle to sufficiently represent growth that may take place and the importance of each role. By representing the various roles as concentric circles, the simultaneous establishment of one role and decline of another role may be portrayed. 2.5.4 Vocational adaptability Another valuable aspect of Super’s theory is the differentiation between the model of maturity for adolescents and the vocational adaptability model for adults. The notion of adaptability allows for the influence of change on adult careers. Whereas Super and Kidd’s (1979) description of the vocational mature adult allowed for an understanding of both cognitive and attitudinal requirements in careers, the adaptability concept relates mainly to the attitude of planfulness. Langley (1999) believes that the notion of career adaptability is of specific relevance in the South African context due to the changing nature of the world of work in this country. One may nevertheless say that the value of the theory can be enhanced by a greater understanding of the cognitive, attitudinal and behavioural components of adaptability. The study described in this thesis will investigate the coping ability of career resilience that may relate to the attitudinal and cognitive components of adaptability. The career resilience construct may also provide better insight into the traits and abilities required to 40 cope with the different career concerns. The career status construct on the other hand may also elucidate the specific attitudes and strategies used by adults in the face of various career barriers. The current career status of an individual may be a codeterminant of saliency of career concerns with the particular career stage. A theoretical integration of social and environmental factors (career status) and coping skills (career resilience) with career concerns may clarify some of the questions regarding the vocational adjustment of adults. 2.5.5 Career salience The model of career salience is useful in the contemporary context as it allows for the fact that the career has relative importance in relation to other life roles. An adult’s level of commitment to, participation in and knowledge of a job determines the importance of the career to the person (Super, 1982). The relevant saliency of the worker role may be indicative as to why adults at times have career concerns that may not relate to the career stage. An individual may for instance make career decisions based on the greater importance of the homemaker role than the worker role. Super’s theory proves further useful in that it also accounts for the role of values in one’s career life. The model of career salience shows the role of values in the development and maintenance of the career attitudes and behaviours of a person. Thus Super accounts for other personal and situational influences on the importance of work in the career. 2.5.6 Career determinants Considering the rainbow model, the model of career maturity and adaptability and the model of work salience discussed above, it is evident that this career development theory accounts for affective, cognitive as well as behavioural factors in career choice and adjustment. Life roles, career stages, coping skills, attitudes, behaviours and cognitions all play an important role culminating in a career choice and affecting the way in which the adult adjusts to the changes in the world of work. A person is not merely seen as a victim of his age or career stage, but through his coping skills and adaptability he may plan, explore, gain information, make informed decisions and accurately assess the reality about 41 himself and his work situation. His commitment to his career, participation in work and knowledge of the job are all factors that are dependent on how important the worker role is to him, in relation to other roles such as that of leasurite or citizen. One may argue then that according to the model of determinants the background and demographics of a person’s life is of the least consequential importance in determining a person’s career and outcomes, although they form the foundation of all the other factors that affect the career. More importantly, a person’s personality and achievements and the employment practices provided by society equally influences the nature of a person’s reaction to career challenges. Of greater influence though than personality and society are the specific developmental stage of the person and his self-concept as a worker. As said above, all these factors are subject to the self as decision-maker. Up to this point of the evaluation it is evident that Super has created a comprehensive theory of careers. Evidently these models encompass most of the variables that have been associated with career choice and adjustment in research and literature. All these factors are also based by these models in vocational development theory. Over and above all these factors, the role of the self as agent in career choice and adjustment is recognised. Despite all internal and external vocational pressures, one can take control of one’s career destiny, but only within the boundaries presented by external and internal pressures. 2.5.7 The C-DAC model The heuristic value of the theory is illustrated by the C-DAC model, as it supplies the means for applying the theoretical models of the theory. As seen above, this model allows for the assessment of career concerns, interests, values and role salience in career counselling. The usefulness of this model can be improved by the inclusion of the assessment of adaptability and other career coping skills. 42 2.5.8 Summary Based on these models of Super’s theory one may summarise that the concept of career concerns is linked to both career stages and life roles as depicted by the rainbow model. Career concerns are further moderated by the absolute importance of the worker role as well as the relative salience of the role. One may argue that career concerns does not only relate to such stages and roles, but are further moderated by circumstantial, societal and personal factors in accordance with the model of career determinants. It seems that the level of career adaptability of an adult will help determine the content and extent of career concerns expressed. It seems however that as organisations and careers are changing in contemporary society, that adjustments need to be made in the theory to accommodate the reality of the changing world of work. 2.6 THE ADULT CAREER CONCERNS INVENTORY For the purpose of the present study emphasis is placed on one of the latest measures developed by Super. The Adult Career Concerns Inventory (Super et al., 1988) is only one of the many measures that operationalise the various facets of Super’s theory, and is primarily based on the concept of career adaptability. More specifically, the Adult Career Concerns Inventory operationally defines the planfulness component of adaptability (Savickas, 1997). 2.6.1 Description of the ACCI The 61-item Adult Career Concerns Inventory measures the concerns of the individual with career development tasks of the exploration, establishment, maintenance and disengagement stages and their substages. Respondents rate their level of concern with the developmental tasks ranging from ‘no concern’ to ‘great concern’ and also indicate on a single item whether career change is being considered or not (Rounds, 1994). According to Savickas, Passen and Jarjoura (1988) the Adult Career Concerns Inventory measures concerns with work-related development tasks or any vocational change in as far as these concerns depend on vocational development. The measure’s 43 scoring system allows both for ipsative and normative comparisons (Whiston, 1990). In addition to the above the final item of the instrument has been designed to identify concerns relating to recycling. The career status of the respondent, i.e. whether any career change is eminent or has recently occurred is obtained by this item (Super et al., 1988). The uses of this instrument include career counselling and planning for individuals, needs analyses in groups of employees, and research of possible correlations between adult career adaptability and psychological and socioeconomic variables. For counselling purposes test results may be interpreted ipsatively or normatively, but only if demographic data of the individual testee is considered. It may be used either for adults or adolescents at the point of entering an occupation (Super et al., 1988). The Adult Career Concerns Inventory may be used to assist individuals not only to identify exploratory needs, but also to detect the resources needed to cope with current career concerns (Niles, Anderson & Goodnough, 1998). It also provides information that may be used prior to career counselling (Rounds, 1994). 2.6.2 Research on the ACCI This discussion on the research on the Adult Career Concerns Inventory will focus only on the current Adult Career Concerns Inventory form in as far as its reliability and validity is concerned. The Adult Career Concerns Inventory manual primarily cites reliability coefficients of the earlier forms of the instrument, as well as research findings on the validity of the career adaptability construct in support of this measure. Brief mention is made of findings indicating a relationship between age and career stage-related concerns (Slocum & Cron, 1985), and relations between average age and age range and career stages (Cron & Slocum, 1986), as well as confirmation of the factor structure and appropriateness of the items of the earlier forms. According to Stout, Slocum and Cron (1987) the earlier form of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory has sufficient construct, concurrent and predictive validity. The manual however provides no evidence of test-retest reliability, nor of construct or concurrent validity of the current Adult Career Concerns Inventory form. 44 The manual reports only one validity study of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory apart from the normative analysis data. Mahoney’s (1986) unpublished doctoral dissertation revealed only weak relations between Adult Career Concerns Inventory scores and chronological age, suggesting that career concerns are not age-related. Job satisfaction moderated by age, was only moderately related to Adult Career Concerns Inventory scores. Career concerns and career satisfaction however were unrelated (Super et al., 1988), contrary to what may be theoretically expected. Savickas, Passen and Jarjoura (1988) measured the validity of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory concerns with tasks using as criteria measures of work adjustment and level of coping with tasks for a sample of salespeople. They found positive relations between task concerns (ACCI) and levels of task coping for exploration tasks. This applied since the difficulty in coping with tasks coincided with task concerns as well as difficulties with work adjustment. Halpin, Ralph and Halpin (1990) reported support for the construct validity as well as the reliability and the internal consistency of the five subtests of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory. Whiston (1990) found estimated reliability coefficients ranging from 0,76 to 0,95 and 0,81 to 0,96 for the Adult Career Concerns Inventory subscales. These coefficients reflect satisfactory internal consistency among the items of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory. The construct validity of the measure is also supported by means of factor analytical studies. The Adult Career Concerns Inventory manual accounts only for three factors, namely an Exploration factor, a merged Establishment and Maintenance factor and a Disengagement factor (Mahoney, 1986). The confounding of the Establishment and Maintenance stages was ascribed to the homogeneity of the age group (Super et al., 1988). Smart and Peterson’s (1994) factor analyses supported the hypothesised model of the stages (exploration, establishment, maintenance and disengagement) and career development tasks. Substantial cross-cultural support for the factorial structure of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory was found since the construct validity of the scale was supported both for North American and Australian samples. Smart and Peterson (1994) commented that the Adult Career Concerns Inventory is also sensitive to contemporary issues, such as delayed careers, recycling and second or third career options. 45 Duarte’s (1995) factor analysis of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory demonstrated the high internal consistency of its subscales. A principle components analysis revealed that the exploration and establishment subscales loaded on a single factor. This may be ascribed to the specific demographic data of the sample, instead of the inefficiency of the measure. Two distinct factors were however found for the maintenance and disengagement subscales. Niles, Lewis and Hartung (1997) studied the usefulness of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory in a revised behavioural format (ACCI-B) as opposed to the attitudinal format used in the present study. The revised format indicates actual task involvement and participation in career development tasks. Results supported the hypothesis that there is an inverse relationship between actual involvement with exploration stage tasks and mental concerns with the task. They concluded that task involvement may actually lessen task concerns. The researchers also found that task involvement according to the ACCI-B relates positively with vocational identity and negatively with a need for career information. Involvement with tasks relates positively with career choice and certainty and negatively with career indecision. In the manual, Super et al. (1988) recognise the need for further construct and predictive validation studies of the instrument. Construct validation studies may look at differences in terms of age and career stage, gender and occupations, whereas predictive validation studies could look at the role of career concerns in predicting success. A limitation of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory is that the norms for interpreting the data are based on a small sample, which also does not sufficiently represent the population younger than 23 or older than 59 (Rounds, 1994). The age group limitation however will not affect the proposed study. 46 2.6.3 Evaluation of the ACCI In evaluation of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory it should be noted that this instrument does not measure the completion of a developmental task (Whiston 1990) or levels of coping with the task (Savickas et al., 1988), but merely concern with a task as it is currently experienced by the testee. The Adult Career Concerns Inventory only evaluates the planfulness dimension of adult career adaptability, omitting the dimensions of time perspective, exploration (attitudes), information and decision-making (cognitive) and reality orientation (Niles et al., 1997). Further research is required to examine the relationship between expressed concerns and those revealed by Adult Career Concerns Inventory scores. The predictive validity of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory need to be enhanced by means of longitudinal studies. There is also a need for more representative norm groups acquired through studies using bigger samples and that are representative of different occupational, educational and gender groups (Whiston, 1990). A further limitation of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory is that it measures attitudes, and not behaviours, and does therefore not indicate actual reasons for the level of concern measured. Adult Career Concerns Inventory scores do not indicate whether a low concern for a task is due to it being inappropriate for a current career stage, or already successfully accomplished, or due to lack of involvement of the person (Niles et al., 1997). Conclusions drawn from a study by Savickas et al. (1988) include that career concerns is an ambiguous construct in as far as identical scores have different meanings. According to these researchers the career concerns construct does not indicate the degree of career development, since the Adult Career Concerns Inventory measures both developmental and adaptive tasks. A measured concern may indicate the need to develop or to adapt or to change. In summary, the greatest strengths of the Adult Career Concerns Inventory are that it is grounded in Super’s model and shows internal consistency. The Adult Career Concerns Inventory however needs more validation studies and better norms, and it can be criticised for the fact that research does not support the distinctiveness of the stages. 47 2.7 CONCLUSION Although the world of work has seen many changes over the past few decades, Super’s theory still provides a useful foundation for the understanding of vocational development in the contemporary context. However, in order to adequately describe vocational reality and enhance the utility of this theory, there is a need for the continuous evolution of the premises of the theory according to the example set by Super himself. Scholars and researchers need to constantly re-evaluate both the adequacy and heuristic value of this multifaceted approach to careers in order to keep pace with the current vocational changes. Of specific value to the study described in this thesis, is Super’s explication of the developmental tasks and various concerns that adults are challenged by in the course of their careers. The career concerns construct must be understood in terms of the life-career rainbow model’s stages. It has become apparent however in the preceding discussion and evaluations that the career stages might not be as stagnant and limited as portrayed in Super’s work. Apparently adults may harbour career concerns characteristic of any of the career stages and developmental tasks at any given time in their careers. Super et al.’s (1988) recycling concept is a possible, but incomplete, explanation for deviations from expected patterns in career development. As there is a persisting need for convergence in vocational psychology theories, and since it has been shown above that Super’s theory relates to many of the main frames of reference in vocational psychology, the career concerns construct should also be understood in relation with other important concepts and models in vocational psychology. In the next chapter the attitudes and strategies of adults in the face of such career concerns will be addressed, and in the following chapter adult career resilience as coping mechanism with such concerns will be expounded.