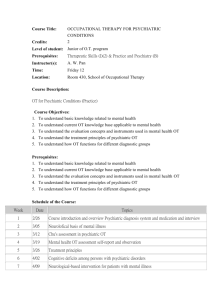

full text - Research Repository

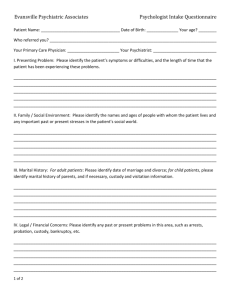

advertisement