PDF, 223.7 KB - Queensland Courts

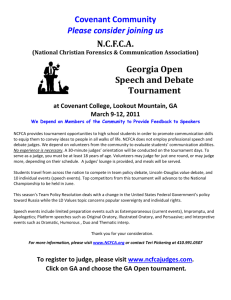

advertisement