A Review of NDC Strategies for Tackling Low Demand and

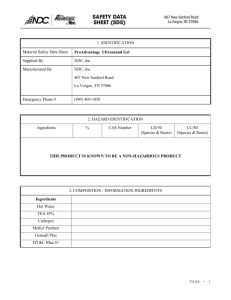

advertisement