The Cautionary Tale of Carolina Maria de Jesus

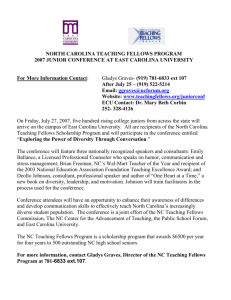

advertisement