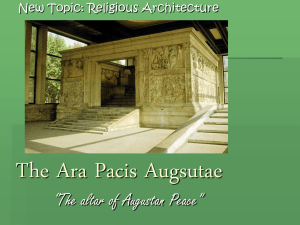

The 'Ara Pacis Augustae' J. M. C. Toynbee The Journal of Roman

advertisement

The 'Ara Pacis Augustae' J. M. C. Toynbee The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 51, Parts 1 and 2. (1961), pp. 153-156. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0075-4358%281961%2951%3C153%3AT%27PA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Z The Journal of Roman Studies is currently published by Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/sprs.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. http://www.jstor.org Mon Nov 12 07:47:44 2007 THE ' ARA PACIS A U G U S T A E ' By J. M. C. TOYNBEE Dr. Stefan Weinstock's article ' Pax and the " Ara Pacis " ', contributed to Volume L, 1960, of this Journal (pp. 44-58), has performed two signal services to archaeology. I n Part I of his paper the writer has given us a full and very valuable account of the cult of Peace in the Greek and Roman worlds from the fourth century B.C. to the Flavian age ; and throughout the study as a whole he most properly insists that we possess no explicit evidence, such as that of an inscription, to prove that the well-known monument excavated in the Campus Martius is to be identified with the Ara Pacis of the texts. This is a point on which all previous students of the monument, myself included, have certainly laid far too little emphasis. I t is, however, not perhaps quite fair to imply that the advocates of the equation have been victims of credulity (p. 44), even if they have in their writings taken that equation too much for granted, or to state that ' the question has never been asked why it [the monument] should be the Ara Pacis '. That question has, of course, been in everybody's mind and the answer to it has been given many times :-the building was undoubtedly a monumental altar of Augustan date ; it stood, where we learn from the records that the Ara Pacis stood, in the Campus Martius ; we have no allusion in literature or in epigraphy to any other Augustan altar, or, indeed, to any other Augustan building, in the Campus Martius that would tally with the evidence of the excavated edifice-an edifice so significant that the best available Greek craftsmen-almost certainly from Pergamon-were summoned to Rome to execute its marble carving ; and this sculptural decoration, a carefully thought-out unity, most faithfully reflects the whole ideology which we know from some Augustan literature and from some inscriptions to have lain behind the cult of Pax Augusta. Obviously this answer does not amount to complete proof ; but it surely justifies a rational belief that the Ara Pacis has in fact been found. At any rate, the burden of disproof has been shouldered by Dr. Weinstock ; and the question now is-has he proved clinchingly that the Ara Pacis has not yet been found ? First some comments may be made on the closing paragraphs of Part I of Dr. Weinstock's paper. On p. 51 it is stated that in A.D. 66 ' the Arvals offered sacrifice ob laurum [imperatoris Neronis] to Pax at the Arch of Ianus Geminus ' ; that ' this must have been done by Nero himself ' ; and that ' if an as issued in Gaul, perhaps at Lugdunum, shows an altar with the legend " Ara Pacis ", the natural inference would be that Nero built an -4ra Pacis, probably near the temple of Ianus where he performed his sacrifice in 66 '. But all this cannot be certainly deduced from the version of AFA LXXXI,85 printed by Dr. Weinstock in footnote 85 :-. . . Paci vacc(am) ante arcum [Iani Gemini] . . . For how do we know that the words ante arcum did not go with some sacrifice described in the lacuna after them ? In the same text, just above, the place, in Capitolio, precedes the names of the recipients of the sacrifice, there the Capitoline Triad ; just as in AFA XLII (A.D.38) the words in campo precede a d arum Pacis Augusta[e uaclcam immolavit (see p. 50, note 74). And in fact the words a d arcum have been taken to refer to some rite that was cited in the lacuna after them by Krister Hanell in his recent paper ' Das Opfer des Augustus an der Ara Pacis ' (Opuscula Romana 11, 1960, 99). Again, why should we infer that because Vespasian built the Templum Pacis in the region of Augustus' Forum ' the Augustan Ara Pacis [in the Campus Martius] no longer existed ' (p. 51) ? Why should not Pax have been provided with more than one cult-centre in the capital ? We turn now to Part 11, to Dr. Weinstock's discussion of our monument under six points. ( I ) On p. 53 it is asserted that ' neither is Pax represented on her altar nor her symbol, the caduceus, nor is her name inscribed on it '. T o take the last point first, no inscription with her name from our altar has, in fact, survived to us. But much of the architectural framework both of the precinct-wall and of the inner altar has disappeared and we cannot say dogmatically that no such inscription was ever there. And need we, indeed, assume that a monumental altar of this type must have had a label ? As regards the image and the I54 J. M. C. TOYNBEE attribute of Pax-to place her and it in one of the blanks in the Dea Roma panel may well be unsatisfactory. But we now have Hanell's much more plausible suggestion that the three fragmentary foreground figures, one of which is clearly female, at the west end of the southern frieze, at the goal of the imperial procession, are goddesses, of whom one could be Pax and the other two Salus and Concordia (o.c., 88-9, 95-8). Once again, it cannot be proved that Pax did not figure on the monument. Point (2) concerns the coin-types of the Ara Pacis and their relation to what is known of the C a m ~ u Martius s monument. I t is clear from a studv of the numerous remesentations by Roman hie-engravers of buildings that were extant at ;he time when the diis were made that exact, complete, or ' photographic ' numismatic renderings of the monument in question were not to be expected. T h e die-engravers' practice was, in fact, just that ' of simplifying the designs ' (p. 53), of ' telescoping ', and of selecting certain outstanding features. For example, Trajan's Column has, on Trajan's coinage, only six, instead of twenty-three, windings of its spiral relief-band (and these, incidentally, are made to twist in the opposite direction from that in which they do in reality) ; the type with the legend FORVM TRAIANVM shows only the eastern facade, that with the legend BASILICA VLPIA only the eastern f a ~ a d facing e the Forum ; and neither building could be readily identified by us without its label. With these principles in mind we can say that the colonial coin of Tiberius with the legend PAC1 AVG PERP (pl. 5, fig. 18) could be meant to show one side of the precinct-wall of the Campus Martius altar, with the two zones distinguished, but without an attempt to indicate their decoration, and with a very narrow door at the centre. Nero's coin (pl. 6, fig. 5) shows a very accurate, if simplified, version of the ' back ' or eastern side of our monument (and that ' back ', after all, faced the Via Lata and was seen by every passer-by and was therefore scarcely less important than the ' front '). I n the upper zone we see the central seated figures of the Terra Mater and Dea Roma panels, while below them there are extracts from the acanthus-pattern dado. On Domitian's coin (pl. 6, fig. 6) we are shown the steps on the western side of our monument and figure-groups in the upper zone on either side of them ; while to the lower zone on either side the artist appears to have transferred extracts from the very important figure-scenes in the upper zone on the northern and southern sides and to have omitted the acanthus-dado. T h e Neronian and Domitianic types do not absolutely prove that the Campus Martius altar was the Ara Pacis. But both are concerned with Pax and there seems to be a reasonable case for believing that they were intended to represent our altar. And why should not those Emperors have recalled on their coinages an Augustan monument ? Nero, as Dr. Weinstock says, ' liked to stress his connection with Augustus ' (p. 51) ; and Domitian, like Augustus, ' wanted to inaugurate a new era ' (p. 52) of prosperity and peace, such as the founding of the Ara Pacis Augustae had been regarded as heralding. (3) T h e inner altar frieze and its sacrificial animals. T h e Res Gestae passage (12, 2) does not say that the anniversarium sacrijicium ordained to be offered at the Ara Pacis was concerned with Pax alone. Of the larger animals, one at least, as Dr. Weinstock agrees, could have been the heifer of Pax : and would the sex have been indicated if the two animals were heifers ? At any rate, it cankot be proved that a heifer was not intended in the case of either bovid. If, on the other hand, the artist intended to depict fully-developed creatures, he has anyhow been careless in not indicating their sex clearly, whoever the divine recipient of the victims was. Why should we expect him to have shown more care in the case of Pax than in that of any other deity (p. 54) ? T h e sheep and the other large beast could have been meant for deities with whose cult that of Pax was linked : and if the sacrifice to Pax was the culminating rite, her victim would have walked last. On the other extant portion of this frieze, moreover, are the Vestals and the priests who were specifically bidden to perform the sacrifice at the Ara Pacis ; while the third group specified, that of the magistrates, could have figured in the missing portions of the frieze. T h e inner frieze does not prove that the altar is the Ara Pacis : but its contents do not really seem to rule out the theory that it is. (4) The Terra Mater or Italia slab is an unoriginal piece of carving, in the sense that its elements-the central figure and the lateral ' Aurae Velificantes '-were derived from various different sources. These elements certainly appear elsewhere in contexts that have nothing to do with the Ara Pacis. But the composition in which they are combined here most aptly expresses that picture of ' Golden Age ' bounteous Nature and rural prosperity THE ' ARA PACIS AUGUSTAE ' I55 which is the setting of the Pax Augusta in some Augustan poetry (cf. Hanell, o.c., I 16-20). If the similar Carthage slab did come from a dynastic monument (pp. 54-5), that would not prove that its counterpart in Rome would have been unsuitable for an Ara Pacis ; and if the laconic Feriale Ct~manumrecords the dynastic aspect of the new cult of Pax, that does not prove that idyllic notions were excluded from it (p. 49). That people were meant to link Pax and her blessings with the dynasty is clear from an altar from Carthage dedicated to the Gens Augusta, which Dr. Vileinstock quotes and illustrates (p. 55, pl. IX, 3) : in one of its reliefs the symbols of universal, idyllic Peace-globe, cornucopiae, and caduceus-are prominently displayed (cf. Revue des Etudes Latines xxxv111, 1960 (1961), 336). (5) That the southern frieze on the precinct-wall represents some ceremony conducted by Augustus in the presence of members of his family is now agreed by all ; and there can be little doubt as to the identity of the two family-groups rendered at the frieze's western end-the Elder Antonia with her husband, Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, and their son and daughter, to the right, the Younger Antonia, with her husband, the Elder Drusus, and their young son Germanicus, to the left. Few now fail to recognise the velatus at the centre of the scene as Agrippa-despite his shoes (p. 56) ; for the fact that he was entitled since 29 B.C. to wear patrician shoes does not necessarily imply that he must have been always depicted in such footgear at a later date (cf. YDAZ LXXV, 1960, p. 135). T h e same shoes as those of the velatus are worn by the youngish man to the right of Livia, who must be Tiberius, also a patrician, if we discard h'loretti's view that the two wreathed men on either side of the Emperor are the consuls of 13 B.c., Tiberius and Varus, and entertain Hanell's more attractive idea that they are pontiffs assisting at the offering (o.c., 83-4). Opinions may continue to differ as to details. But an Ara Pacis ' constitution ' ceremony on 4th July, 13 B.c., remains the best explanation of the family and priestly gathering that this and the companion northern frieze present us with--a gathering very realistically and intimately shown, but ' ideal ' rather than ' photographic ', including persons who were there by right, if not in actuality, for example, the Flamen Dialis, whose office, while existing, was vacant at the time, and the Elder Drusus, depicted here in military dress, who was abroad on official service until the end of 12 B.C. Such a mingling of the factual and symbolic is standard practice on Roman State-reliefs. Augustus appears to be offering, not a living victim, but incense, to judge by the pose of his right hand and by the fact that a camillus with acerra stands close by (cf. Hanell, o.c., 60-2) ; and Hanell makes the good suggestion that the Emperor himself, not Agrippa, would have deputised in 13 B.C. for the disgraced and banished Pontifex Maximus (o.c., 71-4). (6) How do we know that ' an elaborate altar [of Pax Augusta in Rome] is not to be expected (p. 56) ' ? After all, it was commissioned by the Senate to commemorate the Emperor's return to the capital from his pacifying work in Spain and Gaul and designed to be the scene of an impressive annual sacrifice. Why should we presume that this altar had no further decoration than its inscription and a door in front ? T h e inscribed altars of Pax Augusta at Narbo and Praeneste, which Dr. Weinstock cites and illustrates (pp. 54 ff., figs. I, 2), are local, provincial objects and can hardly be regarded as true analogies of the metropolitan monument. And it is noteworthy that the front of the Praeneste piece bears a swag of fruits slung between bucrania which vividly recalls the swags of fruit that decorate the upper zone on the inner side of the precinct-wall of the Campus Martius altar (cf. Revue des Ztudes Latines XXXVIII,1960 (1961), 336). Part 111 of Dr. Weinstock's paper is concerned with the relief from our altar representing Aeneas' sacrifice of a pig to the Penates. That the veiled, half-draped figure is indeed Aeneas is, as Dr. Weinstock states, proved by the Trojan dress of the man beside him ; and to this may be added the corroborating facts that the shrine of the Penates is perched upon a rocky hill as at Lavinium (cf. Dion. Hal. I, 57, I) and that Aeneas was the well-established legendary prototype of Augustus. No one could fail to note that the designer of our altar has meant us to discover an analogy between the Augustus group in the southern frieze and the Aeneas scene adjacent to it in the southern panel on the west side. I n both the principal figure is veiled and extends his right arm for his offering, on which his gaze is intently set ; both figures are supported by religious and personal attendants, camilli, priests (?), and lictors, in the one case, camilli and the Trojan personage, in the other; and if Hanell's theory of the Isb THE ' ARA PACIS AUGUSTAE ' fragmentary figures at the west end of the south frieze be accepted, both are in the presence of divinities. T h e Ara Pacis was founded not merely for the cult of Peace. I t had also a personal connection with Augustus, being decreed, as he himself tells us, pro reditu meo, in thanksgiving for his home-coming from abroad. T h e processional scene before us would suit very well a thanksgiving-rite on that occasion. At any rate, it shows some very significant ceremony of which the Emperor was the centre ; and it seems to me extremely unlikely that the planners of our altar would have chosen for its legendary counterpart, not the famous, initial ' home-coming ' sacrifice by Aeneas of the sow at the time of his arrival in Italy, but, as Dr. Weinstock holds (pp. 57 f.), some later, secondary sacrifice, of which we have no record in tradition-especially when the scene that balanced the Aeneas panel, that in the north panel on the west side, showed a most familiar legend, the ' home-coming ' of another of Augustus' prototypes, Romulus, to the site of Rome. And do the details of the Aeneas picture on our monument really make untenable the generally accepted interpretation of it ? I t is true that the piglets are not in evidence : but again we do not see them on the medallion of Marcus Aurelius (pl. VI, g), or in any other scene, where the initial sacrifice is certainly represented. T h e sow could hardly have been led to the altar with her offspring still tugging at her udders : their slaughter would presumably have taken place after their mother's. Aeneas, like Augustus, is here thought of as essentially a priest-hence his civilian dress ; and the ' sceptre ' that he holds could be regarded, alternatively, as a priestly baton. As for the adult personage behind him-we do not know for certain that Achates was probably a creation of Virgil's imagination (p. 57) ; and even if we decide not to describe the figure as Achates, what we need in the scene is, not so much ' an important personality ', i.e. Ascanius grown to man's estate (p. 57), as a personal attendant, one of Aeneas' Trojan followers, here featured with a kind of rod of office, the counterpart of the lictors with their fasces who surround Augustus on the southern frieze. If the Campus Martius altar is not the Ara Pacis, what is it ? And what was the occasion of its great imperial cortkge ? Dr. Weinstock cannot say ; but he hints that it might have been the Ara Gentis Iuliae, which in Vespasian's time was sited on the Capitol. Yet we wonder what would have been the point of leaving the Augustan Ara Gentis Iuliae to disintegrate on the Campus Martius and of erecting another altar to the family on another site. Our altar, with its idyllic motives, Terra Mater or Italia slab, acanthus-dado, and swags of fruit, may well ' have served the aims of the dynasty ' (p. 58) and have been at the same time the Ara Pacis, for Pax and her works were an integral part of the Augustan dynastic ideology (cf. again p. 49). And there may be something to be said for Hanell's view that in the well-known passage in Ovid's Fasti I-ipsunt ncs carmen deduxit Pacis a d arum, etc.-are reflected many of the motives of our monument's sculptured decoration (o.c., 120). Dr. Weinstock has most forcibly and usefully reminded us that we have no ineluctable, explicit proof that the Campus Martius Augustan altar is the Ara Pacis Augustae. But he has not, to my mind, succeeded in proving to us ' that it is certainly not the Ara Pacis Augustae ' (p. 58).