Stylistic Variation and Roman Influence in the

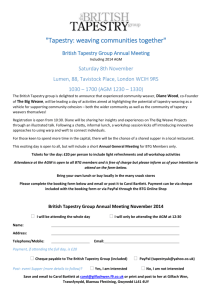

advertisement