women entrepreneurs style of transformational

advertisement

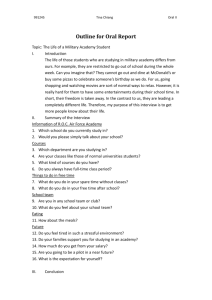

USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0062 WOMEN ENTREPRENEURS STYLE OF TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP AND PERFORMANCE OUTCOMES: AN INTERACTIVE APPROACH TO BUILDING A CLIMATE OF TRUST Dorothy Perrin Moore, Professor Emeritus, The Citadel 2857 Jasper Boulevard, Sullivan’s Island, SC 29482 Tel: 843-883-3089 E-mail: dot.moore@comcast.net Jamie L. Moore, Workforce Program Manager, Long Island Forum for Technology (LIFT) Jamie W. Moore, Professor Emeritus, The Citadel ABSTRACT The trust building, transformational leadership style developed by women to succeed in corporate environments, and which they further refine after making the transition to entrepreneurship, is well suited to dealing with operational challenges in turbulent economic environments. Women owner/managers create a climate of trust by using an interactive teamfocused style which, by encouraging open exchanges, collaborations and collective creativity, moves employees to the status of valued insiders and high performers. Suggested respondent groups and a sound methodology are provided for testing the propositions involved in the process. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This work suggests a number of propositions for testing that the leadership skills developed by women in corporate environments and later applied in building their own businesses enable them to deal successfully with the uncertainties of a down-turned economy. Each proposition is drawn from findings in entrepreneurship and organizational behavior; specifically, in the areas of building trust, applying transformational leadership, team building skills and perceptions of gender diversity. The first proposition presented in this study is basic. It consists of two elements. The first, that more than men, women employ an interactive and transformational leadership style, has long been noted in numerous studies. The second, that women managers honed this skill to move beyond the stereotypes associated with being an outsider in business environments, is derived from more recent findings that collectively overwhelm the non-evidentiary suggestions that women are genetically or culturally programmed to lead and manage this way. The second and third propositions are derived from findings that because trust is central to team performance and as the interactive style of leadership has a pronounced positive impact on performance outcomes, not only will the most successful entrepreneurs endeavor to create and maintain a climate of trust in their businesses, women entrepreneurs will be highly effective in doing this. The reasons are described in the next two propositions, both of which arise from a close examination of the trust literature; in particular, the factors that enable leaders to overcome the bias effects of stereotypes and insider/outsider conflicts common to organizational life. The USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0063 final proposition, that the female entrepreneur’s interactive, transformational leadership style positions her firm to deal effectively with the difficult economic climate through high employee performance, draws from literature in the fields of entrepreneurship and organizational behavior and is important to advancing our knowledge about company growth based on women’s interactive leadership style. Recommendations are presented for testing the propositions with a single or a series of empirical tests across a variety of respondent groups. INTRODUCTION Over the past several decades, the forces of rapid economic and technological change, the influx of women and minorities into the workforce, the economic shift to a post industrial, global economy, and an investment market emphasis on short term profits combined to reshape organizations. Major components of the change included organizational restructuring, the erosion of employee trust in organizations and their leaders, the emergence of work teams as drivers of firm performance, diversity and the rise of new styles of team leadership. Prior to the severe economic downturn that began in mid-2008, many women in organizations, who had mostly been confined to the lower and middle management levels, and in the majority of organizations denied any opportunity to move into upper management (Dencker, 2008), made the transition to private ownership (Bullough, Kroeck, Newburry, Lowe & Kundu, 2010). They took their experience and successful management style with them (Moore & Buttner, 1997; Moore, 2000, 2010a). According to recent figures, the some 10.1 million privately held businesses that are at least 50% woman-owned generated nearly $2 trillion in revenues and provided some 13 million jobs. The 7.2 million firms with at least 51% woman-ownership generated $1.1 trillion in revenues and provided 7.3 million jobs. Businesses operated by women of color make up slightly more than one fourth (26%) of this total and, at three times the rate for all start-ups, women of color constituted the fastest growing group of female entrepreneurs (Center for Women’s Business Research, 2008-2009). This work proposes to connect the important transitions women made as they exited the corporate environments where they had learned to practice an interactive style of managing and leading with findings in the fields of entrepreneurship, leadership, teamwork and trust to explore a management and leadership strategy employed by women who face a changed economic environment. The propositions are based on findings that trust, governance and team member relationships have mutual, complimentary effects (Puranam & Vanneste, 2009; Faems, Janssens, Madhok & Van Looy, 2008), that conceptualizations of trust – can I/should I trust this person? – vary widely (Bigley & Pearce, 1998) and that the style of leadership practiced by women owners, which has a pronounced impact on employer – employee interactions and performance outcomes (Karakowsky & Siegel, 1999), enhances trust and productivity in turbulent and difficult economic environments. We begin by first examining the entrepreneurial work environments women construct through their interactive transformational leadership styles to create a climate of trust that, in turn, enables employees to move from an external status to internal participant and contributor to firm effectiveness. We then examine the phenomenon of trust, including an array of views, violations and methods of repair (Moore, 2010b; Kim, Dirks & Cooper, 2009), the influential component of gender and diversity in trust building and the development of efficient, highly productive, teamcentered enterprises. We conclude by offering suggestions on how this model of the USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0064 entrepreneurial woman’s leadership style may be tested to establish an initial set of empirical findings to enhance our understanding of the interaction effects and outcomes in organizations owned by women. We especially propose that the relationships be tested in respondent groups of women who aspire to grow their businesses. BACKGROUND, DEVELOPMENT AND UNDERLYING PROPOSITIONS The Influence of the Organizational Setting on Women’s Leadership Style Prior to the most recent exit of women to business ownership, the organizational environment had become more turbulent. To deal with globalization and more intense competition, corporate managers employed the new information technologies to raise productivity, reduce layers of bureaucracy and trim the number of long term employees. By relying more heavily on well coordinated work teams, they achieved greater efficiency (Ilgen & Sheppard, 2001; Osterman, 2000). Teams produced results because, by utilizing the new information sharing technologies, people with differing backgrounds, information sets, resources, perspectives and problem solving approaches could be brought together to contribute to a collective creativity in environments real or virtual (Mannix & Neale, 2005). The use of teams quickly became an important determinant of organizational productivity (Salamon & Robinson, 2008). The best results were achieved when teams were built by assembling people with the skills needed and allowing them to operate in a culture that encouraged openness, knowledge sharing and empowerment (Brower, Schoorman & Tan, 2000; Davis, Schoorman, Mayer & Tan, 2000; Messick, 1999; Weber, Kopelman & Messick, 2004). For teams to function well, however, leaders had to employ a management style conducive to building a feeling of trust and the open exchange of information among people with diverse skills and backgrounds wherein individual expertise would be supported, utilized and appreciated (Kuo, 2004; Mannix & Neale, 2005: 4142). The difficulty was that the ongoing and widespread restructuring had eliminated many employee benefits and eroded trust. Queried in 2009, more than half of American workers said they did not trust their organization’s leaders and an even higher percentage felt their employer had violated their contractual relationship (Dirks, Lewicki & Zaheer, 2009). Further complicating the problems of leadership were the presence of biases inherent in organizational groupings that formerly had been homogenous (Mannix & Neale, 2005). What was needed was a management style that encouraged the creation and building of a culture of trust (Mills & Ungson, 2003) that enabled firms to deal with periods of uncertainly or the eruption of a business crisis (McKnight & Chervany, 2006). Interactive transformational leadership was the style employed by many of the women managers who were rising in the organizational ranks and moving into work roles traditionally occupied by men. The entry of large numbers of women into the workplace, the emergence of teams and the growing importance of successful team management had provided women with opportunities to showcase their leadership skills. But as a consequence of prevailing attitudes (Kossek, Market, & McHugh, 2003), including stereotypical negative behaviors (Kanter, 1997; Ely, 1995), the lack of role models and supportive relationships in organizations (Ely, 1994, p. 203; Liff & Ward, 2001), women often found themselves marginalized (Kanter, 1977) and denied access to power (Kanter 1987). Highly visible but isolated (Sealy, 2010), they learned from experience to employ an interactive style of transformational leadership because it could moderate the effects of gender biases (LePine, Hollenbeck, Ilgen, & Ellis, 2002). USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0065 The style in which women in corporate life and women entrepreneurs use transformational leadership in their own companies has been relatively unstudied, and to date little research has addressed the impact of women’s leadership styles in building trust among members of entrepreneurial teams within organizations. Finding in other settings, however, suggest that although evidence for sex differences in leadership is mixed and leadership styles depend upon context, in general, women tend to employ a transformational approach and are more likely than men to do so (Bycio, Hackett, & Allen, 1995; Bass, Avolio, & Atwater, 1996; Yammarino, Dubinsky, Comer & Jolson 1997; Moore & Buttner, 1997, Moore, 2000, 2010a). The body of research further suggests that women behave more democratically than men in leadership situations, use interactive skills, place emphasis on maintaining effective working relationships, and value cooperation and being responsible to others, practices that all serve to further organizational goals by achieving outcomes that address the concerns of all parties involved (Rosener, 1990, 1997; Moore & Buttner, 1997; Buttner, 2001; Moore, 2000, 2010a; Eagly & Carli, 2003; Eagly, Johannesen-Schmidt & van Engen, 2003). Placing great value on relationships and forging ties to each team member, women leaders move toward integrating people into the group as respected individuals (Yammarino, Dubinsky, Comer & Jolson 1997; Moore & Buttner, 1997). This form of interactive transformational leadership is especially applicable in organizational team settings where the construction of individually unique, one-toone, somewhat egalitarian interpersonal relationships is both appropriate and advantageous. Helgesen (1995) depicts this approach as a web. It may be visualized as the leader sitting at the center of a wheel, connecting directly to each team member or subordinate by a spoke, with these individuals linked to each other along the rim and the entire group involved in interactive communications (Moore, 2000). In this setting, irrespective of individual differences, every team member becomes an insider. There appear to be a number of related reasons why women lead this way. In organizations, many faced problems common to managers who were not insiders. Many in addition had to meet requirements more stringent than their male counterparts to attain a leadership role in the first place and once in a position of leadership had to act more skillfully to avoid backlash (Tharenou, 1999; Oakley, 2000). They thus brought to positions of leadership a repertoire of behaviors consistent with what people expect from women in order to ease the transition and acceptance into the group (Gupta, Turban, Wasti, & Sikdar, 2009) and avoid or lessen the negative reactions most had experienced from exerting authority, particularly over men, or displaying a too high level of competence or appearing to dominate (Eagly, Johannesen-Schmidt & van Engen, 2003: 572-574; van Engen, van der Leeden, & Willemsen, T., 2001; Madlock, 2008; Beasley, 2005). As entrepreneurs, women built on their organizational skills, employing an interactive (all minds are needed at the table) approach to both encourage creativity and balance the authoritative command-and-control behaviors expected of a male boss with the more collaborative language and communication styles expected of a woman leader (Moore, 2000: 100-106). Proposition 1: Women entrepreneurs employ an interactive and transformational leadership style to move beyond the stereotypes associated with being an outsider in business environments. The underlying rationale of Proposition 1, the emergence of the interactive, transformational style of women’s leadership, is depicted in Figure 1. USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0066 Approaches Used by Women Owners to Build Trust Transactions that foster venture innovation are frequently the result of collaborations that depend on open-mindedness, shared vision and mutual expectations of positive reciprocity (Van de Ven, Ring, Zaheer, & Bachman, 2006; Viklund & Sjöberg, 2008). Such transactions commonly arise from reciprocating patterns of trust that lead to inter-group trust and which may, in turn, spawn inter-organizational trust (Currall & Inkpen, 2006: 245). Within a business venture, then, trust “is as much a condition or ingredient as the outcome of action” (Sydow, 2006: 379). At the most basic level, trust is conveyed by an individual, the trustor. The trustee may be a group, a larger subset of the organization or the firm itself (Janowiez & Noorderhaven, 2006). Whether through the formal patterns of communication, coordination and decision making or informally, the interactions between trustor and trustee take place within the overlapping social, cultural, institutional, organizational and sub-organizational environments. Collectively, this is the organizational climate created by the everyday practices and reputations that leaders build and maintain over time (Moore, 2010b; Rhee & Valdez, 2009). The culture can either encourage or discourage trustworthy behavior (Whitener, Brodt, Korsgaard & Werner, 1998: 520), but when it contains “a high degree of taken-for-grantedness,” it will enable trust and “shared expectations,” even among employees “who have no mutual experience or history of interaction” (Möllering, 2006: 373). The observed benefits of a climate of trust – enhanced efficiency, greater productivity, decreased absenteeism, lower rates of employee turnover, better safety records, higher levels of commitment (Neves & Caetano, 2006) – contribute directly to firm value (Mayer & Gavin, 2005). This is especially true when a trust climate results in a sharing of knowledge among employees because the acquisition and utilization of knowledge, which “has the potential to be the source of extraordinary returns” (Madhok, 2006: 108), is a special, intangible economic asset (Casson & Giusta, 2006). Ideally, a company will employ systems designed to build this into a climate of collective trust. But this is not always the case, and even firms that try to create a culture of trust may accomplish the task only in varying degrees (Bezrukova, Jehn, Zanutto, & Thatcher, 2009, Moore, 2010b). USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0067 Proposition 2: Because trust is essential to firm performance and productivity, the most successful entrepreneurial leaders will employ an interactive leadership style to create and maintain a climate of trust. As noted earlier, of all the styles of leadership, the transformational style has the most significant positive impact on team performance (Kuo, 2004) because of its effects on moderating complex issues that could become contentious (Huettermann & Boerner, 2009), its multi-cultural and personal appeal to women (Fein, Tziner & Vasiliu, 2009), its encouragement of employee learning, creativity and implementation skills (Chiu, Lin & Chien, 2009), its ability to develop high quality leader-follower relationships (Carter, Jones-Farmer, Armenakis, Field & Svyantek, 2009) and the advantage it confers in building trust (Brahnam, Margavio, Hignite, Barrier & Chin, 2005). Proposition 3: The employment of a transformational leadership style by a woman entrepreneur will be perceived as highly effective in settings where interactions are sensitive and performance outcomes are highly valued. A Gendered Approach to Building Entrepreneurial Trust The number of studies isolating any effects of gender on productivity is slight (LePine, Hollenbeck, Ilgen, & Ellis, 2002), though there is at least one strong suggestion of an “overall positive linear relationship between gender diversity and employee productivity” (Ali, Kulik & Metz, 2009). The value of adding women members to teams has been supported in studies of IPO firms (Welbourne, Cycyota, & Ferrante, 2007), small firm performance (Litz & Folker, 2002), military settings (Hirschfeld, Jordan, Feild, Giles, & Armenakis, 2005) and, most recently, corporate boards (Konrad, Kramer & Erkut, 2008). Findings suggest that when the number of women increases to the point where they are no longer seen as token members, collaboration, solidarity, conflict resolution, reciprocity and self-sustaining action all rise (Westermann, Ashby, & Pretty, 2005; Piercy, Cravens, & Lane, 2001), as do work group effectiveness (Knouse & Dansby, 1999), levels of interpersonal sensitivity (Williams & Pollman, 2009) and innovation (Torchia, Calabro & Huse, 2010). Among the strongest suggestions favoring the business case for diversity is a longitudinal examination of 353 companies that remained on the Fortune 500 list for four years out of a five year span (1996-2000) that showed a strong correlation between significantly higher returns on equity (35%) and total returns to stockholders (34%) and the representation of women in senior management (Catalyst, 2004). Moreover, as Konrad, et al. (2008) has shown, with three or more women on corporate boards, the presence of women becomes normalized rather than stereotyped and leads to a higher level of firm performance and innovation (Nielsen & Huse, 2010; Torchia, Calabro & Huse, 2010). The small number of other studies indicates that the participation of women either leads to positive outcomes or shows no negative productivity effects (Kochan, Bezrukova, Ely, Jackson, Joshi, Jehn, Leonard, Levine, & Thomas 2003). The suggestion is that in organizations that include a number of women (more than 15%) on top management teams and/or on their corporate boards, male participants tend to exhibit higher levels of trust in female leaders than in organizations where women’s inclusion is less than 15%. Thus, Proposition 4: In firms led by women entrepreneurs practicing interactive transformational leadership, male employees will exhibit a high level of trust in their women owners. USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0068 Dealing with Gender and Other Stereotypes to Build Trust and Lead Establishing a climate of trust can be difficult, particularly when employees are responding to stereotypes rather than actual leader behavior. The existence of biases based on selfcategorization (we’re more comfortable among people like us) and similarity attraction (us versus them) in relatively or formerly homogeneous groups is indisputable. Men, in general, trust a new male team member more than a new female team member (Spector & Jones, 2004), view a new male leader as having better management skills than a new female leader (Karau, Elsaid, & Knight, 2009) and prefer a masculine mode of leader behavior (Butterfield & Powell, 2010; Johnson, Murphy, Zewdie & Reichard, 2008). Male and female employees alike often have strong opinions of the way leaders should talk, act and behave and employ gender stereotypes in evaluating leadership (Namok, Fuqua & Newman, 2009). As Butterfield and Powell (2010) note, the masculine mode of behavior represents power and the leadership dimensions most employees seek. Similar traits are associated with entrepreneurs (Gupta, Turban, Wasti & Sikdar, 2009; Moore, 2010a). Such in-group/out-group mindsets can create harmful fault lines, especially in situations where success depends on collaboration and the sharing of knowledge (Gratton, Voigt & Erickson, 2007). For women leaders to be perceived as effective, they must surmount the double bind of needing to demonstrate both strength and sensitivity. The potentially negative effects of stereotyped behavior can be counteracted through diversity in expertise and the positive relationship with performance and organizational effectiveness, however (Mannix & Neale, 2005: 41-42). The presence of diversity within organizations suggests both positive and negative organizational outcomes (Jackson, Joshi & Erhardt, 2003; Svyantek & Bott, 2004) and skilled leadership is required to bring people together to accomplish an organizational task. Establishing and maintaining a climate of trust is critical. Negative or inconsistent leader behaviors or too close supervision can break an established trust chain. Even if a leader violates expectations only once, the incident can cause “a significant drop in the level of trust and make followers more sensitive to future actions” (Dirks, 2006: 24). In corporate life and entrepreneurship, women have fewer margins for error (Caleo & Heilman, 2009). For these reasons, women in positions of leadership tend to relate to individuals through a group-focused leadership style that facilitates identification and collective efficacy (Wu, Tsui & Kinicki, 2010). They do this because reaching an outcome of cooperative interdependence, the belief that we gain when others succeed (Williams, 2001), requires a uniform and equitable treatment that employees recognize and to which they respond. Proposition 5: The most effective tool for building and maintaining organizational trust is in applying the transformational leadership process in a manner that employees perceive as equitable. Trust, Team Building and Firm Related Outcomes Work dynamics occur within distinct, overlapping environments. They include the norms, values and beliefs of society at large; the culture and background of each individual; the expertise derived from education, experience, specialization and proficiency; and the views, insights, suggestions and opinions of family, friends and trusted others. In organizations and small businesses alike, these norms and values are continually referenced by members within their distinct work environments and the organizational and sub organizational units within which the interactions occur. As studies have shown, the approach that leads to higher USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0069 performance consists of engineering the best possible work climate through balancing the controls available to management with behaviors that encourage trust (Mills & Ungson, 2003; Long & Sitkin, 2006; Nooteboom, 2006; Schoorman, Mayer & Davis, 2007). Key factors that drive perceptions of trustworthy behavior include the degree to which the leader acts with integrity, demonstrates openness, takes an interest and displays confidence in people, acts as coach and advocate, and shares clear expectations about performance outcomes. Research further notes that because individual perceptions of the leader or owner’s abilities and trustworthiness differ from self-perceptions, it is critical for the leader/entrepreneur to recognize the differences between the extension of trust and how it is monitored. When the cumulative result of the leader/owner actions and individual responses is the creation of an atmosphere of reciprocity – the expectation that acts of trust will be repaid – the potential for mutual trustworthiness and higher productivity is maximized (Clark & Payne, 2006; Ferrin, Bligh & Kohles, 2007). As Rosener (1990) notes, women “are far more likely than men to describe themselves as transforming subordinates' self-interest into concern for the whole organization.” A female team leader in organizations is therefore likely to view her position in terms of supporting team members to assist in reaching their performance goals and go about this by employing a participative leadership style (Paris, Howell, Dorfman, & Hanges, 2009) that ultimately results in leading in a different way (Nielsen and Huse, 2010). With effective communication as perhaps her most important leadership skill (Madlock, 2008), she will focus on the sharing of power and information and other positive individual relationships to create a collaborative team environment (Keeffe, Darling & Natesan, 2008; Moore & Buttner, 1997; Moore, 2000, 2010a). As entrepreneurs, women take similar initiatives critical to the creation of a climate of trust. Construction of a trust climate involves many elements: each employee’s personal propensity to trust, their past experiences and, based on continuous observations of owner’s behavior and information shared among workers, individual perceptions of the owner as an advocate who will reciprocate trustworthy behaviors (Drath, McCauley, Palus, Van Velsor, O'Connor & McGuire, 2008). The woman business owner tends to be continually cognizant of her actions and the ramifications of practices and behaviors that impact employees because she knows it is through their experiences that they perceive the firm’s overall fairness (Brockner, Fishman, Reb, Goldman, Spiegel, & Garden, 2007). As Morrison & Robinson (1997) describe, the result is likely to be better performance outcomes because in a high trust climate people show increased levels of loyalty, satisfaction and engagement and the resulting cooperation and free exchange of information leads to quicker and better decisions. By contrast are the negative outcomes often observed in a low-trust climate: delayed decisions, absenteeism, lost productivity, missed goals, upset customers, stagnant growth, and groupthink, along with such counterproductive behaviors remaining in the organization for a paycheck despite disgruntlement or focusing on “managing up” – often telling superiors what they want to hear instead of what they need to know – rather than concentrating on ways to increase organizational productivity and efficiency. For a business owner, the reasons to proceed in a trustworthy fashion are compelling. Proposition 6: The application of the interactive, transformational leadership style as a tool to create a climate of trust will enhance the longevity of women owned firms through higher employee performance. USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0070 Figure 2 presents the relationship of the team building moderators described in Propositions 2 through 6 to the suggested effectiveness outcomes. SUMMARY, THEORETICAL IMPLICATIONS AND TESTS The propositions presented here are drawn from empirical and theoretical research in the areas of entrepreneurship, organizational behavior and management and specifically focus on findings extrapolated from research in leadership, teamwork, trust, gender and diversity. The propositions presented in Figure 2 depict the relationships between building trust to enhance entrepreneurial firm effectiveness by employing an interactive transformational leadership style (the predictor variable). Relationships are drawn from the literature to suggest a fresh approach to understanding how the modern entrepreneurial woman leader creates a climate of trust and empowerment in team building (moderator variables) leading to the outcome variables of open communications, employee satisfaction, innovation and enhanced productivity that both provide greater financial returns and strengthen the firms position in today’s dynamic and rapidly changing markets. The present research moves beyond past findings on how women and men apply transformational leadership to enhance performance to suggest an underlying rationale of why doing so is important for women entrepreneurs and the economy at large. The contribution of this set of propositions is that, by highlighting the relationships between trustor and trustee, it suggests that engagement over time and prior experience with women as the norm in organizations creates an open environment that avoids the negative effects of gender stereotyping and enables women to use a more interactive and inclusive leadership approach to improve firm performance. The propositions may be tested with a single or with a series of empirical tests across a variety of respondent groups. To advance our knowledge on the way women entrepreneurs use the transformational interactive leadership process to create and build a climate of trust, it will be important to draw respondents from ventures at threshold stages of growth who have focused on empowering teams for company development and who have worked to create the climate of trust described here. USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0071 To test the proposed relationships, it will be important to identify women entrepreneurs whose firms are sufficiently large. Some of these firms may be in that group identified by the Center for Women as being part of the “missing middle;” i.e., as defined by Julie Weeks (Womenable) as those “who own established enterprises, yet who have not grown their firms to substantial levels of revenue or employment.” Other respondent groups may be among those firms with 25 or more employees who have reached various threshold stages and whose owners are interested in growing their businesses. Still other respondent groups will be found across the small business and entrepreneurial sector, including those engaged in the international market, technology and manufacturing, as well as the service industries. This last group, according to research from the Diana Project (Holmquist & Carter, 2009), clearly demonstrates the positive potential of female entrepreneurship. The propositions clearly are not designed to be tested on nascent entrepreneurial groups as the woman entrepreneur’s latitude of leadership would not be sufficiently extensive to test the proposed relationships. Another possible research avenue is to test cross gender effects by drawing the respondents from those organizations with mixed sex leadership or equivalent ownership in the firm in copreneurial enterprises. Godwin, Stevens, & Brenner (2006), for example, theorize that mixed gender leadership in firms in male-dominated sectors of the economy may enhance legitimacy and enable access to a larger number of resources and a stronger, more diverse social network. Relationships can be tested by drawing measures of the various relationships on work teams using current valid instruments for studying the organizational climate, trust and repair approaches (Kim, Dirks & Cooper, 2009; Gillespie & Dietz, 2009) as well as stereotypes and attitudes toward women entrepreneurs (Namok, Fuqua & Newman, 2009) and managers (Zeynep & Soner, 2010). Evidence of the employment of the transformational interactive approach by women entrepreneurs (Moore & Buttner, 1997), along with variations of the Transformational Leadership Inventory (TLI) and productivity scales that measure the end predictor results of the transformational style on work teams, can be combined with a trust index inventory. See Palrecha (2009) for a number of specific scales and tools with reliability and validity. The approach may be enhanced by adding other links to the propositions. For example, Kim, Dirks & Cooper (2009) propose three levels of trust repair that could be included to enhance the understanding of the broad range of trustor-trustee building influences and other potential interactions. Attributions in trust repair that add another possible dimension in building effective work teams (Tomlinson & Mayer, 2009) are also applicable, as are expectations (Möllering, 2005) and the instruments developed by Konrad, Kramer, & Erkut (2008) and Huse & Solberg (2006) to measure the impact of the number of women in leadership positions on innovation and productivity. The cumulative nature of the propositions presented here is not only important in understanding the emergence of present organizational cultures in women owned businesses, leadership approaches and tools needed to build trust; it suggests a gender blind approach to develop strategies effective in the current economic environment to get people back to work. Bringing the knowledge gained by women in predominantly male environments which enables them to use transformational leadership to bear on current problems is more than integrative; it points to a fresh approach to building and repairing relationships in teams of diverse members. It has often been said that research on gender has a limited number of theoretical underpinnings for building models. Not so. When considering the pool of theories from various fields of research USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0072 that collectively take the actions of women into account, a number of robust propositions emerge. Some are presented here. Hopefully, this will encourage other conceptualizations that go beyond descriptions of the interactive style of transformational leadership and management practiced by women to suggest new universal management practices and the important economic role of women owners. REFERENCES Ali, M., Kulik, C. T., & Metz, I. 2009. The impact of gender diversity on performance in services and manufacturing organizations. Paper presented at the Academy of Management, Chicago. Bass, B. 1990. From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organizational Dynamics, 18: 19-31. Beasley A. L. The Style Split. Journal of Accountancy [serial online]. September 2005, 200(3): 91-92. Available from: Business Source Premier, Ipswich, MA. Accessed December 15, 2009. Bezrukova, K., Jehn, K. A., Zanutto, E. L., & Thatcher, S. M. B. 2009. Do workgroup faultlines help or hurt? A moderated model of faultlines, team identification, and group performance. Organization Science, 20(1): 35-50. Bigley, G. A., & Pearce, J. L. 1998. Straining for shared meaning in organization science: Problems of trust and distrust. Academy of Management Review, 23: 405-421. Brahnam, S. D., Margavio, T. M., Hignite, M. A., Barrier, T. B., & Chin, J. M. 2005. A genderbased categorization for conflict resolution. Journal of Management Development, 24: 197-208. Brockner, J., Fishman, A. Y., Reb, J., Goldman, B., Spiegel, S., & Garden, C. 2007. Procedural fairness, outcome favorability, and judgments of an authority's responsibility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92: 1657-1671. Brower, H. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Tan, H. 2000. A model of relational leadership: The integration of trust and leader-member exchange. Leadership Quarterly, 11: 227-250. Bullough, A., Kroeck, K. G., Newburry, W., Lowe, K. B., & Kundu, S. K. 2010. Women’s participation in leadership around the globe: An institutional analysis. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Montreal. Butterfield, D. A., & Powell, G. N., 2010. Should Sarah and Hillary run again? Gender and leadership in the 2008 U.S. presidential elections. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Montreal. Buttner, E. H. 2001. Examining Female Entrepreneurs' Management Style: An Application of a Relational Frame. Journal of Business Ethics, 29(3): 253-269. Bycio, P., Hackett, R. D., Allen, J. S. 1995. Further assessments of Bass's (1985) conceptualization of transactional and transformational leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80: 468-478. USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0073 Caleo, S., & Heilman, M. E. 2009. Differential reactions to men and women's interpersonal unfairness. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Chicago. Carter, M. Z., Jones-Farmer, A., Armenakis, A. A., Field, H. S., & Svyantek, D. J. 2009. Transformational leadership and followers’ performance: Joint mediating effects of leader-member exchange and interactional justice. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Chicago. Casson, M., & Giusta, M. D. 2006. The economics of trust. In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research: 332-354. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar. Catalyst. 2004. Catalyst Study Reveals Financial Performance is Higher for Companies with More Women at the Top. (Released News Report: http://www.catalyst.org 1.26.04). Chiu, C. Y., Lin, H. C., & Chien, S. H. 2009. Transformation leadership and team behavioral integration: The mediating role of team learning. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Chicago. Clark, M. C., & Payne, R. L. 2006. Character-based determinants of trust in leaders. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 26(5): 1161-1173. Cleveland, J. N., Stockdale, M., & Murphy K. R. 2000. Women and men in organizations: Sex and gender issues at work. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Currall, S. C., & Inkpen, A. C. 2006. On the complexity of organizational trust: a multi-level co-evolutionary perspective and guidelines for future research. In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research: 235-246. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar. Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., & Tan, H. H. 2000. The trusted general manager and business unit performance: Empirical evidence of a competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 21: 563-576. Dencker, J. C. 2008. Corporate restructuring and sex differences in managerial promotion. American Sociological Review, 73: 455-476. Dirks, K. T., Lewicki, R. L., & Zaheer, A. 2009. Repairing relationships within and between organizations: Building a conceptual foundation. Academy of Management Review, 34: 68-84. Dirks, K. T. 2006. Three fundamental questions regarding trust in leaders. In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research: 15-28 @ p. 24. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar. Drath W., McCauley C., Palus C., Van Velsor E., O'Connor P., & McGuire, J. Direction, alignment, commitment: Toward a more integrative ontology of leadership. Leadership Quarterly [serial online]. December 2008: 19(6): 635-653. Available from: Business Source Premier, Ipswich, MA. Accessed December 15, 2009. Eagly, A. H., Johannesen-Schmidt, M. C., & van Engen, M. L. 2003. Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles: A meta-analysis comparing women and USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0074 men. Psychological Bulletin, [serial online]. July 2003: 129(4): 569-592. Available from: Business Source Premier, Ipswich, MA. Accessed December 15, 2009. Eagly, A. H., & Carli, L. L. 2003. The female leadership advantage: An evaluation of the evidence. Leadership Quarterly, 14: 807-835. Ely, R. J. 1994. The effects of organizational demographics and social identity on relationships among professional women. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39: 203-238. Ely, R. J. 1995. The power of demography: Women’s social constructions of gender identity at work. Academy of Management Journal. 38: 589-634. Faems, D., Janssens, M., Madhok, A., & Van Looy, B. 2008. Toward an integrative perspective on alliance governance: Connecting contract design, trust dynamics, and contract application. Academy of Management Journal, 51: 1053-1078. Fein, E. C., Tziner, A., & Vasiliu, C. 2009. Gender and age cohort effects on preferences for leadership behaviors: A study of Romanian managers. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Chicago. Ferrin, D. L., Bligh, M., & Kohles, J. 2007. Can I trust you to trust me? A theory of trust, monitoring, and cooperation in interpersonal and intergroup relationships. Group & Organization Management, 32: 465-499. Gillespie, N., & Dietz, G. 2009. Trust repair after an organization-level failure. Academy of Management Review, 34: 127-145 @ p. 127. Godwin, L. N., Stevens, C. E., & Brenner, N. L. 2006. Forced to play by the rules? Theorizing how mixed-sex founding teams benefit women entrepreneurs in male-dominated contexts. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, Sep2006, 30: 623-642. Gratton, L., Voigt, A., & Erickson, T. 2007. Bridging faultlines in diverse teams. MIT Sloan Management Review, 48: 22-29. Gupta, V. K.; Turban, D. B.; Wasti, S. A., & Sikdar, A. (2009). The role of gender stereotypes in perceptions of entrepreneurs and intentions to become an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 33: 397-417. Helgesen, S. 1995. The web of inclusion. New York: Currency Doubleday. Hirschfeld, R. R., Jordan, M. H., Feild, H. S., Giles, W. F., & Armenakis, A. A. 2005. Teams' female representation and perceived potency as inputs to team outcomes in a predominantly male field setting. Personnel Psychology, 58: 893-924. Holmquist, C., & Carter, S. 2009. The Diana Project: Pioneering women studying pioneering women. Small Business Economics, 32: 121-128. Huettermann, H., & Boerner, S. 2009. Functional diversity and team innovation: the moderating role of transformational leadership. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Chicago. Huse, M., & Solberg, A. G. 2006. Gender-related boardroom dynamics – How Scandinavian women make and can make contributions on corporate boards. Women in Management Review, 21: 113-130. USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0075 Ilgen, D. R., & Sheppard, L. 2001. Motivation in teams. In M. Erez, U. Kleinbeck, & H. Thierry (Eds.), Work motivation in the context of a globalizing economy: 169–179. New York: Erlbaum. Jackson, S. E., Joshi, A., & Erhardt, N. L. 2003. Recent research on team and organizational diversity: SWOT analysis and implications. Journal of Management, 29: 801-831. Janowiez, M., & Noorderhaven, N. 2006. Levels of inter-organizational trust: conceptualization and measurement. In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research: 264-279. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar. Johnson, S. K., Murphy, S. E., Zewdie, S. & Reichard, R. J. 2008. The strong, sensitive type: Effects of gender stereotypes and leadership prototypes on the evaluation of male and female leaders. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 106(1): 39-60. Kanter, R. M. 1977. Some effects of proportion on group life: Skewed sex ratios and responses to token women. American Journal of Sociology, 82: 965-990. Kanter, R. M. 1983. The Change Masters How People and Companies Succeed in the New Corporate Era. National Association of Bank Women Journal, 59: 4. Karakowsky, L., & Siegel, J. P. 1999. The effects of proportional representation and gender orientation of the task on emergent leadership behavior in mixed-gender work groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84: 620-631. Karau, S. J., Elsaid, (Abdel Moneim), M. K, & Knight, M. B. 2009. Managers: Comparing Egypt and the United States, Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Chicago. Keeffe, M. J., Darling, J.R., Natesan, N. C. 2008. Effective 360° management enhancement: the role of style in developing a leadership team. Organization Development Journal, 26: 89-107. Kim, P. H., Dirks, K. T., & Cooper, C. D. 2009. The repair of trust: A dynamic bi-lateral perspective and multi-level conceptualization, Academy of Management Review, 34: 401-422. Knouse, S. B., & Dansby, M. R. 1999. Percentage of work-group diversity and work-group effectiveness. Journal of Psychology, 133: 486 Kochan, T., Bezrukova, K., Ely, R., Jackson, S., Joshi, A., Jehn, K., Leonard, J., Levine, D., & Thomas, D. (2003). The effects of diversity on business performance: Report of the diversity research network. Human Resource Management, 42, 3–21. Konrad, A. M., Kramer, V. & Erkut, S. 2008. Critical mass: The impact of three or more women on corporate boards. Organizational Dynamics, 37: 145-164. Kossek, E. E., Market, K. S. & McHugh, P. P. 2003. Increasing diversity as an HRM change strategy. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16: 328. Kuo, C. C. 2004. Research on Impacts of Team Leadership on Team Effectiveness. Journal of American Academy of Business, 5: 266-277. USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0076 LePine, J. A., Hollenbeck, J. R., Ilgen, D. R., & Ellis, A. 2002. Gender composition, situational strength, and team decision-making accuracy: A criterion decomposition approach. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 88(1): 445-475. Liff, S., & Ward, K. 2001. Distorted views through the glass ceiling: The construction of women’s understandings of promotion and senior management positions. Gender, Work and Organization, 8(1): 9-36. Litz, R. A., & Folker, C. A. 2002. When he and she sell seashells: exploring the relationship between management team gender-balance and small firm performance. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 7: 341-359. Long, C. P., & Sitkin, S. B. 2006. Trust in the balance: How managers integrate trust-building and task control. In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA, 87-106. McKnight, D. H., & Chervany, N. L. 2006. An experimental study of trust in collective entities. In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research: 29-51 @ 29. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA. Madhok, A. 2006. Opportunism, trust and knowledge: The management of firm value and the value of firm management. In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research: 1-7-123 @ p. 108. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA. Madlock, P. E. 2008. The link between leadership style, communicator competence, and employee satisfaction. Journal of Business Communication, 45: 61-78. Mannix, E., & Neale, M. A. 2005. What differences make a difference? The promise and reality of diverse teams in organizations. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 6: 31-55. Mayer, R. C., & Gavin, M. B. 2005. Trust in management and performance: Who minds the shop while the employees watch the boss? Academy of Management Journal, 48: 874– 888. Messick, D. M. 1999. Alternative logics for decision making in social settings. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 38: 11-28. Mills, P. K., & Ungson, G. R. 2003. Reassessing the limits of structural empowerment: Organizational constitution and trust as controls. Academy of Management Review, 28: 143-153. Möllering, G. 2006. Trust, institutions, agency: towards a neoinstitutional theory of trust. In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research: 355-376. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA. Möllering, G. 2005. The Trust/Control Duality an Integrative Perspective on Positive Expectations of Others. International Sociology [serial online]. September 2005; 20(3):283-305. Available from: Business Source Premier, Ipswich, MA. Accessed December 15, 2009. USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0077 Moore, D. P. 2010a. Women as Entrepreneurs and Business Owners. In Karen O’Connor, Editor, Gender and Women’s Leadership: A Reference Handbook: 443-451. Thousand Oaks, CA. Sage. Moore, D. P. 2000. Careerpreneurs: Lessons from leading women entrepreneurs on building a career without boundaries. Palo Alto, CA. Davies-Black Publishing. Moore, D. P., & Buttner E. H. 1997. Women entrepreneurs: Moving beyond the glass ceiling. Thousand Oaks, CA. Sage. Moore, D. P. 1984. Evaluating in-role and out-of-role performers. Academy of Management Journal, 27: 603-618. Moore, J. L. 2010b. Building a climate of trust. In E. M. Mone & M. London (Eds.), Employee Engagement Through Effective Performance Management: 31-66. UK. Taylor & Francis Ltd. Routledge Academic Press. Morrison, E. W., & Robinson, S. L. 1997. When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. Academy of Management Review, 22: 226– 256. Namok, C., Fuqua, D. R. & Newman, J. L. 2009. Exploratory and confirmatory studies of the structure of the bem sex role inventory short form with two divergent samples. Educational & Psychological Measurement, 69 (4): 696-705. Nielsen, S., & Huse, M. 2010. Women directors’ contribution to board decision-making and strategic involvement: The role of equality perception. European Management Review, 7: 16-29. Neves, P., & Caetano, A. 2006. Social exchange processes in organizational change: The roles of trust and control. Journal of Change Management, 6: 351-364. Nooteboom, B. 2006. Forms, sources and processes of trust, In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research: 247-263. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA. Oakley, J. G. 2000. Gender-based barriers to senior management positions: understanding the scarcity of female CEOs. Journal of Business Ethics [serial online]. October 2, 2000; 27(4):321-334. Available from: Business Source Premier, Ipswich, MA. Accessed December 15, 2009.27: 321-334. Osterman, P. 2000. Work reorganization in an era of restructuring: trends in diffusion and effects on employee welfare. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 53(2): 179-196. Palrecha, R. 2009. Leadership—universal or culturally—contingent—a multi—theory/multi— method test in India. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Chicago. Paris, L. D., Howell, J. P., Dorfman, P. W., & Hanges, P. J. 2009. Preferred leadership prototypes of male and female leaders in 27 countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(8): 1396-1405. USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0078 Piercy, N. F., Cravens, D. W., & Lane, N. 2001. Sales manager behavior control strategy and its consequences: The impact of gender differences. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 21: 39-49. Puranam, P., & Vanneste, B. S. 2009. Trust and governance: Untangling a tangled web. Academy of Management Review, 34: 11-31. Rhee, M., & Valdez, M. E. 2009. Contextual factors surrounding reputation damage with potential implications for reputation repair. Academy of Management Review, 34: 146168. Rosener, J. B. 1990. Ways women lead. Harvard Business Review, 68(6): 119-125. Rosener, J. B. 1997. America's competitive secret: Women managers. Oxford University Press, UK. Salamon, S. D., & Robinson, S. L. 2008. Trust that builds: The impact of collective felt trust on organizational performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93: 593-601. Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H., 2007. An integrative model of organizational trust: Past, present, and future. Academy of Management Review, 32: 344-354. Sealy, R. H. V. 2010. Do the numbers matter? How senior women experience extreme genderimbalanced work environments, Paper presented at the Academy of Management, Montreal. Spector, M. D., & Jones, G. E. 2004. Trust in the workplace: Factors affecting trust formation between team members, The Journal of Social Psychology 144: 311-321. Svyantek, D. J., & Bott, J. 2004. Received wisdom and the relationship between diversity and organizational performance. Organizational Analysis, 12(3): 295-317. Sydow, J. 2006. How can systems trust systems? In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research: 377-392. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar. Tharenou, P. 1999. Gender differences in advancing to the top. International Journal of Management Reviews, 1: 11-33. Tomlinson, E. C. & Mayer, R. C. 2009. The role of causal attribution dimensions in trust repair. Academy of Management Review, 34: 85-104. Torchia, M., Calabro, A., & Huse, M. 2010. Critical mass theory, board strategic tasks and firm innovation: How do women directors contribute? Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Montreal. Van de Ven, A., Ring, P., Zaheer A., & Bachman, R. 2006. Relying on Trust in Cooperative Inter-Organizational Relationships, In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of trust research: 144-164. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA. van Engen, M., van der Leeden, R., & Willemsen, T. 2001. Gender, context and leadership styles: A field study. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology [serial online]. December 2001:74(5):581-598. Available from: Business Source Premier, Ipswich, MA. Accessed December 15, 2009. USASBE_2011_Proceedings-Page0079 Viklund, M., & Sjöberg, L. 2008. An expectancy-value approach to determinants of trust. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38: 294-313. Weber J. M., Kopelman, S. A., & Messick, D.M. 2004. Conceptual review of decision making in social dilemmas: Applying logic of appropriateness. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8: 281-307. Welbourne, T. M., Cycyota, C. S., & Ferrante, C. 2007. Wall Street reaction to women in IPOS: An examination of gender diversity in top management teams. Group & Organization Management, 32: 524-547. Westermann, O., Ashby, J., & Pretty, J. 2005. Gender and social capital: The importance of gender differences for the maturity and effectiveness of natural resource management groups. World Development, 33: 1783-1799. Whitener, E. M., Brodt, S. E., Korsgaard, M. A., & Werner, J. M. 1998. Managers as initiators of trust: An exchange relationship framework for understanding managerial behavior. Academy of Management Review, 23: 513-530. Williams, M., 2001. In whom we trust: Group membership as an affective context for trust development. Academy of Management Review, 26: 377–396. Williams, M., & Polman, E. 2009. Where colleagues fear to tread: How gender composition influences interpersonally sensitive behavior. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Chicago. Wu, J. B., Tsui, A.S., & Kinicki, A. J. 2010. Consequences of differentiated leadership in groups, Academy of Management Journal forthcoming number 1: 1-41. Retrieved 12.21.09 from: http://journals.aomonline.org/InPress/pdf/done/534.pdf Yammarino, F. J., Dubinsky, A. J., Comer, L. B., & Jolson, M. A. 1997. Women and transformational and contingent reward leadership: A multiple-levels-of-analysis perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 40: 205-222. Zeynep A., & Soner D. 2010. Attitudes towards women managers: development and validation of a new measure. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Montreal.