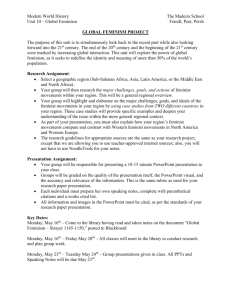

Women in Professional Planning, Architecture and Design – A

advertisement