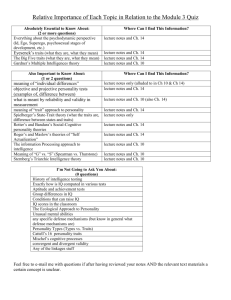

PERSONALITY

advertisement