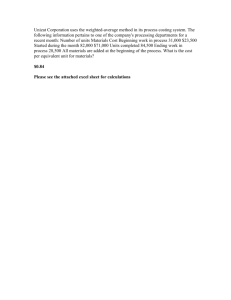

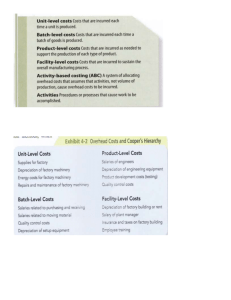

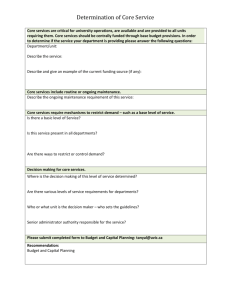

Cost Allocation and Activity-Based Costing

advertisement