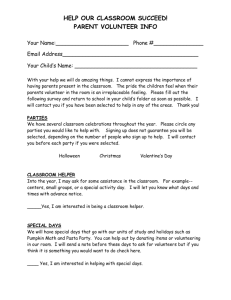

Working with parents in partnership

advertisement