Chapter 4 Case Study of the Electronics Industry in the Philippines

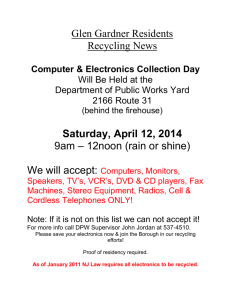

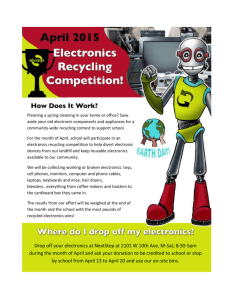

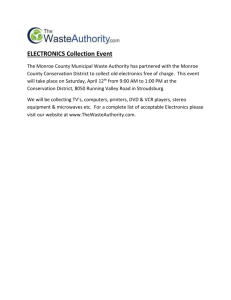

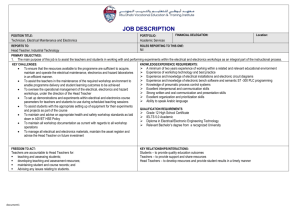

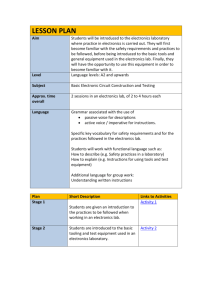

advertisement