Child and Adolescent Development Resource Book

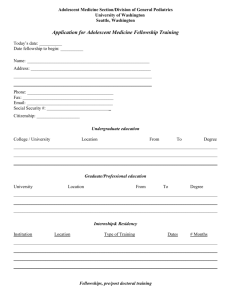

advertisement